Following a timeline that stretches from Charlie Chaplin's film debut in 1915 to the digital cinema coup of roughly a century later, film historian and restorationist Ross Lipman's Notfilm is a kind of Venn diagram in which most of the major forces of twentieth-century modernism overlap: silent comedy, Russian formalism, James Joyce's stream-of-consciousness, underground film, European art cinema and Beat poets all cross paths on a street in the Bronx in 1964.

At the center of these divergent cultural streams is an obscure short film, a collaboration between an austere Nobel Prize-winning author, one of Hollywood's greatest comic talents and one of America's most adventurous publishers. Notfilm documents the making of Samuel Beckett's experimental short movie Film, and proves that this brief cinematic effort is more than the sum of its 22 minutes. It is instead the nexus of the lives and works of its collaborators and the path that winds toward the future of the medium itself.

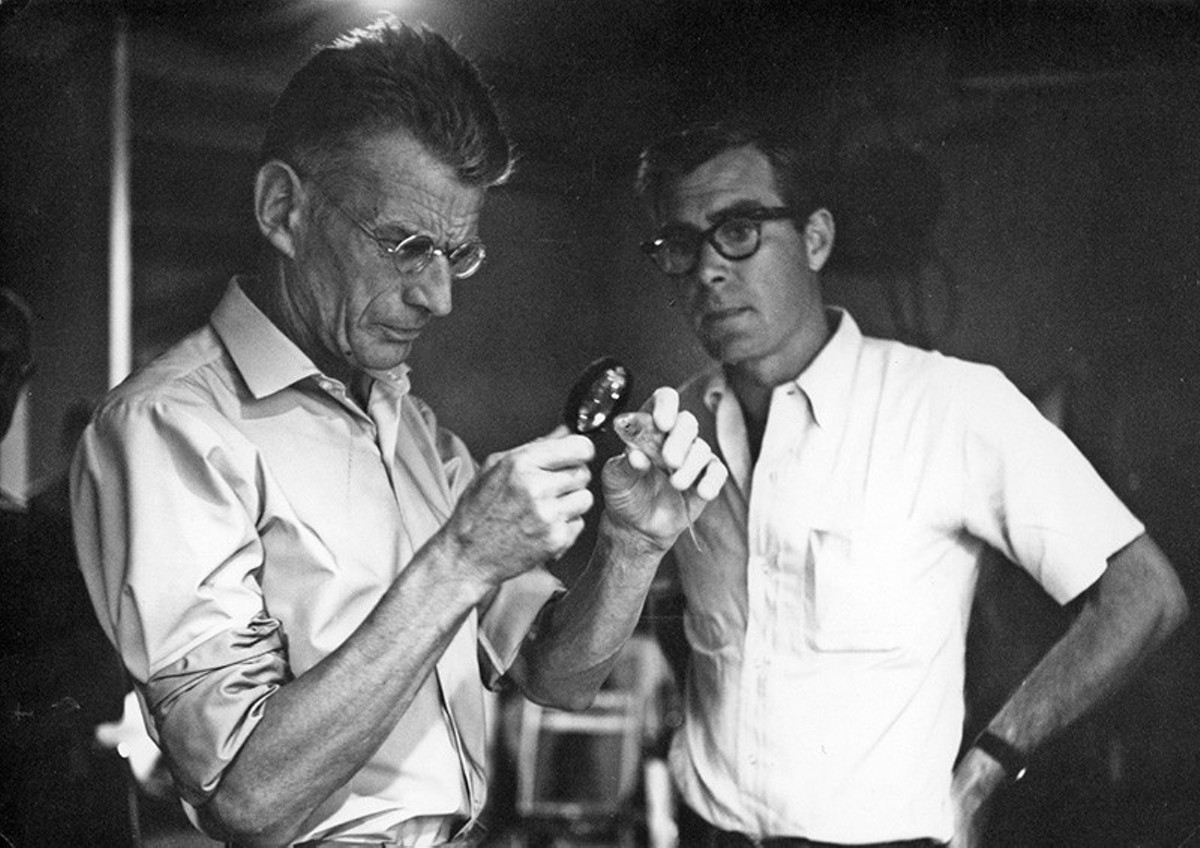

In 1964 publisher Barney Rosset, owner of Grove Press, came up with an ambitious idea to enter the film business. He commissioned a series of short subjects from authors Harold Pinter, Eugene Ionesco, Jean Genet and Norman Mailer, most of whom had either been published by Grove or contributed to its magazine, Evergreen Review. In the end, Beckett's Film would be the only original cinematic release. It was directed by Alan Schneider (who staged the first production of Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and was Beckett's choice for American productions of his work) and starred the supreme existential film clown, the great Buster Keaton.

Beckett's original idea was more a philosophical exercise than a screenplay, complete with sketches and diagrams for camera movements. Based on a concept from the philosopher George Berkeley — "To be is to be perceived" — Beckett created a symbolic battle between two characters called simply E and O (for "the eye" and "the object"). The former was represented by the camera, as the latter (Keaton) tries to escape from its gaze.

It was not an easy shoot. Beckett — who made his only visit to the U.S. for the filming — was famously uncompromising about his work. Schneider had no film experience, and cinematographer Boris Kaufman, an Academy Award winner who provided a link to the avant-garde past as the brother of Soviet cinema pioneer Dziga Vertov, struggled to translate the author's abstract ideas into actual imagery. Even Keaton, who had also explored the subjectivity of the camera in his films Sherlock, Jr. and The Cameraman four decades earlier, was at a loss to explain what he was doing. (Outtakes from the film show Keaton developing minimalist gags for his character, none of which made the final cut.) In one of the many discussions and script meetings included in Notfilm, Schneider laments, "We will all have made a movie and wished that we hadn't."

It's also not an easy story to recreate for a documentary. Most of the participants have passed away. There are second-hand reports from film historian Kevin Brownlow, who interviewed Beckett about Film years later, and also from actress Billie Whitelaw, who performed in Beckett's solo piece Not I. Critic Leonard Maltin, who visited the set as a fourteen-year-old to get a glimpse of Keaton, shares what he recalls as well.

Much of the information comes from Rosset, who died in 2012, and whose memory, Lipman acknowledges, was faulty. Fortunately, the same can't be said for Rosset's archives, which include a reel containing a deleted scene and a tape recording (made in secret) of a script meeting, one of the few occasions Beckett's voice was captured on tape.

Lipman, in a nod to Vertov, calls his film a "Kino-essay," but it's an essay in the broadest postmodern style with digressions, speculation and even an intermission. Ideas and artistic movements crash and entwine but are neatly resolved before the film ends. Just as Beckett's title suggested that his Film was a self-contained look at its own process, Lipman's Notfilm proclaims its own limitations in its title. It's Notfilm, because it's one degree removed from the 1965 work; because it's about the unconventional stretching of the medium by Beck, Keaton and their precursors; and finally because of the advent of the digital era — nearly every modern film is now also "not film." With its wide intellectual range and an energetic ability to reach in every direction, Notfilm is a unique, heady achievement worthy of its subjective subjects.