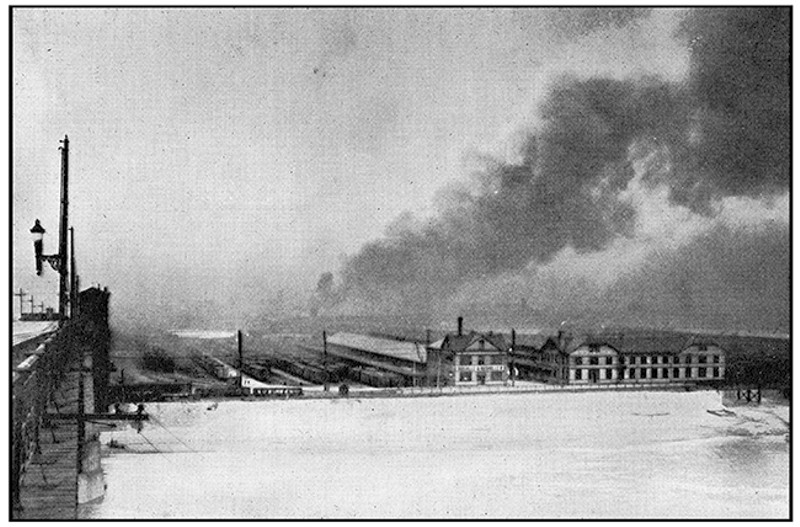

It was the summer of 1917, a Monday in July, and smoke billowed thick and charcoal dark above East St. Louis. The city was burning. Across the Mississippi River, refugees who had fled to St. Louis watched the flames overtake the horizon. The distant crackle of gunfire carried through the night.

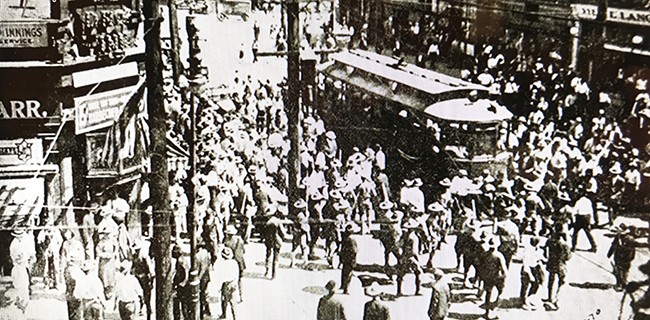

What would enter the historical canon as the "East St. Louis race riot" amounted to a two-day nightmare for the city's black residents. Primed by months of racist fear-mongering from union leaders and newspapers, roving mobs of armed whites — men and women, young and old — took to the streets on the evening of July 2, 1917. They tore through the Illinois city, wrenching black men and women from streetcars and setting fire to black-owned homes.

Carnage wracked the city. Blacks were indiscriminately shot and beaten with paving stones; others were lynched from telephone poles or left to bleed out in the street. The butchery did not cease until a show of force by Illinois National Guardsmen on July 3. Even then, sporadic arsons and beatings continued into the coming weeks.

The attacks began with a case of mistaken identity — and a thirst for revenge. Interviews conducted by the St. Louis Argus (and echoed in a later congressional inquiry) spoke of a weeks-long wave of terror leading up to the deadly evening where mass violence ignited: "Negroes...waylaid and beaten by white thugs, without provocation, daily."

The match was struck the night of July 1. It was a day featuring multiple reports of beatings — one black man was said to have shot his attackers and escaped, but the evening would bring a drive-by shooting targeting black residents. The Argus reported: "An automobile traversed a portion of the Colored district, speeding at a rapid rate and its occupants shooting into the homes of the residents."

In response, armed blacks mobilized themselves into a defense force. But when they fired back, they struck the wrong target.

Around midnight, two plain-clothed detectives driving into a black neighborhood were mistaken for the shooters. In a moment of confusion, a crowd of armed black men, roused by the ringing of a church bell calling residents to defend their neighborhood, fired on the officers, killing both.

Less than 24 hours later, the East St. Louis police department turned a blind eye as white rioters called for a bloody solution to what one union leader had previously called "the influx of undesirable negroes."

See also: First-Hand Accounts Show the Horror of East Louis' 1917 Race Riot

Samuel Kennedy was barely seven years old when the mob came to his family's home on Piggot Avenue, near the south end of town. Night had already fallen on July 2.

The Kennedy home was little more than a shack, and as the rioters blasted bullets through the windows and set fire to the walls, little Samuel followed his mother and a handful of siblings out a side door.

The rioters had blocked a nearby bridge. (According to one witness, members of the mob had decapitated a woman and left her body and head lying on opposite sides of the bridge's entrance ramp — a warning to blacks seeking escape.) So Samuel Kennedy followed his mother across the railroad tracks. On the way, the remaining family members gathered driftwood and salvaged bits of the burned houses, anything wooden and somewhat stable. They carried the items to the river's edge.

The raft, when it was ready, was a shoddy but seaworthy vessel. It took them hours of paddling to finally wobble the improvised lifeboat across the Mississippi. Safe on the Missouri side, Samuel looked back at the glowing city. The screams of its residents drifted over the water. It was a sound he'd never forget.

Even in wartime (the U.S. had entered World War I in April), news of the massacre dominated every local paper, and what reporters described was nothing less than mass murder. The massacre's victims, wrote St. Louis Post-Dispatch reporter Carlos Hurd in one of the first published eyewitness accounts, had been issued a "death warrant" based only on the color of their skin.

"I saw man after man," Hurd recounted, "with hands raised, pleading for his life, surrounded by groups of men — men who had never seen him before and knew nothing about him except that he was black — and saw them administer the historic sentence of intolerance, death by stoning."

The mob-driven chaos raged until the afternoon of July 3. Later attempts to calculate the death toll were complicated by widespread dumping and burning of bodies, but most historians estimate that between 40 and 200 people perished and hundreds more were injured. The white mobs further destroyed hundreds of black homes, as well as businesses and industries perceived to have employed the "undesirable negroes." Around 7,000 black residents fled to St. Louis. Many stayed there permanently, choosing to forsake the city which had so viciously cast them out.

There were no terms for this sort of catastrophe. What does it mean when a mother and child are shot, one after the other, and then thrown into a burning house to die, owing only to the color of their skin? The words for "genocide" and "ethnic cleansing" were decades from invention. Some historians would eventually borrow the word "pogrom," used for the wave of ethnic killings that targeted Jews in Russia in the 1880s.

There is another word to describe what happened in East St. Louis in 1917, and it is the term Samuel Kennedy used when he finally told his own sons what he had witnessed that terrible summer.

"The story that was passed to us by our father, by our uncle, by our aunts and cousins who were all survivors — they called it 'the race war,'" recalls Terry Kennedy, a St. Louis city alderman like his father. Samuel Kennedy represented the city's 18th ward from 1967 until his death in 1988.

Terry Kennedy pointedly avoids referring to a "race riot."

"It wasn't a riot for them," he says of survivors like his father. "It was a fight for their very life and existence."