Life goes inexorably, chillingly on. The Up series, Michael Apted's famous calendrical march, presses on now into its eighth episode, with the same dozen or so Brits from across the class spectrum once again interviewed about their lives after the usual seven-year interval. Suddenly, all of these pitiable souls, subjected for their entire lives to Apted's nagging cameras, are a few creaky strides away from retirement age. It's cinema that in its very form inspires us to wonder, as we do about our own lives, Where in hell did the time go? Minute by minute, Apted's films can be orthodox, middlebrow affairs, but because of the unique accumulation of time — the series is the only film project to have transpired sequentially over a 50-year span and counting — the movies stand as something like an unpleasant monument to our own ephemerality.

At 56, several of the Uppers have regretted their obligation, and this time, they simply stop sharing much. That's understandable — put yourself in their shoes. There's no underestimating the degree to which the Up project is now about itself, about a BBC filmmaker perpetually hovering over and meddling in the lives of average citizens, many of whom today might be reality television's only completely disgruntled participants. So be it; their lives are ours now.

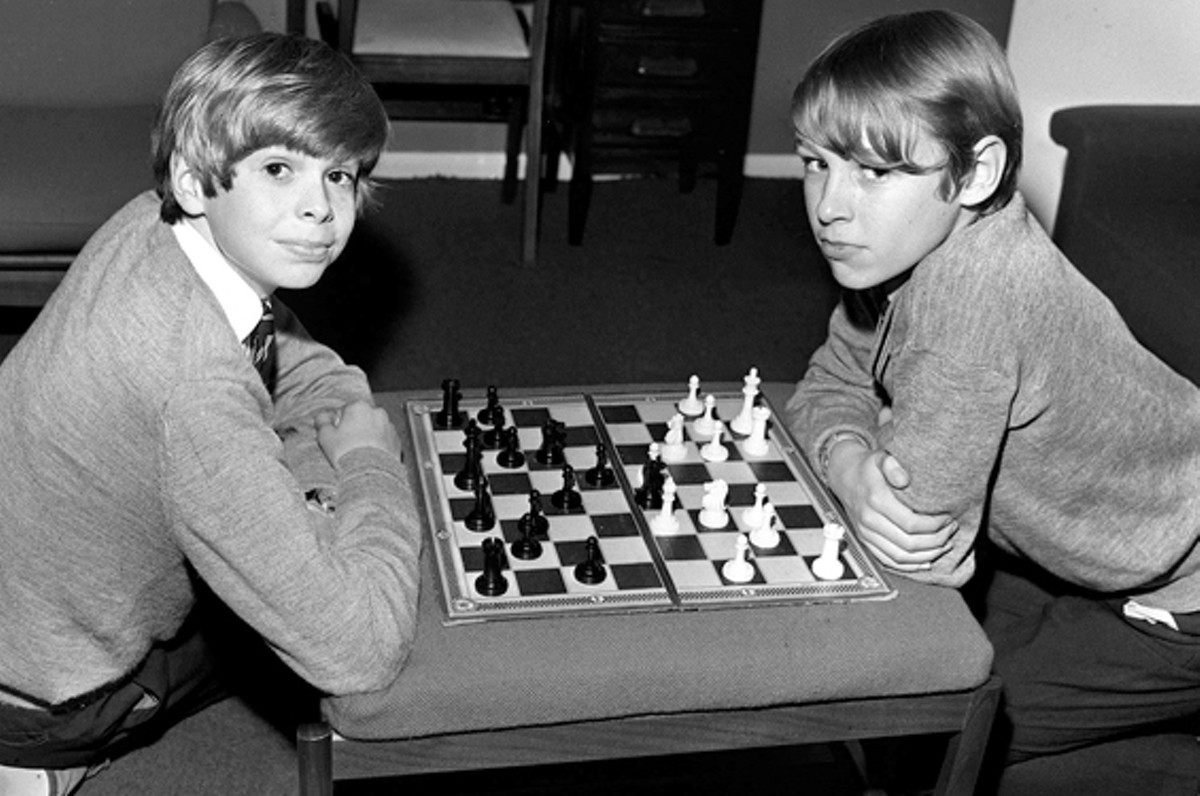

Although the inequity of the class structure in Great Britain was an unavoidable subtext from the start, by the time 28 Up rolled around, the devastation of age became the primary drama. We see the harrowing dynamic laid out like a timeline, and the effect of 56 years on a little girl's dimpled visage can be brutal to watch. As Apted cuts between 1964's brace of cherubic second-graders and the adults they have unceremoniously become since, each subject transforms from a fresh schoolkid sprout to a heap of dead wood, plagued by obesity, alcohol, emotional wear, illness and bad English dentistry. These most recent two sections of Apted's mystery train could be the grimmest and most haunting of horror films for under-30 viewers who still think they're immortal.

As pop anthropology, the series is unchallenged. The thorough sense you get of English life's exigencies, barriers, assumptions and mundanities is not obtainable any other way except by living there yourself. But the Jesuit maxim that started the whole megillah — "Give me the child until he is seven, and I will show you the man" — is shredded by reality. Only a few of the wealthy and privileged subjects, like Andrew the barrister, are remotely like the impish, loquacious children they were in 7 Up. For everyone else, life was a series of half-assed experiments, and their workaday outcomes largely the product of luck. As a social portrait, the series remains largely a matter of working-class dreams meagerly met or lofty dreams dashed.

So Neil is still semi-destitute in the north, Suzy is still a happy homemaker sick of Apted's intrusions, Tony is still a cabbie, Jackie still suffers from rheumatoid arthritis, Peter is back after a 28-year hiatus because, he says, he has a band he'd like to publicize. Lynn the librarian has been made redundant, though Bruce the math teacher eyes a comfortable retirement. And so on. (There are still plenty of hand-holding beach walks.) Any nudge toward political statement doesn't survive the films' real-time historical reach — life took over long ago, in all of its banality, privacy, employment struggles, and divorce pains.

By now, grandchildren are ever-present, and stasis has set in. Apted's entire project is awesome in scale but subject to inevitable diminishing returns: These Brits are naturally cagier and less interesting now that most of their lives' major changes are behind them, and the effort to pack in a full half-century of history leaves us less time to linger in any given story. But that's something like living a life, too: the inability to find perspective, the visceral rushing motion toward old age. Like the average life Apted hoped to peg, the Up series has had an arc — dramatically, 35 Up was its acme, startling in its juxtaposition between childhood innocence and the tolls of a hard midlife that had just begun to throw up challenges. Ever since, we've been lost in the wind-down; at 56, menopausal struggles grind quietly on. From here on out, we can look forward only to autumnal days and death. Happy New Year.