Rachel Jenness was a young teacher when Kevin Johnson entered her kindergarten class at Westchester Elementary in Kirkwood. The young boy quickly burrowed his way into Jenness’ heart. She recalls that he was a great reader, good at math and had the cutest little smile.

“When you got that smile, you felt like it was a huge accomplishment,” Jenness says.

It was the early 1990s; Jenness was in her mid-twenties. Thirty years later, her education career now behind her, Jenness says she still thinks about Johnson every day, “if not multiple times a day.”

Most of Johnson’s former teachers say the same — because Johnson’s life has taken no ordinary trajectory.

Johnson shot and killed William McEntee in Kirkwood’s historically Black Meacham Park neighborhood on July 5, 2005. McEntee, a Kirkwood sergeant and father of three, died from multiple gunshot wounds after Johnson turned on him in the street, angry about an interaction just hours before that Johnson blamed for his little brother’s seizure and death. After Johnson had already wounded McEntee, he followed him and fired again at point-blank range, an execution-style murder that shook the St. Louis-area for its brutality. Missouri is scheduled to execute Johnson for his crime on November 29.

Seventeen years later, Johnson’s former teachers can’t help looking back. And they won’t sit idle as the state plans to execute the man, now 37, that they remember as a quiet boy who kept to himself.

Jenness is one of many of Johnson’s former teachers who have advocated for the death row inmate since the state Supreme Court scheduled his execution in August.

Jenness herself is not against the death penalty. There are some wicked people, she says, who shouldn’t be around anyone. But not Johnson.

“The gravity of what he went through was ignored,” Jenness says.

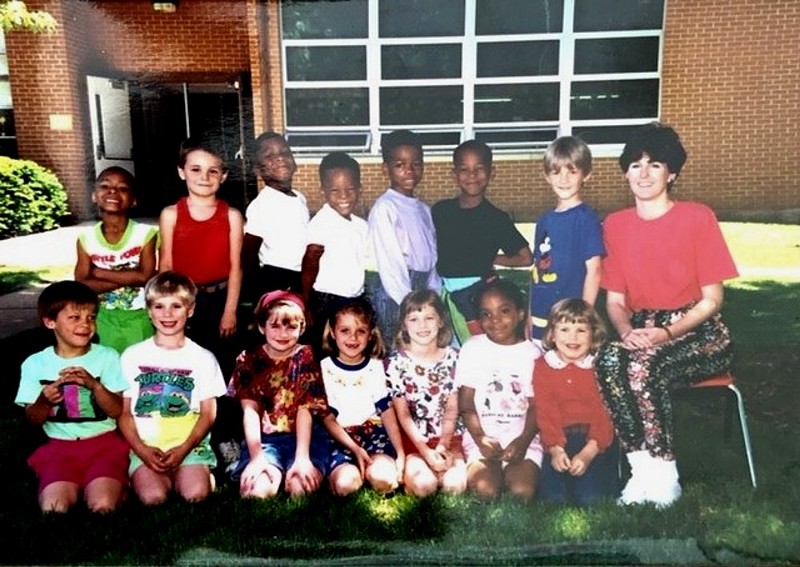

Courtesy Rachel Bee

Rachel Jenness (far right) taught Kevin Johnson (middle, white shirt) in kindergarten and first grade.

In a way, Johnson’s teachers blame themselves for his current predicament. He presented few outward signs of the abuse he suffered at the hands of his aunt as a young child. He didn’t come to school with bruises. Most of the time, he came to school fed and well dressed.

They would only later learn of the difficult childhood he’d endured — and now they can’t help but wonder, should they have done more?

“In a lot of ways, he was failed as a child by the adults in his life,” says Melissa Fuoss, who taught Johnson English in Kirkwood High School’s alternative program.

Johnson’s father was incarcerated for most of his adolescence. His mother lost custody of Johnson and his older brother when Johnson was around four. Johnson has said his mother suffered from a years-long crack addiction, the results of which may have attributed to Johnson’s underdeveloped frontal lobe and a congenital heart defect his brother Bam-Bam was born with.

Johnson then went to live with an aunt, who was emotionally withdrawn and punished him strictly, he says. When Johnson grew older, his aunt kicked him out for not following her rules. After that, Johnson mostly lived in group homes and other family members’ houses.

All told, Johnson entered 19 different foster care placements between ages 13 and 18.

Most of what Fuoss remembers about Johnson was his withdrawn nature. He was quiet. He kept his head down. For one assignment, Johnson wrote a poem about giving his daughter a bath that Fuoss has since searched feverishly for, with no luck.

Jenness and Johnson forged a special bond in her class. They grew so close, that Jenness eventually started considering adopting Johnson. His aunt would come to school to encourage Jenness to spank him, claiming Johnson responded to no other forms of punishment.

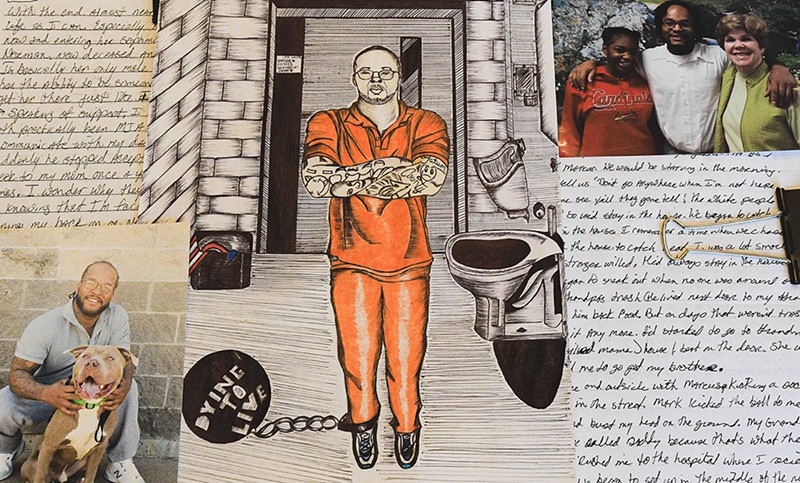

Courtesy Pamela Stanfield

Pamela Stanfield drove Kevin Johnson's daughter, Khorry Ramey, to visit Johnson in prison as she grew up.

Thirty years later, Jenness says she took a special interest in Johnson because no one else did: “He kind of had no one.”

“There’s always going to be regret,” Jenness adds. Regret for not adopting him, regret for not going to prison to visit him and hug him.

Jenness didn’t keep in touch with Johnson after his middle school days. And neither did Pamela Stanfield, former principal of Westchester Elementary School, who didn’t form a relationship with Johnson until after his arrest.

Stanfield cannot remember Johnson ever being sent to her office for reprimands. So when newspapers and TV stations started reporting that Johnson was McEntee’s killer, she was shocked. She thought police had the wrong kid.

That’s when she rekindled her relationship with her former pupil. She visited Johnson in his early days of incarceration and the two have kept regular correspondence since then.

Stanfield’s perception of Johnson didn’t match what people referred to him as — a “cop killer.” He undoubtedly is one, but Stanfield sees much more. Seeing a writer, a dedicated father, she encouraged him to tell his story so people could see him fully. Together, they published two books written by Johnson.

Sarah Lovett

Kevin Johnson wrote hand-written letters to Pamela Stanfield, his elementary school principal, which she kept and arranged into two books.

“Cop Killer” covers his early life; “State Property Dying to Live” details Johnson’s life in prison and reckoning with his actions. Stanfield painstakingly typed each book from emails and hand-written letters from Johnson. Whatever money the books generate goes to Johnson’s 19-year-old daughter, Khorry Ramey.

In an interview with a reporter, Stanfield reads from a passage of “Cop Killer.”

“Guys around here sometimes refer to me as ‘Cop Killer,’ or ‘C.K.’ for short,” Johnson wrote. “I smile and embrace the term on the outside, but on the inside, I say that’s not me. I killed that cop, and when I take my last breath on that gurney, as dozens of spectators watch, that’s what they will see. A cop killer.”

Stanfield shakes her head at this passage, her right index finger tracing KJ’s words as she reads them aloud to a reporter.

“He’s not just a cop killer,” she says. “He’s so much more.”

READ MORE: Kevin Johnson Has Grappled With His Guilt for 17 Years — But He Doesn't Want to Die