DANNY WICENTOWSKI

St. Louis County Sgt. Keith Wildhaber, several hours before a jury awarded him $19 million.

A nearly $20 million jury verdict has hit the St. Louis County Police Department's top brass like a bomb, leaving even Chief Jon Belmar's job in question amid outrage over details revealed at the trial alleging discrimination and workplace retaliation against a gay cop.

In the final two days of the weeklong trial, Sergeant Keith Wildhaber, who filed the lawsuit in 2017, watched as his lawyers cross examined the "white shirts" of the department's command-level staff; it was these top brass who Wildhaber said had repeatedly blocked him from a promotion because he was gay. And not only that: After he filed an employment complaint, Wildhaber was sent on what cops call a "geography lesson" — a retaliatory transfer, which removed him from the south county precinct in Affton to the midnight shift in Jennings, some 25 miles north.

These were the broad strokes of the case, which the department and its defense, led by Assistant County Counselor Mike Hughes, argued was really just an example of a capable-yet-flawed officer frustrated by his inability to land a coveted command-level position.

DOYLE MURPHY

Appointed in 2014, St. Louis County Police Chief Jon Belmar took the stand in Wildhaber's trial.

And if this really is the case that ends Belmar's reign as chief, it will come because of an officer for whom he once had "remarkable fondness." Before becoming chief, Belmar had served as a captain in Affton while Wildhaber was stationed there as an officer. At trial on Thursday, Belmar testified that his regard for Wildhaber as an officer wasn't affected by his knowledge of the cop's sexuality.

"It wasn't a secret," the chief testified. "I didn't hold his sexual orientation against him. I have not, and I did not."

Belmar claimed that the real reason Wildhaber had been repeatedly passed over for a promotion was that he "lacks the discretion of a police lieutenant." It was a conclusion the chief reached, in part, because he suspects Wildhaber tipped off a soon-to-be convicted money launderer whom the FBI was closing in on in 2016. Belmar testified that Wildhaber had later been listed as a "subject" by the FBI's subsequent investigation.

Wildhaber, however, was never disciplined for the incident, and he denied the chief's accusation that he'd played a role in alerting a suspect under watch by the feds. (For his part, Belmar claimed he didn't bring formal discipline against Wildhaber because he didn't want to interfere with the FBI case. He called the situation "a kind of a Catch-22.")

But as the trial progressed into Friday, a web of contradiction began spread across the police narrative. The case became more than an argument over promotion policies, but the credibility of the county's police command itself.

First, there was Belmar, who, as Wildhaber's attorney Russ Riggan argued to the jury, had already given away the entire game: Riggan pointed to a November 2018 deposition, in which Belmar had essentially "confessed" to the charge of retaliation. During the deposition, Belmar had been asked whether Wildhaber’s charges of discrimination made "any impact on his efforts to get promoted to a lieutenant’s position?"

Belmar had answered, "I believe they now have."

At trial, Belmar also acknowledged he found it "upsetting" when Wildhaber filed a lawsuit against the department in 2017. Still, the chief insisted that Wildhaber's inability to land a promotion was simply the result of a department stacked with qualified candidates, and he said even good officers must wait years for their chance to move to the ranks of the "white shirts."

But that's not the message Wildhaber said he got in 2014 when he stopped by Bartolino's restaurant and got into a conversation with its owner, John Saracino, who was then a member of the St. Louis County Board of Police Commissioners. Wildhaber claimed that Saracino tried to give him advice, remarking, according the lawsuit, "The command staff has a problem with your sexuality. If you ever want to see a white shirt, you should tone down your gayness."

In a deposition with Wildhaber's lawyers, Saracino denied ever making the statement or being homophobic — one of several such blanket denials provided by defense witnesses called by the police department, which sought to rebut accusations of an internal culture of intolerance.

The claims and counter-claims piled up. There was Deputy Chief Kenneth Gregory, who denied the account of a former executive assistant who claimed she overheard him citing the Bible to another commander, saying that homosexuality is "an abomination." In his own testimony, Gregory said he never quoted the Bible while on duty.

There was Sergeant Andrea Van Mierlo, who was called to testify on why she had written "gay" next to the name of an officer on a list of candidates applying to the department's Special Response Unit in 2017. (Mierlo denied that she'd made the notation for homophobic reasons.)

Then there was Lieutenant James McWilliams, who flatly denied that Wildhaber had ever come to him to complain about Saracino's comment about Wildhaber needing to "tone down" his gayness. Wildhaber had testified that he had gone to McWilliams for support and relayed the quote, and he claimed the lieutenant responded, "If he had told me to tone down my blackness I would have punched him in the nose." McWilliams said the entire exchange never occurred.

Back and forth. But it was different with Captain Guy Means, who took the stand to similarly deny the claims of one Wildhaber's witnesses. In this case, it was Donna Woodland, who had previously testified that Means had called Wildhaber "fruity" when they were both attending an event in 2015.

As reported by the Post-Dispatch, Woodland testified on the trial's second day that when the subject of Wildhaber came up during the 2015 event, Means had told her "You know about him, right? He’s fruity," and added that Wildhaber was "way too out there with his gayness and he needed to tone it down if he wanted a white shirt."

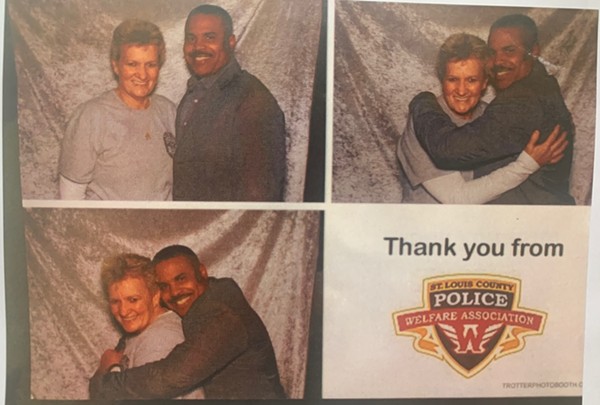

One day after Woodland, Means took the stand. He denied the interaction she described ever took place. Not only did he not remember attending the event, he testified that he wouldn't know Woodland if she was sitting in the jury box in front of him.

That was news to Woodland. On the trial's final day, Wildhaber's attorneys called her back to the stand, and she revealed a three-photo spread of herself and Means, which had been taken in a photobooth during the very 2015 event that Means said he neither remembered or attended.

After three hours of deliberation, the jury returned its verdict. Despite the denials, jurors did not believe Belmar or the top police brass when they insisted there was no homophobia in the department — or that Wildhaber's superiors had transferred Wildhaber to Jennings, far away from his home near Affton, at his own request. (Wildhaber's attorneys had already shown the jury a document, filled out by Wildhaber, which featured a ranking of preferred precincts for transfer. Wildhaber had listed Jennings dead last.)

The total award came close to $20 million. Broken down, the verdict included $11,980,000 million for the charge of discrimination, while the charge of retaliation added $7,990,000.

"If you discriminate you are going to pay a big price," the jury's foreman said after the trial's conclusion, according to the Post-Dispatch. "You can’t defend the indefensible."

There may be even more added to the final toll. In an interview with St. Louis Public Radio on Sunday, County Councilwoman Lisa Clancy called for Belmar's resignation, saying "What was brought to light last week during the Wildhaber trial about the culture within our St. Louis County Police Department, which was then corroborated by the findings of the jury, makes this a very extraordinary situation."

County Executive Sam Page has all but announced a major house-cleaning at the top of the department. In a statement also released Sunday, Page said he would select new members of the Board of Police Commissioners, the five-member civilian board that ultimately has the power to hire and fire a chief. (As of this afternoon, Page has already notified board member Laurie Westfall that she's being replaced, the Post-Dispatch reports.)

"The current police board and chief have served faithfully for years," Page said in the statement released Sunday. "The time for leadership changes has come and change must start at the top."

— County Executive Sam Page (@DrSamPage) October 27, 2019

Although Wildhaber's legal team declined to grant an on-the-record interview, a press release sent Monday afternoon to Riverfront Times called the civil judgement a "historic verdict."

"This has been a long and difficult road for Keith," said the statement attributed to attorneys Sam Moore and Russ Riggan. "Justice was served in this trial, and no client could be more deserving than Keith. The jury acted as the conscience of the community and spoke loud and clear in this verdict."

Follow Danny Wicentowski on Twitter at @D_Towski. E-mail the author at [email protected]