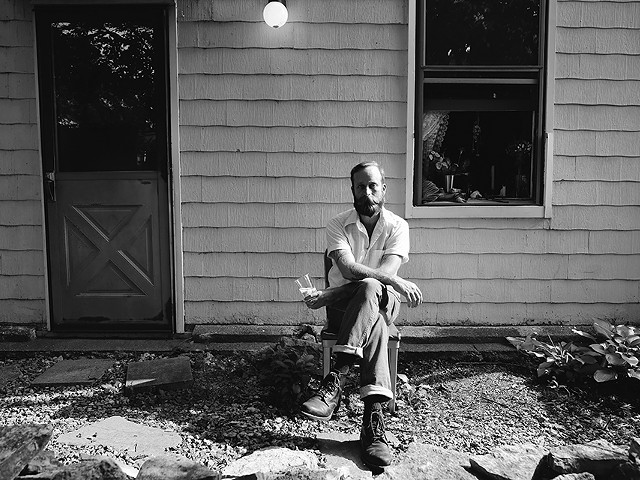

SARA BANNOURA

Rafe Williams' album was released by 800 Pound Gorilla Records, known for its work with Marc Maron and Pete Holmes.

With St. Louis comedian Rafe Williams, what you see is not always what you get. As a matter of fact, that distinction — the gap between the first impressions that people make on each other and the truth — lies at the heart of the performer’s work. As he puts it, “No one is two-dimensional. Everyone contains multitudes.” And Williams is the ultimate example of this philosophy.

In person, Williams is tall and stocky with rough-hewn features, a prototypical heterosexual white guy from the midwest. He jokes that strangers frequently mistake him for a cop — a claim bolstered by the fact that he dresses in the dark, nondescript clothes of an undercover officer.

“I’m a Democrat trapped in a Republican body,” he laughs. “So I do feel like a man without a country sometimes.”

And at first glance, he indeed comes across as a lost member of the Blue Collar Comedy Tour — his standup routines punctuated by colloquialisms like “ain’t” and “fidna,” as well as references to rural pastimes like “trying to finish the golf tee game at Cracker Barrel.” But true to form, he also drops words like “approbation” and “mesomorphic” into casual conversation and co-hosts a podcast called The Other Side of the Tracks that explores topics like “the Overview Effect and how it applies to the future of human consciousness in tumultuous times.”

Even the story of Williams’s life, which is epic and well-documented, changes depending on how an individual looks at it. Framed one way, he is completely average, a self-described poor kid from southern Illinois — or northern Kentucky, as he calls it — who was raised by a domineering father. He adapted by taking on the role of class clown in school, got his former girlfriend pregnant at nineteen, left college and eventually became the stereotypical alcoholic bartender.

“I was like those state fair drawings with the big head and the little body on a surfboard with beer cans everywhere,” he says.

But viewed from a different angle, Williams was a bright student who excelled at sports, served in the military, helped raise a child, obtained a master’s degree in healthcare administration and launched a successful standup career at the age of 33 — all while battling addiction and crippling stage fright. Far from the down-home everyman that Williams plays on stage, he is actually one of the most complicated figures in today’s society: a white, millennial male who achieved the American Dream without an elite education, sizable inheritance or famous last name.

“We are not in demand right now, which is good. It’s good for the greater good, not great for me,” he laughs.

These contradictions come together with hilarious effect on Young Grandpa, the debut album that the comedian released in January. The hour-long set, produced by 800 Pound Gorilla (the label behind artists like Marc Maron and Pete Holmes), was recorded at the Improv Shop in St. Louis and centers around Williams exploring his identity as a 40-year-old grandfather. “I think every joke has to have a nugget of truth in it,” he says. “You can use wild exaggeration for emphasis. But if there isn’t a nugget of truth in there, the audience doesn’t relate to you.”

The charm of Williams as a comic is that his strongest material is delivered at his own expense — or that of his peers — in ways that both confirm and subvert “bro” stereotypes. As a result, Young Grandpa is guaranteed to make both liberal and conservative listeners uncomfortable.

“Comedy’s weird,” he says. “It starts off adversarial, but it’s combative and collaborative at the same time.”

It doesn’t always work. Williams’s penchant for impersonating black men, including the rap parody on “Animal Humane Committee,” feels more like punching down than finding compromise. But those are rare missteps on an album that culminates in a wonderfully unhinged, virtuosic bit as impressive as anything on Netflix.

An extended conversation with the universe, “Love, Sacrifice and Ren Faires” opens with a sharp description of the title activity. “A Renaissance Faire,” Williams explains, “is when a whole bunch of white people go out in the middle of the forest and they dress up like different eras of history that only a white person would be comfortable living in.” He considers the larger joke, which extols the virtues of patience and gratitude, one of his favorites.

“It’s hard to stay on a single subject for ten to fifteen minutes,” he notes. “Not a lot of comedians can do it.”

In addition to touring regularly, Williams also belongs to several teams and teaches classes at the Improv Shop; he creates advertising content for St. Louis brands like Imo’s and Purina; and he appears on numerous podcasts and radio shows across the region.

“To me, success is being able to support myself with comedy,” he laughs. “But when I get there, I may not say that.”

The odds that he settles for just paying the bills seem low, given that he made enough as a performer last year to quit his day job and it only fueled his ambitions.

And now, thanks to this combination of hard work and perseverance, Williams is poised to break into the mainstream. On March 6, he brought his trademark midwestern humor to television as part of the series Stand Up Nashville! on Circle — a new country music and lifestyle network from the creators of CMT. If fans missed the initial broadcast, fret not: It is scheduled to start streaming on the Circle website in May. And over the next few months, Williams is pitching two original properties — a sitcom based on Young Grandpa and an educational reality show — to a number of interested studios.

In St. Louis, Williams is probably best known for his turn as Ronnie Jenkins-Trump — the President’s fictitious half-brother — on STL Up Late, the former KMOV sketch show. The character was inspired by comedians like Sacha Baron Cohen and Stephen Colbert, who satirize conservatives in ways that appeal to viewers across the political spectrum.

“Love and empathy are a much better place to come from,” he suggests. “If you’re really trying to say something to get an audience to budge, you can’t be preachy and you can’t be hateful.”

Williams was actually performing as Jenkins-Trump on election night in 2016. He was supposed to play the villain, complaining about the rigged system and unfair process as the results came in. Of course, the evening took an unexpected turn, and as members of the crowd started to weep, he changed tactics immediately — consoling his fellow liberals as much as circumstances allowed.

It’s just one danger of practicing radical empathy in an increasingly polarized nation.

“I still have white trash tendencies that I grapple with,” he admits. “But I have one foot in progressive dissidence and the other in my midwestern roots. And the truth is always in the middle.”