Mike James never knew his father.

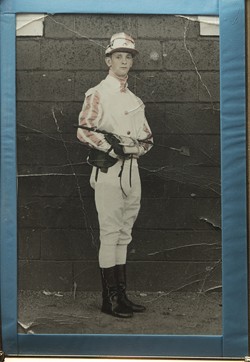

C.H. "Rusty" James, a thoroughbred horse jockey, died in 1962 after an accident during a race in Decatur, Illinois. Mike was just nineteen months old at the time.

The younger James chuckles at the irony that he himself has spent his entire adult life — nearly 40 years — as a thoroughbred jockey, in spite of the way his father died. He doubts his father would have wanted him to follow the same career path.

"He would have tried to discourage me from doing it, because it's such a rough life. It's such a rough profession," James says. "It's hard, it's dangerous, you know. You really don't want your children to grow up and do something that you do that is so dangerous."

James, 56, is a survivor.

After riding in more than 12,000 races — winning 1,200, and counting — James has endured a broken collarbone, broken pelvis, broken right femur and more concussions than he can remember. Married five times, the father of five is mulling whether this year at the nearby Fairmount Park racetrack will be his last.

James admits it's getting harder to stay in the business, in large part because of the economic struggles facing the industry. At Fairmount, the number of race days has dwindled to only two per week, purse sizes remain small relative to the bigger tracks around Chicago, and the proliferation of legalized gambling in Illinois and Missouri — as well as countless other entertainment options — has bitten deeply into the horse racing industry's profits and market share.

There is also the matter of age. James is the oldest jockey at Fairmount, and one of the oldest in a grueling profession in which most participants quit before they turn 30. There are jockeys out there older than James — the legendary Cowboy Jones raced into his early 70s — but they are few.

James has already quit horse racing three times to make his living as a long-haul truck driver, but the sport keeps calling him back. "Riding a race is a feeling you can't really describe," he says. "It's you and the horse and the other people around you. It's not for the faint-hearted, believe me."

At the end of the current season, James says he will take stock and decide if it's the right time to hang it up and move on to something else. Maybe start all over again, this time as a horse trainer.

"My body is telling me it's time. My mind and my heart are telling me it's not," he says. "It's kind of a catch-22. I'm trying to face reality and it's hard to do. I would like to do it as long as I possibly can."

James stands in the kitchen of the tidy Collinsville house that he shares with his mother Nancy. He wears a sleeveless T-shirt. In the shirt's front pocket: a pack of L&M cigarettes.

James admits smoking is bad for him, and that family members hassle him for it, but the habit has its purposes. He nods to the refrigerator a few feet away.

"If I quit smoking my head would be in there 24/7," he says.

Among professional athletes, jockeys are the worst-paid and suffer the worst injuries.

The winning horse's owners get 60 percent of the purse, while the winning jockey gets just 10 percent. That means the winning jockey of a race with a purse worth, say, $5,000 gets $500.

And not everyone wins, of course. The horse owners finishing second and third get 20 and 10 percent of the purse, respectively, with those winnings further cut by fees usually paid to agents and equipment valets. This leaves precious little for the jockeys. At Fairmount, a second-place finish earns a jockey just $70. Third place scores $60. Everyone below that takes home $55.

In 2012, Ramon Dominguez was America's top-earning jockey. He rode horses that won pursues totaling more than $25 million, earning him an estimated $2 million. However, the great majority of America's 1,300 jockeys earn between $35,000 and $40,000 per year. Some apprentice jockeys at smaller tracks earn so few prize dollars they must take second jobs to support themselves, according to CNN Money.

The relatively low pay for most jockeys is one thing, but the toll on the body can be even worse.

The trick to being a successful horse jockey is to be both light and strong. Even though there is a premium on lightness, jockeys know that weighing too little will undercut the tremendous strength needed to control the enormously muscled, often temperamental and unpredictable horses they are riding.

But maintaining that strength while remaining light is a tightrope act for most jockeys, a job demand that requires tremendous self-discipline and knowledge of their own bodies.

While there is no real maximum weight for jockeys, most try to stay under 116 pounds. To keep their weight down, especially as they get older, jockeys resort to a variety of tricks and techniques.

They smoke cigarettes. They spend hours in saunas or run endless miles swaddled in towels and rubber sweatsuits. They follow extremely low-calorie diets in which breakfast might consist of a single egg, lunch a salad and dinner small portions of broiled chicken and rice.

When jockey Victor Santiago takes his wife and kids out for ice cream, he sticks with a bottle of water.

"You got to be tough on that part," Santiago says, adding, "I don't mind doing it."

Alcohol is something jockeys almost never touch, which can make socializing with non-jockey friends difficult, says apprentice jockey Brooke Stillion, who lives off a diet consisting of "a lot of salads and hard-boiled eggs."