It is August 9, 2014. Canfield Drive. Four hours after Michael Brown was shot by Ferguson Police Officer Darren Wilson, the eighteen-year-old's body is finally removed from the scene. A crowd gathers, and they scatter rose petals over the strip of bloody pavement.

Olajuwon Davis, who lives in his mother's apartment just down the street from the Ferguson Police Department, reads the news on his phone. He's on a bus within minutes, heading for the Canfield Green apartments. He's not the only member of the local New Black Panther Party to answer the call and join the outrage building in the crowd.

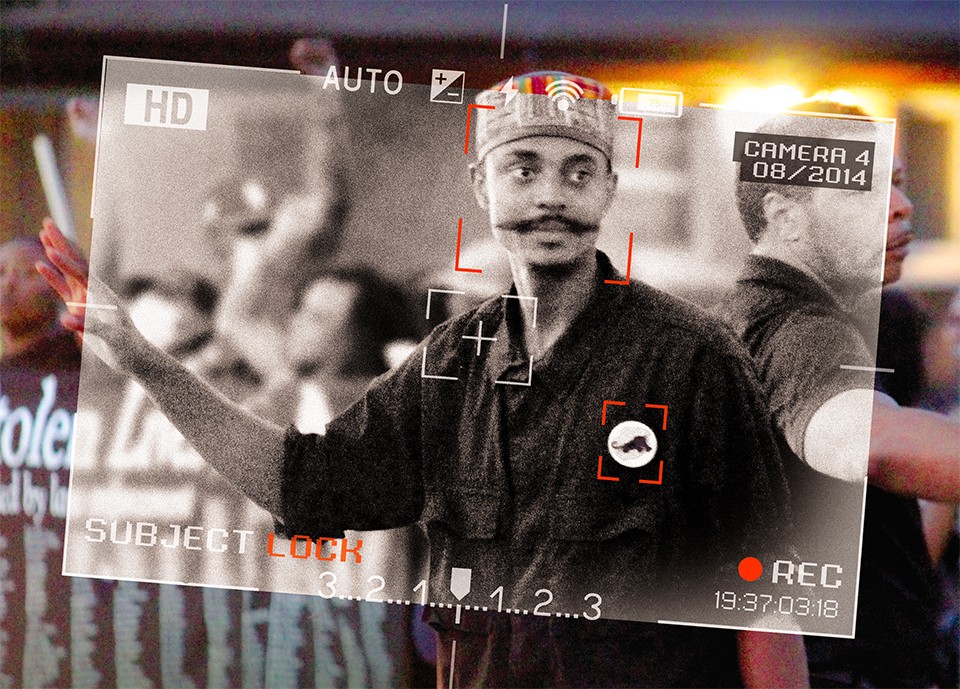

This is where it begins for Davis. As the evening sets on the first day of the Ferguson protests, a bystander films him walking into the middle of the street. Davis addresses the crowd as he paces along Brown's makeshift memorial.

"Ferguson! Ku Klux Klan!" he shouts. "That's who that is!"

That gets some attention, and someone shouts back, "Right on!"

But even among his comrades, Davis is distinctive: His mustache is nearly wider than his face. He wears a black T-shirt with a huge graphic of Malcolm X smoking a cigar. And Davis has a voice, one that carries easily in the evening air and has a confident, chanting rhythm that cuts through the ambient noise of the crowd.

"Forget tired, we fed up!" he shouts. "You tired, you can take a break. When you fed up you ready to hop off the train!"

A young but skillful actor, Davis has training in the art of capturing an audience's attention. But in many ways, he is way out of his depth: Canfield Drive isn't a stage or a film shoot, and it is nothing like the small-scale protests Davis participated in as a teen member of a group of antiviolence theater activists.

He is like so many who will appear in Ferguson: a young activist, invigorated and enraged at Brown's killing, taking to the streets not just in the name of justice for the unarmed Brown, but for a unifying principle behind a new civil rights movement: That black lives matter.

And yet, Davis stands out. In the coming days, as Ferguson becomes a national focus, he wears a red fez and cape, while marching alongside fellow members of the New Black Panther Party. He adopts the title "Minister of Truth and Justice" and uploads a video of himself asking the United Nations for "assistance in helping the indigenous peoples of the world." His outfits and outlook are manifestations of a confusing mixture of ideologies that he's come to believe in.

Along with his membership in the Panthers, he has become intrigued by conspiracy theories. He identifies as an "Aboriginal Moor" and a "sovereign citizen," freed from the legal authority of what he considers an illegitimate government.

Other protesters notice the young radical — and so does the FBI. Agents are already on the lookout for Panthers, and Davis makes himself as conspicuous as possible.

In October 2014, two months into the protests, Davis addresses an audience at a church. He is dressed in all black, including a beret, and looks like he could be standing with the original Black Panthers in California or Chicago in the 1960s. He sounds like it, too, his words urgent and measured with the seriousness of a militant.

"You must have some sense of militancy or strategy in your mind," he tells the crowd. "Because we are all, soon, going to have to deal with this verdict that is about to drop. I reason that it won't be favorable ..."

At this point, the entire region is awaiting a grand jury's decision on the fate of Darren Wilson. But Davis could just as easily be talking about himself. Rather than a triumph of militant strategy, Davis' beliefs will soon carry him away from the protests, away from St. Louis, to his own verdict. And then into prison.

And that is because Davis makes good on his speech about militancy and strategy. In the coming weeks, he works with allies who are not really his allies. He plays a role that he does not realize is a dark fiction. In reality, everything he believes about his life as a militant will turn out to be a lie. He is clueless about it all — until November 21, 2014.

On that day, Davis tries to buy a pipe bomb from the FBI.

Today, Davis lives in a federal prison in Milan, Michigan, more than 500 miles from St. Louis. Reached by phone, the former Black Panther describes his experiences on August 9, 2014, from the bus ride from his mother's apartment in downtown Ferguson to the scene on Canfield Drive.

The scene, he says, "just broke my heart."

"In my mind, I can still see the traces of blood, where they tried to clean it up," he continues. "I was just floored. Then the sadness turned into indignation, just confirming many of the fears I had about living as a young black man in America. Perhaps I would be next. I remember just lashing out, verbally, just expressing my feelings aloud to those who were there."

Davis is scheduled to be released from prison the day after Christmas in 2020. He will have served more than six years in various institutions as a result of his arrest in a 2014 FBI sting operation.

At the time of the bust, law enforcement agencies were under pressure in Ferguson to deal with protests that had drawn worldwide attention. A grand jury was expected any day to deliver its decision, and city and public officials were already preparing for the worst. Police departments ordered more body armor. Office buildings circulated evacuation plans in case of rioting. Schools prepared to close for an entire week. The governor called in the National Guard.

In that atmosphere, the arrests of Davis and a second Black Panther, Brandon Baldwin, on weapons charges provided a useful narrative — that law enforcement wouldn't let the protests explode in violence. News of their capture was quickly leaked to media.

"FBI arrests 2 men for buying explosives near Ferguson," blared a CBS headline.

There was no mention of bombs, only "straw buys" of handguns, in the original charges, but the CBS report cited a "law enforcement source" who described the purchase of explosives. A follow-up in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, citing "sources close to the investigation," added more details, including accusations that the duo had reportedly plotted to detonate a pipe bomb in the observation deck at the top of the Arch.

Davis was the ringleader of the plot, the sources said. The Post-Dispatch described a plan of ambitious violence that included the assassination of Ferguson Police Chief Thomas Jackson and St. Louis County Prosecutor Bob McCulloch.

The implication of the stories was that law enforcement officers had intercepted a terror plot that was already in motion, preventing certain tragedy. After Davis and Baldwin pleaded guilty in June 2015, then-U.S. Attorney Richard Callahan released a statement, saying the FBI operation had "saved lives."

Left unsaid, however, was the full story of how two Black Panthers became targets in a weeks-long FBI sting operation whose every element (including inert bombs) was meticulously arranged and largely funded by two confidential informants posing as protesters.

For Davis, it's also a story of regret and wasted potential: how he started as a college-bound musician and budding actor and wound up convicted in a domestic terrorism case.