Every year on Veterans Day, Karen Harty would think about her oldest son.

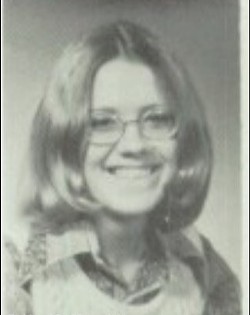

It was not because he was in the military, although he could have been. She had no way to know. Harty had been just sixteen years old in 1974 when the baby was born at the old St. Louis County Hospital. She was only allowed to hold him for a moment or two before he was hustled away, leaving her alone to wonder what was next for the little boy.

She had made the decision to put him up for adoption, but then what? Would his new parents be good to him? Would he have a nice life? The instant he disappeared from her sight, he became a mystery.

At the time, Missouri laws governing adoptions presumed this was best. Better to make a clean break and let everyone move on with their lives. The state recorded the spare details on the birth certificate — date, time, Harty's name and address in Florissant — and then sealed the document with the intention that no one would ever see it again.

But Harty always wondered what happened to the boy. Before her son was born, she and the child's father spent long hours talking about whether they could raise him. Her boyfriend wanted to try. He hoped to talk Harty into getting married, and he joined the Army at seventeen to support them.

But Harty's parents could offer little help because they were taking care of her sister who had Down syndrome. They rejected the idea of a teen wedding in favor of adoption. She ultimately decided they were right, but it broke her heart.

"I just felt like at my age, it was the right thing to do," Harty, now 60, says. "The best thing to do for him, not necessarily for me, but for him."

And so on Veterans Day of 1974, Harty's mother drove her to the hospital, where the teen gave birth to a healthy little boy and handed him away. She has thought about him ever since, ticking off the birthdays as he turned 18, then 30, then 40. Was he happy? Did he have a nice life?

Harty and the boy's father never saw each other again. She got married and divorced and married again. She had three more kids, and raised them. She is a grandmother now. It has been a good life, but she could not forget her firstborn. Each Veterans Day, her husband of 30 years, Dan, would see the sadness in her face and ask, "Are you thinking about him?" Invariably, she was.

All she had of the boy were those few moments after he was born. Forty-four years later, she still remembers them vividly. She recalls kissing the top of his little forehead. Just before he was taken away, she whispered in his ear: "I hope you find me one day."

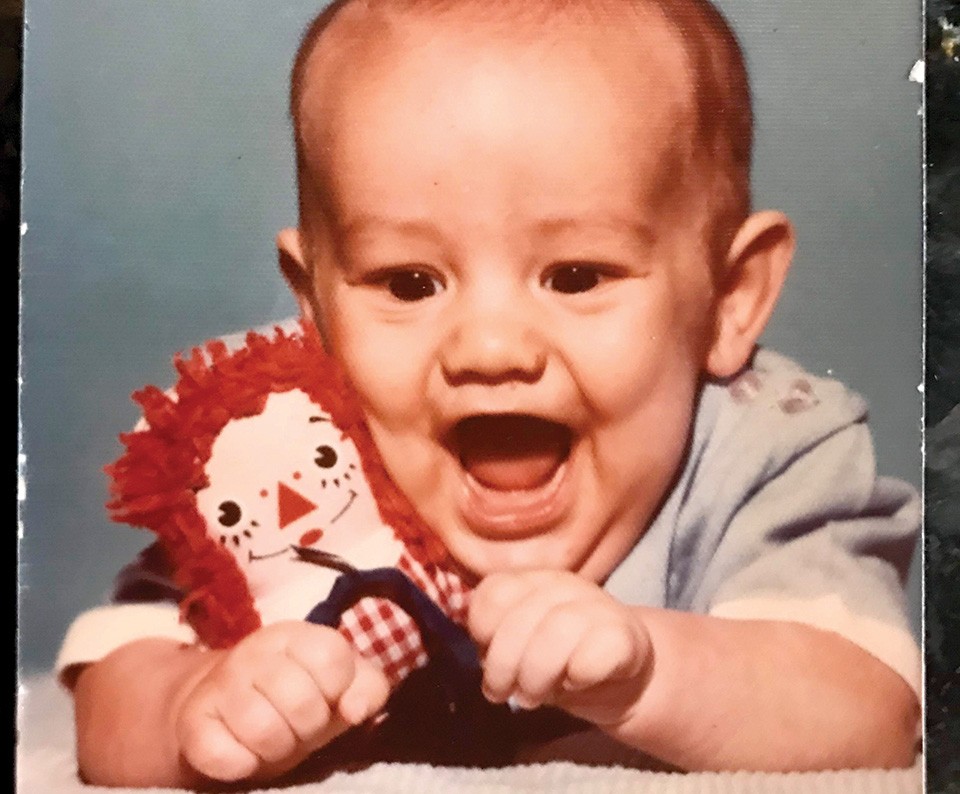

Ray Reckamp remembers the first time he saw his son.

He was at Catholic Charities' old headquarters in the Central West End. "We walked in, looked at him and my impression was he was an old man in a little bitty body," Reckamp, now 79, says. "He had a high forehead and a serious expression."

He and his wife, Judy, had decided on adoption after years of trying to have a child. They spent four years on Catholic Charities' waiting list, going to classes, preparing to become parents. When the day arrived, they named their baby Jason.

The fact that he was adopted was never secret. Judy got a sign that read, "You grew into my heart, not under it," and put it up in his room.

"That's how she looked at it, and I did, too," Reckamp recalls.

The family lived in University City. Reckamp was an engineer and Judy was a nurse. Both were smart and outgoing. In the funny way of the world, the couple was able to conceive two boys in the following years, giving Jason a pair of younger brothers. His personality varied from his siblings, but the differences among them were subtle.

"For the most part, I think Jason had a pretty normal childhood — aside from being left-handed," Reckamp jokes.

A rolling conversationalist, the father is quick to laugh and easily chats on any number of subjects. He soon noticed his first impression of his eldest as a serious little man was pretty accurate. While his younger brothers would jump right into a project, Jason was deliberate. Before he did something, he looked to others and then modeled his behavior accordingly.

"He's never been a spontaneous kid," Reckamp says. "I'd be upstairs, and I'd look out in the backyard, and he'd be mimicking Ozzie Smith's moves at second base, trying to do it exactly like he did."

Sports was another area where Jason differed from the others. His brothers, Bryan and John, had little interest. But Jason shot baskets in the freezing cold, dragged the two younger kids outside to act as hockey goalies and even made them stand in as pylons as he pretended to race down football fields. To this day, he lives in the misery of Blues' fandom. He also gravitated toward writing while his brothers were good at math.

"I remember a lot of the conversations I was on the outside, looking in," Jason, now 44, says.

Still, the differences were not glaring. It is only in retrospect that he begins to see the seemingly inherited traits that ran through the others. "I never felt all that different," he says, adding, "I had a great childhood. It seems almost nitpicky to talk about it now."

Then, less than a month before Jason turned fifteen, tragedy struck.

That year, 1989, Judy and Ray Reckamp went on a float trip with friends. The husband and wife floated ahead of the other couple and decided to hike along a cliff where they watched the sunset and renewed their wedding vows. As they headed back toward their boat, Judy slipped and fell off the edge. She was airlifted to the hospital, but the injuries were fatal.

"My mom was probably my best friend," Jason says.

Still in his freshman year at Christian Brothers College High School, he had often turned to Judy for help as he tried to sort through the confusion of being a teenage boy. He remembers that awful Sunday night when he watched through the window of their house as his father returned home alone. Judy's death upended Jason's world. He'd been quiet before but withdrew further.

He started thinking seriously about finding his birth mother. "I was trying, at least in my mind, trying to fill a hole," he says.

He looks back and realizes nothing would have mitigated the pain of Judy's death. But the loss of one mother awakened a powerful urge to find another. "In a broken young teenager, that feeling started to come to the forefront," he says. "It was just more of a pact with myself — 'I'm going to find her,'" he says.

Jason talked to his dad about the idea, and Reckamp had no problem with him trying. Still, it wasn't clear where to start. This was before the internet became a go-to source for life's mysteries, and so it wasn't until years later, when Jason was about to become a father himself, that he first made a serious effort.

He started with Catholic Charities. Parents who had given their children up for adoption could provide updates, including health information, if they chose. For a fee, Catholic Charities would check the files to see if there was anything available. It was a crap shoot. There might be something; there might be nothing. Jason wrote them a check — he remembers it being about $500 — only to be told they had nothing for him.

"All that did was piss me off," he says.

A Catholic Charities worker suggested he might have better luck with a private investigator, so Jason tried that, too. That cost him another $2,500 to $3,000 — and turned up nothing.

"I was just throwing money into the wind," he says.

Burned twice, his efforts were more low-key after that. He kept an eye on websites where other adoptees traded tips. At the end of 2016, he learned about a newly passed Missouri law. The legislation would for the first time allow adoptees to request birth records from the state without a court order. All they had to do was fill out a form and send in $15.

"I was like, fifteen bucks? Holy shit," Jason remembers.

He assumed there were would be a rush of applications when the law first took effect in January 2018, so he waited a month, filled out the form and sent in his check. Eight months later, a letter arrived.

Former state Representative Don Phillips understands the powerful hold of the unknown.

The retired state trooper from the southern Missouri lake town of Kimberling City was adopted as a baby, and like tens of thousands of other adoptees, grew up not knowing where he came from. So when a 75-year-old adopted woman asked him during his third term in the statehouse for help unsealing her birth records, he recognized a familiar ache.

"I knew exactly," he says. "I could empathize with what she was feeling and knew exactly what she was feeling."

Versions of a bill to open original birth records for adoptees had been kicking around Jefferson City for at least fifteen or sixteen years. A hard push in 2000 ultimately failed, and Phillips had no luck when he first tried in 2015.

"'Adoption' seems to be a poison word, even in today's society," Phillips says. "It's like an affliction. That's a hurdle we have to get over. We have to convince people adoption is a good thing."

As he worked on the legislation, he met Heather Dodd of the Missouri Adoptee Rights Movement, a volunteer organization. Dodd's mother had been orphaned at age six, and she and her siblings were sent to separate foster homes. When Dodd's mom tried at age eighteen to track down her long lost family, a social worker told her it was none of her business, Dodd says.

"I grew up hearing that story, knowing that we had other family out there," she says.

Dodd was eventually able to help her mother find her siblings, but she had to get creative to do it. She started by locating her grandmother's grave and leaving a note next to the headstone. The note was later discovered by relatives, who provided the first bits of information. "It took thirteen years to find every last one that was adopted out," Dodd says.

Interested in genealogy, Dodd later helped a woman in an online group track down down her dying mother, who was then in her 90s. The two experiences led her to team up with other volunteers and ultimately launch the Missouri Adoptee Rights Movement group on Facebook.

After the 2015 bill failed, the team — Phillips calls them the "Adoption Army" — came up with a new strategy. So far, discussion had focused on the harm. Opponents argued that any change to the law would essentially break the promise of secrecy made to generations of parents. That reasoning tracked with old attitudes of shame, recalling an era when pregnant teens were spirited away to "visit relatives." Unsealing records now, providing a path for adoptees to contact their birth parents, was seen as forcing women to confront dark secrets.

But Dodd and the Adoption Army were in contact with not only adoptees, but parents who had spent decades wondering what had happened to their children. "We had many, many birth mothers on our side who were really wanting their children to be able to come and find them," Dodd says.

In meetings with lawmakers the Adoption Army focused on the positives of offering a path for people to uncover their lineage. "You're really going to change people's lives," Dodd told legislators.

More than twenty states provide some way for adoptees to request their birth records. A few states, including Kansas, had never sealed them. Dodd argued that the rise of DNA testing and sites like Ancestry.com were already serving as a workaround in the remaining states, including Missouri. Providing adoptees access to their records would allow them to contact birth parents directly, rather than working backward through a DNA match to a second or third cousin, a process likely to involve multiple family members, some of whom might be learning of the adoption for the first time.

"'What sounds more private to you?' That was my question to them," Dodd says. "That's when the light bulb came on for a few of them, I think."

The Missouri Adoptee Rights Act passed easily in 2016, and it proved even more popular than Phillips ever expected.

"We knew there would probably be hundreds [of requests], but it ended up being more like thousands," he says.

The new law included a provision to allow parents who did not want to be contacted to opt out. But few did. The state was overwhelmed with applications from adoptees. Early estimates of six to eight weeks to get records ballooned into six to eight months. The Department of Health and Senior Services fielded 4,044 requests for original birth certificates between October 1, 2017, and December 31, 2018, according to the state. Slowly, the department has worked through almost the entire backlog and is now working on 2019 requests, a spokeswoman says.

Phillips, who left his legislator's job when Governor Mike Parson appointed him to the state probation and parole board, says legislators slog through bills year after year, hoping to pass something that makes a real difference. For him, the adoptees rights act was that bill.

"This was absolutely your dream come true for a bill," he says.

Most of the stories he hears are positive. But even in rare cases when parents do not wish to be contacted, adoptees at least have closure.

"The known is something people can deal with," he says.

He was 47 years old when he tracked down his birth parents. As a longtime lawman, he had the skills and resources others did not. "I was in the business of finding people," he says. And yet there was nothing that could prepare him for the first time he picked up the phone and dialed the number for his biological father.

"It sounded like me on the other end," Phillips says. "I couldn't even tell the difference. It brought chills."

Jason Reckamp's certificate of live birth arrived in the mail in October 2018.

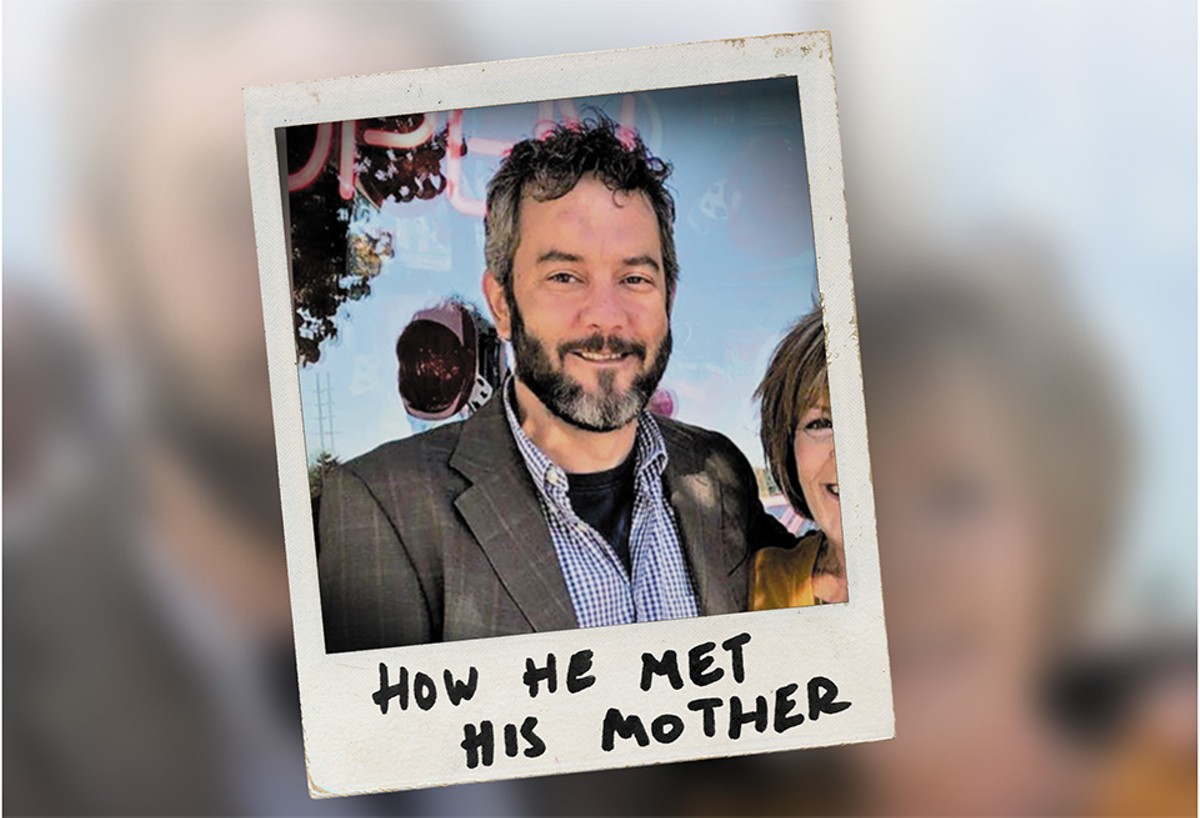

He and his girlfriend, Jennifer Patterson, stared at the name: Karen Piper. When she gave birth to Jason, she'd been sixteen and lived in Florissant. After a lifetime of mystery — not to mention a significant amount of wasted effort and money — Jason finally had the name of his birth mother.

But while it was more information than he had ever had, it was also 44 years old. Surely, she had moved, and there was a decent chance she had married and changed her last name. His biological father was not listed.

Jason and Patterson spent the night googling names and diving down rabbit holes. They would come across a possible match, pull up pictures and search for any resemblance. "It's funny how you can kind of see yourself in every person," Patterson says.

They decided Patterson would write a letter to the address listed on the birth certificate and address it to "the Piper Family," hoping it might seem a little less intrusive coming from a third party.

In the meantime, they kept searching online. Patterson, an attorney, enlisted colleagues to help. One came up with a likely person from a Classmates.com yearbook page for McCluer North High School in Florissant. Jason's sister-in-law was then able to find a crucial piece of the puzzle by locating on Facebook a Karen Piper Harty, whose profile matched the information they had available. As far as they could tell, this was her.

Jason was not sure what do with this new information, gathered in a flurry over three days.

"I went from not having anything for years to having something concrete," Jason says. "Initially, in some ways, that was worse."

It was overwhelming. What if Harty did not want anything to do with him? What if she was horrible? What if they did not even have the right person, and he had to start over? Patterson again offered to make the first contact and sent a Facebook message. It was not only that they thought it might seem less threatening for her to reach out; he had followed so many false starts, he was not sure if he could bear another.

"Every other door I had tried to knock on or open was slammed in my face, or it was just a wall," he says. "I didn't think I could hear, 'No.'"

Harty responded to Patterson's message the next day and said she would love to talk. Patterson and Harty spoke first, and then one day in October 2018, less than a week after he first learned her name, Jason picked up the phone and heard his birth mother's voice for the first time.

Patterson watched his face change as he talked. In their relationship, Patterson is the outgoing one. Jason has "always been kind of a loner," she says. But his expression that day was so pure, she pulled out her phone and took a picture. In the snapshot, his eyes are bright and his mouth open in a grin.

"I had not seen him smile like that," Patterson says.

Harty was heading out of town with her husband to celebrate their 30th wedding anniversary. But after several days away, they cut their trip short and hurried home to Missouri to meet Jason.

Harty lives little more than an hour northwest of St. Louis in the small town of Eolia and works at a rural health clinic in Bowling Green. She had previously worked in Creve Coeur and used to have an apartment in St. Peters. All this time, she and Jason had been within an hour or two of one another.

It was equally surreal for her to learn his name: Harty had called him "Jason" after he was born. She thought the Reckamps must have known and decided to keep the name, but they did not. They picked "Jason" on their own.

She reserved a private dining room at BC's Kitchen in Lake St. Louis for their first in-person meeting. She and her husband met Jason and Patterson for lunch. They arrived around 11 a.m., and Jason gave her a bouquet of flowers.

They stayed all afternoon and into the evening. Lunch turned into dinner and then drinks — and the party grew. Harty's younger son, 41-year-old Ryan Hoffman, sent his mother texts until finally they invited him to join them. "He would not stop hugging Jason the whole time," Patterson says. The group did not leave until after 9 p.m.

Jason had tried not to expect too much, but the reality has been better than he could have imagined. Harty was warm and kind. Talking to her felt natural.

"I honestly couldn't have asked for a better situation — a better person, for one, just inside and out, a great person," he says. "It's been pretty cool. It's easy to say now, but if it had been the other way, or the other end of the spectrum, I would have at least had closure."

Harty was similarly moved. She was so nervous heading into their first meeting that she did not sleep the night before. But Jason thanked her for the decision she made all those years ago. He'd had a good childhood and was raised by people who loved him. "All those things you wonder," she says. "You bring them into the world — you want to make sure he's well."

After they parted ways, she contacted someone else she had not seen in more than 40 years — Jason's biological father, Jim Lownsdale.

"I just want to tell you, I had the best experience," she told him.

Like Harty, Lownsdale had long hoped his oldest son would come calling someday. He also counted the birthdays every Veterans Day. He thought maybe after the boy turned eighteen he would hear from him, but the decades passed and he began to assume they would never meet.

"I figured for, I guess, the last ten years that it wasn't going to happen," he says.

He was in the Army by the time Jason was born. He never saw him and imagines holding the baby and then letting him go must have been gut-wrenching for Harty.

Part of him still thinks they could have made it as parents. He knows the odds were against them. They were so young in 1974, and he concedes it was likely the right call to put him up for adoption. Still, he looks back at his seventeen-year-old self and wonders.

"I'm not so sure it was as right as everyone thinks," he says.

Harty's father, Bruce Piper, brought her to visit Lownsdale at Fort Leonard Wood before Jason was born. Piper left the teens alone for the day so they could talk. Lownsdale remembers it was bitter cold. His options had been limited. He did not have any money, but the Army would house his young family. Even after Harty went home, he was not convinced he wanted to give up the baby. The process required his signature. He went to the Judge Advocate General's office on base to sign the papers but soon turned around.

"It took three trips to get me to sign," he says. "I was very reluctant."

Ultimately, it seemed like there was little he could do. He signed the forms, the baby was born and Lownsdale served his time in the Army. He and Harty lost touch while he was still in the service. He later went on to law school. He is now an attorney and lives in Chesterfield. He has four other kids and says he likes his life. "I don't begrudge anything," he says. "It was all people doing what they thought was best." But he never forgot his firstborn.

Given his profession, he says he is surprised he did not hear about the changes brought about by the Missouri Adoptee Rights Act. When he got a Facebook message from Harty one day, he was stunned.

"I'd been looking and waiting," he says. "I didn't think he'd ever come along."

He and Jason met last fall at Lownsdale's seventeen-year-old son's hockey game.

"I saw him, and it was like I'd known him all my life," Lownsdale says.

Jason had started his search for his mother. Meeting Lownsdale was more unexpected.

"Mom was easy, probably because I've been lacking one for 30 years," he says. With Lownsdale, it was initially "more just two guys hanging out. It was not a bad thing."

As they have talked, Jason has noticed a familiarity in the way they speak and think. Both love hockey and, painfully, the Blues. Jason is working on a novel in his spare time, and Lownsdale has written a couple of unpublished books. "In a lot of ways, it felt like I was talking to myself, at least in my own mind," Jason says.

Now that Jason has found his biological mother, new worlds have opened up.

He has three half siblings on Harty's side and four on Lownsdale's. He is still tabulating the number of new nieces and nephews. He has met Harty's father, his grandfather Bruce Piper, who used to be a hockey referee.

"He's a firecracker," Jason says. "He's 91, and I bet he could probably still put on skates and play."

He had always assumed vaguely that his roots spread beyond just his mother, but their nature and direction offer endless surprises and fascinations with each new introduction. He and his newly discovered relatives are moving gingerly after so much time apart. Separately, each says they are cautious not to come on too strong. It is a balance between making up for decades of lost time and also building new relationships among virtual strangers.

"We're like, 'Join the family!'" says Harty's oldest daughter, 32-year-old Carissa Lovelace. "But you want to respect that he has his own family that he's grown up with."

Out of all the half siblings he has met so far, Lovelace may be the most like Jason. Their relatives describe both as deep thinkers who consider their words before speaking. But Harty also sees similarities with other family members. Her youngest daughter Danielle is funny like Jason. Her son Ryan now spends Blues games texting back and forth with his older brother.

As for Harty, she still has only seen Jason in person about a half-dozen times, but they continue to text and talk on the phone, sometimes for hours. The relationship is still new.

"I hope that continues to grow," she says. "I pray that it continues to grow."

Patterson, who made the first contacts between Jason and each parent, has watched him slowly lower his defenses, probably for the first time in his life.

"I'm a little surprised how much he has thrown himself into this," she says. "I'm happy for him."

Patterson thinks the bond will deepen naturally between Harty and Jason, in part because Harty's outgoing nature will overcome his passive personality. But she worries that Jason's and Lownsdale's personalities are almost too similar and that they will get stuck, each waiting for the other to act first.

"I'm afraid that Jim and Jason are going to miss that," she says.

Jason is not sorry for the way things worked out. He is close with his father, Ray Reckamp, and he still thinks about Judy every day. Still, these new connections help piece together a puzzle 44 years in the making.

Talking to his birth father, he says, "I realized he wanted to do the right thing and take responsibility. I think that's all you can ask from a sixteen-year-old kid."

He and Lownsdale text and call. Neither wants to upend the other's life, but they are eager to get to know each other. In some ways, Lownsdale says, meeting Jason was like meeting a stranger who was also his best friend.

"You're not sure why," he says, "but you're with your family, and you know it."