On a random weekend some years ago, I rolled into a bar in Dupo, Illinois. It was named after the owner, who, it appeared, was the lady sitting in a little recessed nook. She was watching the local news from her chair, volume turned way up. She served me a beer, but when I tried to ask a few questions, they went nowhere. She'd seen and done enough in that job.

It can happen to the best bartenders, whether their name is on the front door or not. The stresses can be nuts, the social tension a real thing.

I would know. I visited that little bar in Dupo as a journalist, back when I wrote a nightlife column, but four years ago, I myself became a part-time bartender. For me, a ticket off the adjunct-teaching train came through the co-purchase of the Tick Tock Tavern, which had been sitting empty for nineteen years in Tower Grove East. The previous owner, Charlotte, was a firecracker, running an "old-man bar" in a period when such spots dotted south St. Louis. When she was done, she was done for real, locking the front door and living upstairs for another nineteen years, bottles of Galliano and Pepe Lopez tequila opened and aging (poorly) on the backbar.

I didn't start bartending right after my partners and I reopened the Tick Tock, but in recent years I've gotten into aspects of the trade. I remain a cap-popper and draft-puller at heart. There is no bartender's apron in my wardrobe, and ingredient lists above four cause my robot brain to overheat.

Even so, it remains a difficult gig. A few months back, my new doctor was manipulating my aching left knee, moving it hither and yon while looking for clues. In between awkward bursts of movement, I heard questions and answered in the negative: No, I hadn't suffered any trauma in the knee, and nothing had knocked into it, banged off of it or otherwise made contact. The pain, I assured him, had come from a three-day stretch of bartending.

Even for those of us working on rubber mats, the hours of standing, interspersed with quick bursts of movement, can take a toll on your sticks. For some of us, it's ankle pain, for others, the knee — and so on, with bartending aches and pains slithering north all the way up to your neck and shoulders. The older you get, the greater the chance that a body part that's agreed with you forever suddenly decides to let itself be known. For me, a bum knee was a new entry to the catalog of afflictions. It would take a very effective cortisone shot to make life immeasurably better.

But it's not only the wear and tear on the body. Talking to a quartet of St. Louis bartenders who've been in the game for twenty or more years, I found myself thinking about what makes the game difficult today.

These four veterans have made everything from Brandy Alexanders to liquid marijuana, rusty nails to green-tea shots. Yet the people they've served have changed as much as the drinks they drink. Back in the day, the challenge might have been getting someone to try something new. Today, it's getting a barfly to put their phone down and talk to someone new.

They've been there and done that, but they haven't given up. They could teach that lady in Dupo a thing or two. Me as well.

The Artist

Red Keel

Venice Cafe

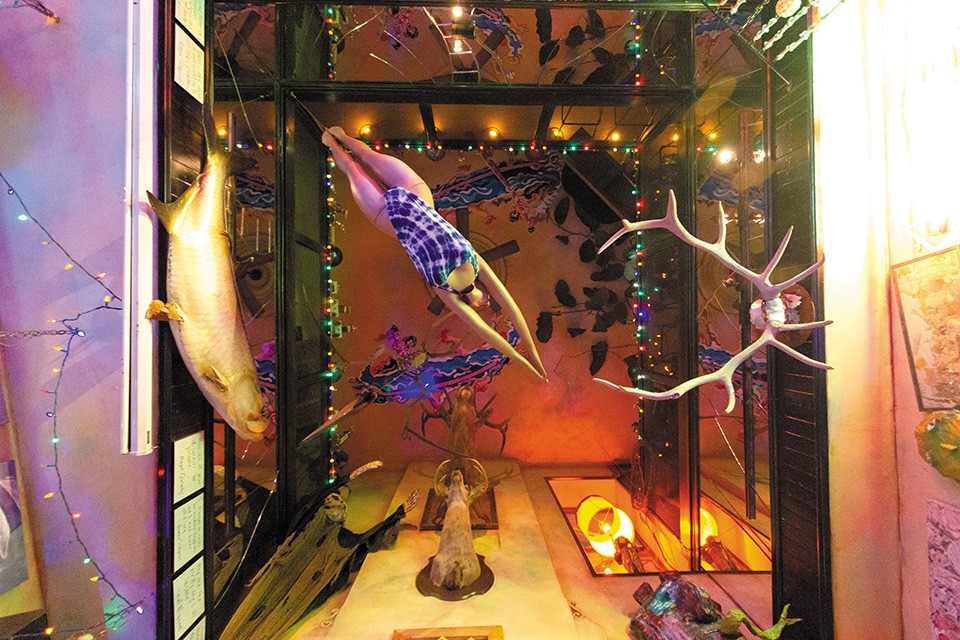

Staffers at bars with a lot of stuff on the walls know the drill. You're going to answer the same query a dozen times, a hundred times, a thousand times. At O'Connell's, the questions are going to revolve around the antiques, the images of balloons and boxers, the chandeliers. At Yaqui's, the painting of Josephine Baker, hung next to a series of painted volleyballs, will draw inquiries. At the Tick Tock Tavern, the owls and clocks bring questions on a daily basis. At Venice Cafe, the questions are about ... everything.

It's almost as if a cheat sheet would help.

Voila! Red Keel has answered questions about the colorful Benton Park bar more times than she can count, and now she's now able to pull out a single sheet piece of paper, wrapped in plastic. It was written by bar manager Chad P. Taylor and owner Jeff Lockheed. The basics of the place are all here, giving a sense of the artistic landmark's beginnings as a coffeehouse with digressions into its name, its ownership and the artists who help make the place what it is.

That group includes Keel, who worked on many of the mosaic tile murals at the Venice. For a while, she pursued art full time, but the cash money always helps and so she's been back at the Venice off and on for twenty years. She works alongside the club's long-running Monday night open mic, as well as a Saturday afternoon shift that alternates live bands playing classic country in one case with reggae in the other.

"Once you meet me, you know me," she says. "It's not hard, though you might see me in public and I'll be confused without context. Give me some context! 'Is it from mosaics, the bar business? How do I know you? I'm Red.' That's all I've got."

In her colorful blazers, her curly hair pulled back in a trademark style, Keel says, "It's about being large and being on stage. You're bigger than life. You can't really do that in most areas of your life. It's fun to come in, get that energy out of yourself, make good friends and get a family going here."

She figures that about 15 to 20 percent of the Saturday happy-hour crowd are regulars, a number that rises to a 40 percent rate on Mondays. She knows their quirks and habits and conversational go-tos. The new folks, well, she'll prompt them for the same.

That portion of the job has changed immensely since she began her work at Patrick's Westport Grill in the 1980s.

"One of the biggest differences is the cellphone, and that means people aren't here to meet each other," she says. "People are very into their phones, they're very cliquey and not going to interact, which I think is a shame. It's very closed-minded. If you sit down, shut off your phone and interact with humanity! These are people who live near where you live. There are far less preconceived notions and biases when we get to know the real human inside. We all just want to be acknowledged. So I say 'hello' to everyone and anyone leaving gets a 'goodbye.' I'll even holler that over the band.

"I want them to know," she continues, "that I appreciate you for giving me money and hanging out here. You'll get a smile and sometimes that can make a night; that I acknowledge you and you acknowledge me. It makes you feel special."

So, go ahead, ask her a question, any question. She's Red. She won't mind.