The men head toward the big white van almost as soon as it rolls to a stop in front of Russell Park.

It's just after 3 p.m. on a Tuesday. The park, which stands at the corner of Cabanne Avenue and Goodfellow Boulevard in the West End neighborhood of north St. Louis, consists of a small patch of grass surrounding a large playground in a neighborhood marked by vacant buildings.

Some of the men move with the stiff-legged gait of those who spend their nights sleeping rough, stretched out on concrete or grass.

A tall man nicknamed "Swoop," his hair held together in a series of cascading braids, approaches the van tentatively, his movements halting and cautious as the latest hit of heroin crawls through his veins.

Swoop, 43, says he's been homeless for about nineteen months, and that he uses heroin to self-medicate for chronic depression.

"The depression makes you want to get high," he says. "You have no job. Nobody wants to give you a job because of your appearance and what you're doing."

Occasionally, Swoop earns money from odd jobs in the neighborhood. But when he gets home, it's still the same story, he says.

"We still sitting around," he says. "We get to come back to an abandoned building. We look around, and it's depressing as soon as you walk in the door. So the first thing we do, we got money in our pockets, we get high."

As far as COVID-19, Swoop says he's not worried.

"I'm not really around that many people," he says. "I think God is good. I don't know. I'm just not that concerned about it."

Swoop grabs a brown paper bag from a cardboard box piled high with lunches, then a bottled water from one of the cases left on the sidewalk. He joins the line of other men inching forward to the van.

Standing at the front of the line are Miles Hoffman and Jen Nagel, staff members of the Missouri Network for Opiate Reform and Recovery, or MoNetwork, located at 4022 South Broadway in south St. Louis. MoNetwork owns and operates the van and collects the items it hands out.

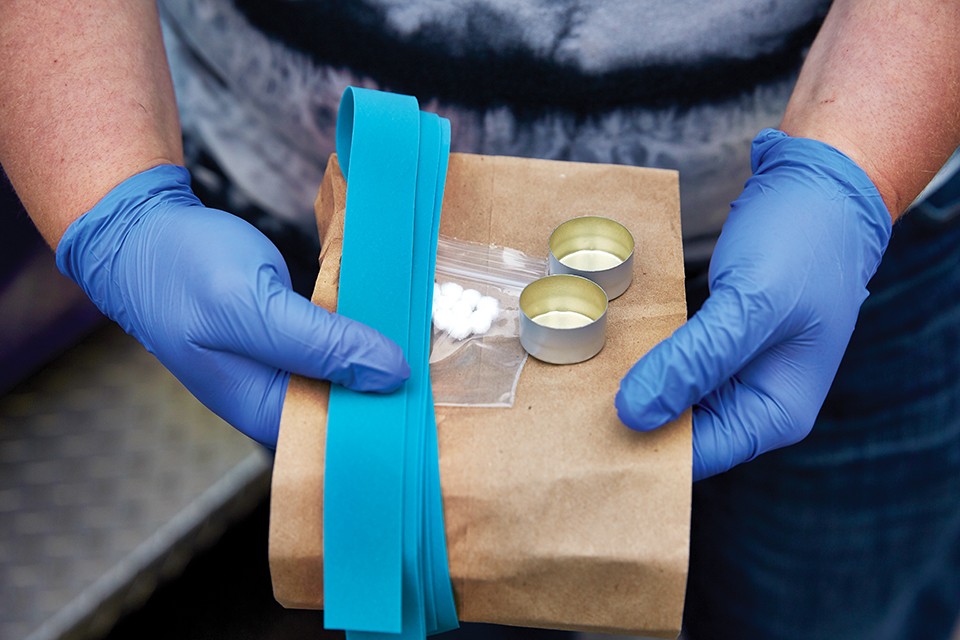

Hoffman and Nagel eagerly engage with the men, smoothly reaching for simple black backpacks, known as Harm Reduction Kits, which they fill with a long list of items calculated to keep their customers alive for another week. Alcohol-soaked swabs. Hypodermic needle disposal kits. Small plastic tubes of Naloxone, also known as Narcan, which can be squirted up the nose to reverse a drug overdose.

In recent months, because of the threat posed by COVID-19, other essentials have been added to the bags: hand sanitizer, disposable gloves, face masks.

Hoffman, himself a recovering opiate user, says he wants to bring more resources to north St. Louis residents struggling with drug dependance and homelessness. Which is why he takes the MoNetwork van to the spots around St. Louis where he knows they're likely to find unhoused people.

About the time he went into recovery a couple years ago, Hoffman says, the market for illegal opiates went from prescription painkillers to much more powerful opiates, such as heroin and fentanyl.

"Things have kind of changed ... the supply had changed, and the drugs had changed, but the people hadn't," Hoffman says. "And being able to give people the supplies they need, like Naloxone, to reverse overdoses for their friends and loved ones, to keep people safe and to keep people out of hospitals and to keep people informed, is something I'm really passionate about."

It's impossible to understand homelessness and drug use in isolation from other big-picture issues, such as access to health care and how people interact with police, Hoffman notes.

"And COVID has made that much clearer," he says. "Now we're seeing these issues are being amplified. So people are saying we need to change things and work within the system."

To Nagel, who is also in recovery, the pandemic's impact on drug abuse is a brutal stew that mixes the results of the United States' war on drugs, the lack of resources for treatment and society's efforts to penalize and moralize away addiction.

"And then you get a worldwide epidemic that's showing glaringly, obviously, that our social structure, our social services, our health services, housing, health care — it's glaringly obvious how disproportionate it is, and how it is not a good system," she says.

The thing of it is, Hoffman says, the system is doing what it's designed to do.

"Which is to keep people in their place," he explains. "And for right now, what we're doing is just trying to directly help people who are most impacted by this."