On June 18, the candidates for St. Louis circuit attorney gathered for a debate unlike any in the city's long history. Held before a crowd of 270 in a sun-lit conference room on the campus of Saint Louis University, the session had been organized by Black Lives Matter protesters and local social justice organizations. A key moderator, Kayla Reed, had confronted police in Ferguson and St. Louis. Like others in the audience, she knew what it was like to be arrested for protesting.

It says something about the mood of the electorate in St. Louis these days that all four candidates vying to become the city's top prosecutor didn't just show up for the debate — they earnestly made their case for reform to the office's harshest critics. Two veteran prosecutors, a retired police officer and a state representative all participated for nearly two hours, answering question after question about public accountability, mass incarceration and eliminating racial bias in the criminal justice system. Not one of them ever suggested that the organizers' concerns were overblown, or that they lacked authority to challenge law enforcement.

That response came from outside the room.

Jennifer Joyce, who for sixteen years has served as the city's circuit attorney, the woman the four candidates were seeking to replace, wasn't at the debate — but she was, apparently, closely following while St. Louis Public Radio's Rachel Lippmann live-tweeted the action.

"Odd that @RE_invent_ED is moderating a Circuit Attorney debate when she's made it clear she wants to blow up the system. Seems unbalanced," Joyce tweeted an hour into the event, using Reed's user name.

Joyce took some shots at the candidates, too, but returned several times to decry the bias she saw in the debate's setup.

"This is completely false," she tweeted an hour later, responding to a moderator's suggestion that success in the Circuit Attorney's Office is judged by conviction rate. "We've never measured success on convictions. This is where we need balance on the panel."

Those actually attending the debate took umbrage at the prosecutor's sideline commentary. One audience member, Rasheen Aldridge, diagnosed Joyce's petty outrage as an afternoon case of tweeting-under-the-influence.

"When the city of St. Louis prosecutor is at home on the couch sipping something and just mad for no reason," Aldridge tweeted at Joyce, adding three crying-with-laughter emojis.

Others in the crowd piled on. "You as the CA in this town must be alot like like [sic] being a weather forecaster," tweeted Kennard Williams, a protester and local activist. "Be wrong all the time, but still have a job."

Later, Joyce would apologize, saying she had been out of line (and, for the record, hadn't been drinking — she is a teetotaler). But the moment stood as a stark reminder of what's at stake in August.

In St. Louis' criminal justice system, all roads lead to the desk of the circuit attorney. The job of the city's top prosecutor is grueling and frequently thankless, a lightning rod for criticism even in the best of times. The office comes with the power to not only charge suspects with misdemeanors and felonies, but to set policies that change lives in both communities and courtrooms.

Yet once elected, the circuit attorney tends to get reelected. Only three people have held the title since 1976. Joyce breezed through the last two contests unopposed.

One year ago this month, Joyce surprised allies and enemies alike by announcing she was would not run for an unprecedented fifth term.

It had been a hard couple of years for the circuit attorney's office. The August 2014 police shooting of Michael Brown, a black Ferguson teenager, mobilized protesters who sought to scrutinize not only Brown's death in St. Louis County but also how prosecutors were handling police shootings in St. Louis city.

And scrutinize they did. In the span of two months following Brown's death, St. Louis metro police shot and killed two young black men. Joyce's office investigated both cases, but chose not to bring charges against the officers. After the second case failed to yield criminal charges, protesters showed up on Joyce's front porch. Seven were arrested on the scene.

The organizers of the June 18 debate didn't try to hide their anticipation for Joyce's departure. The debate's printed program, distributed to attendees, featured suggested hashtags for live-tweeting the event. One was #ByeJennifer.

Now the candidates vying to replace her face a formidable task. They need to convince voters that they have the experience to prosecute murderers and rapists, but also hold the police in check. They need to show they care about victims, but — in this increasingly complex political climate — also show that they don't want to bring down the hammer on poor defendants.

In essence, they need to show they can both fill Joyce's shoes and bring major change. That the two goals may be mutually exclusive doesn't bother Reed, the debate moderator targeted by Joyce's derision.

"I think it's OK to live in the tensions of both," she says. "Instead of just blindly saying what Jennifer has been, I wanted to give the candidates some space to show us what they are."

Of the four candidates running in the Democratic primary, two currently work for Joyce. Since St. Louis tends to lean hard to the left, the winner of the primary vote on August 2 will almost certainly become Joyce's successor.

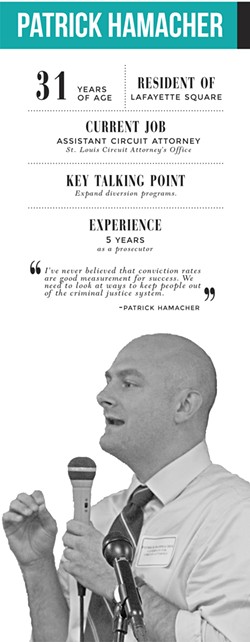

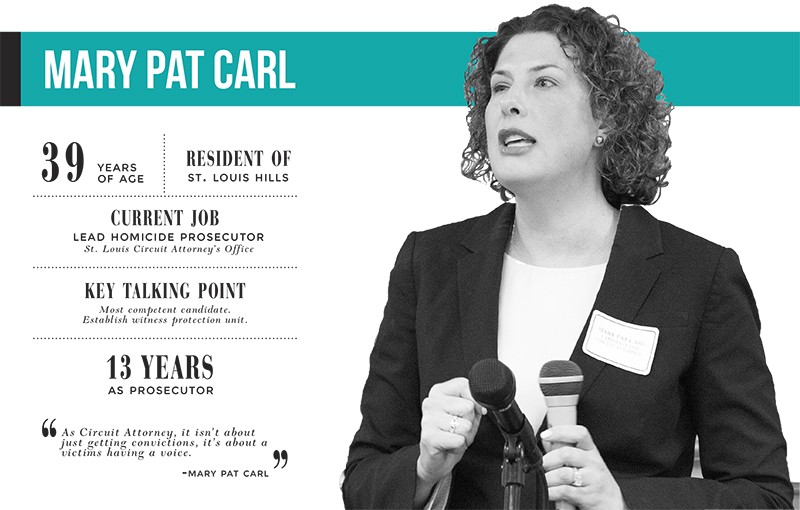

Mary Pat Carl, the lead homicide prosecutor in the Circuit Attorney's Office, has been endorsed by Joyce and has the double-edged sword of being her heir apparent. Patrick Hamacher, a prosecutor in the Circuit Attorney's Office, has five years' experience under his belt and seeks to position himself as an idealistic (yet capable) alternative to the establishment Carl.

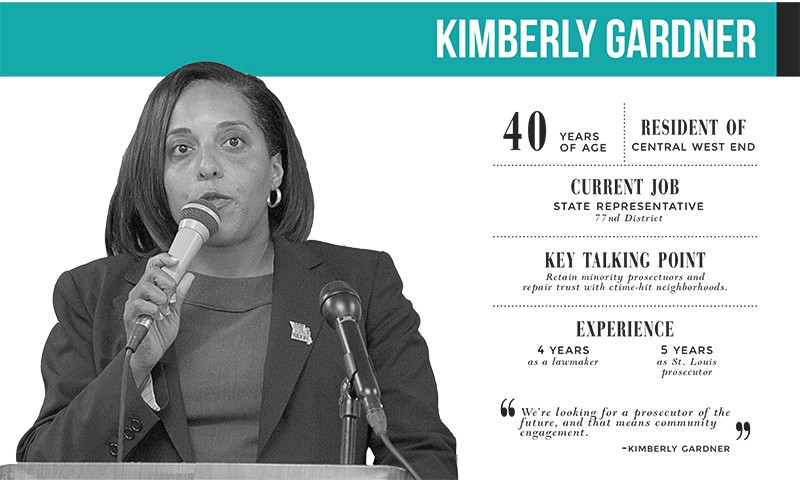

State Representative Kimberly Gardner is a black former prosecutor and nurse who left the Circuit Attorney's Office in 2008 to pursue politics in the state legislature. The true outlier is Steve Harmon, a former metro police officer and son of St. Louis' first black police chief (and later mayor), Clarence Harmon.

All four are licensed attorneys, though two — Harmon and Gardner — have never prosecuted a murder case. Harmon is the only one who has never worked for Joyce.

As outsider candidates, Harmon and Gardner took the hardest lines on Joyce. They needled at her office's lack of diversity and faulted her leadership for failing to engage minority communities. Unsurprisingly, Carl and Hamacher shied away from directly bashing their current boss, but both argued the office should do more than simply lock people up.

"I respect her office, but at the same time the challenges of yesteryear are not the challenges going forth," Gardner said in an early moment of the debate. "When you talk about how we move forward, that's about building trust, and I'm the only candidate on this stage who is able to do that."

In a debate full of tough questions and implied comparisons to Joyce, the candidates did their damnedest to stand out. After Gardner's opening salvo about how she was "the only candidate" who could return trust to the Circuit Attorney's Office, the others leapt to add their own self-declared superlatives.

"I'm the only candidate with managerial and administrative experience," Harmon said, touting his lengthy career as a homicide detective and police commander.

"I'm the only candidate who as a prosecutor has successfully diverted non-violent individuals out of the criminal justice system," said Hamacher. He launched into a stump-speech anecdote about a seventeen-year-old he'd personally mentored through probation, avoiding a life-altering conviction that could have saddled the youth with a felony conviction.

Carl took a somewhat different approach. Battle-tested over thirteen years, she rose through the ranks of the Circuit Attorney's Office while handling domestic abuse and other special victims' cases, including 36 rape trials. In speeches, she likes to point out that she has more years of prosecutorial experience than the other three candidates — combined.

"Being tough on crime, that alone isn't enough. We have to be smart on crime," Carl told the audience. "I'm the only one in this race that has the experience and the know-how to know the difference."

Considering her links to Joyce, Carl should have been the candidate on the hot seat in this particular debate. And most of the time, she was, though she handled herself with aplomb. When her opponents offered rambling tangents, Carl spouted off paragraphs of detail without as much as an "um" to interrupt her argument.

And at the conclusion of the debate's first round, it was Harmon who managed to irk the audience.

The former cop is nobody's apologist. He wears a chunky gold ring with the emblem of the St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department on his right ring finger. Back in 2005, he reported a detective to Internal Affairs after watching the officer abuse a prisoner with a stun gun. He retired from the force two years later, though he says the two events were unrelated.

But an outsider black candidate like Harmon should have been ready for the final question of the debate's first round. Instead, he stumbled.

Addressing all four candidates, Reed asked them to explain answers they'd provided to a pre-debate survey. The survey had asked them to choose among four statements: "Black Lives Matter," "All Lives Matter," "We Must Stop Killing Each Other" or "I'd rather not say."

Of the four, three candidates had picked Black Lives Matter.

Carl answered first. "Though it is true that all lives matter, right now we need to concentrate that black lives matter because they're not mattering enough."

"Of course black lives matter," followed Gardner. "I'd like to say I live a black life. So I understand the issues in terms of how African Americans are treated in the criminal justice system."

Hamacher offered a slightly different take. "To me, Black Lives Matter stands for a movement," he said, noting that it was the movement that focused awareness on police shootings.

Then came Harmon. "I answered All Lives Matter," he said.

The crowd was silent.

"I was raised in a Christian household," he continued. "As a former St. Louis police officer, I've treated all people the same, regardless of their race, ethnicity, their background, where they lived, their sexual orientation. I believed that everyone's life is equal and all lives matter."

It was not the message this audience wanted to hear. And from his seat in the audience, Rasheen Aldridge cringed.

The Ferguson protester had served on the Ferguson Commission, met President Barack Obama and is now part of a wave of young activists entering the political arena, running for committeeman in the 5th Ward.

"Being a protester, what shocked me was when Harmon said All Lives Matter," Aldridge later explained. "The movement has fought on this over and over. It's not about all lives, not about black lives. It's about how people of color are being locked out of opportunities."

On a muggy weeknight days after the debate, a St. Louis Hills neighborhood meeting opens with a special ceremony. Carrying the gravitas of a kindergarten graduation, a representative of the St. Louis Grand Jury Association presents a middle-aged woman with a certificate and a medal. Her heroic act? Calling 911 on a man stealing copper wiring.

"This wasn't rescuing a family from a burning building," she acknowledges, accepting the gifts. "What I did is something very simple that any of you could have done. I looked out of my kitchen window, and I used my voice to call the police."

Hamacher joins the modest crowd — 35 sweating attendees, all white — in a round of applause. Since launching his campaign, he's attended four or five neighborhood meetings every week, all over the city. This one, in one of the city's safest areas, is just one of many.

After the neighborhood's regular business concludes, Hamacher is provided a few minutes to pitch his candidacy for circuit attorney. He opens by congratulating the night's honoree.

"I know we wish that we had more witnesses and victims just like yourself," he says. Meaning: The kind who aren't afraid to call the police.

He launches into one of his stump speeches.

"I was about fourteen years old when I knew I wanted to be prosecutor," he begins. "I used to love shows like Dateline and 20/20. I used to watch them with my mom. I was really interested in the stories they would tell, but especially the prosecutors in those cases."

Born in Brentwood, the DeSmet grad attended Loyola before studying law at Mizzou and getting a chance to live his teenaged prosecutorial dream while interning in the Cook County prosecutor's office in Chicago. After he passed the bar, Joyce hired him to join her office in St. Louis.

"We have some really big problems," Hamacher tells the room. "We have some violent crime issues here in our city. Distrust in the criminal justice system. We really need someone as the next circuit attorney who has the leadership ability to really bring people together to address these issues."

So far, Hamacher's youth and idealism has worked on the campaign trail. His emphasis on diversion programs and the need for special prosecutors to investigate police shootings has won him allies with activists and an endorsement from the Ethical Society of Police, the St. Louis equivalent of a black police union.

But he's also struggled in head-to-head comparisons with his co-worker, Mary Pat Carl. The office's Lead Homicide Prosecutor, Carl has tried eight murder cases and oversaw several additional trials while training other prosecutors. Hamacher has tried just one murder case. And at 31, he'll have to work overtime to persuade voters he's not too young for such a big job.

Hamacher isn't the only one struggling to outshine Carl. Like Hamacher, Kimberly Gardner also spent about five years as a St. Louis prosecutor, handling misdemeanors and some felony cases, but no murders.

But Gardner's lack of big-case experience isn't something to overcome in her telling; in fact, it's part of her sales pitch.

"As one of the rare minority prosecutors, I felt there was not a lot of opportunity for me to move up within that organization," Gardner says during an interview in her campaign office. "That's why I only stayed there for a certain amount of time. As a lawyer you want to expand yourself. You don't want to be limited by duties or functions of the office. They need to do a better job of retaining good talent and diverse culture."

For Gardner, the race is about more than prosecutorial experience. She notes that the violence that continues to bloody the streets in north St. Louis neighborhoods — where most of the city's murders take place — has roots in poverty, over-policing and longstanding imbalances in education and transportation. The residents there are disheartened, says Gardner. Where she's from, witnesses and victims are afraid to call 911.

"It's the system where they feel like they have no voice. No one can identify with the struggles in some of these hard-hit, economically depressed areas. I think I can go in and bridge the gap."

Gardner is attempting to walk a narrow line here: Sure, she doesn't have Carl's career chops as prosecutor — but she also embodies why young black lawyers seem to keep leaving the Circuit Attorney's Office for other pastures.

"I know a lot of lawyers who would love to have the opportunity to work in the prosecutor's office," she says. "But opportunities are limited. Space is limited. This idea we cannot have a diverse prosecutor's office — that's not true."

Six days after the debate, Jennifer Joyce sits in her wood-covered office on the fourth floor of the Carnahan Courthouse, turning a snow globe in her hands. She gives it a shake.

"This is my Lady Justice snow globe," Joyce says. Gold foil billows around the female figure encased in glass. "Somebody gave it to me because I change this office all the time. I call it snow-globing the office."

Now Joyce's impending departure portends a shake-up that hasn't been seen in the office in more than a decade.

"I care very much about this office, and I care very much about who succeeds me," Joyce says. "The work here is so important, and there's a lot of people doing this work and I'm going to correct any misrepresentation by anybody."

That's why the debate worried her. The stakes are too high for platitudes and fuzzy propositions about bringing trust back to the office. The next circuit attorney won't have any time for on-the-job training, she says. There is work to be done, and it waits on nobody.

But even Joyce can admit when she's gone too far. Little more than two hours after the debate ended, Joyce backtracked on her Twitter barrage. She tweeted at Reed, "[M]y apologies. Looks like I'm the one who lacked balance. By all accounts you did a great job."

The difference between her initial tweets and the apology, Joyce says, was a conversation with Bruce Franks, an activist who makes it his habit to bridge the divide between protesters and the police. He had reached out to Joyce and chided her over her easy dismissal of the debate. Joyce apparently took his words to heart.

"It was pretty unfair of me to not be at the debate. This is a young woman who cares really passionately about this stuff and worked really hard on this," Joyce says of Reed. "By all accounts the questions were fair. I was prejudging what she was going to do, and that's exactly the thing that protesters do that annoys me. I realized that was a mistake on my part."

It's not often that Joyce reverses a position. On her desk sits a plaque with the words "I'm Responsible," the same kind Rudy Giuliani kept on his desk while mayor of New York City. Over the last several years, Joyce earned a reputation for being prickly on Twitter, willing to throw down in defense of her office for any perceived slight or misrepresentation. Trying to budge Joyce from a position can often be a doomed effort.

She acknowledges that she overreacted to the debate criticism, but she also knows what the next Circuit Attorney will be walking into. It won't be anything like an echo chamber of progressives.

"They're going to have to know what they're doing," she says.

It's not just a matter of years spent in the office. Joyce had only six years in the prosecutor's office before winning the circuit attorney post in 2000. But unlike Hamacher or Gardner, Joyce had worked multiple homicide cases and spent her years in the high-stakes child abuse unit.

Not one to mince words, Joyce offers a simple assessment of Hamacher. "I don't think Patrick has the experience to do this job," she says.

Joyce has similar problems with Gardner. She can pound the bully pulpit about bringing trust back to the office, but to Joyce it sounds like empty political fury.

"Kim was a prosecutor here for five years. She's had that experience where victims are afraid to come forward or afraid to cooperate and we have to dismiss the case. Why is it now, when she sits in that chair, that all of a sudden all the victims are going to come forward? It's not that easy."

If there's one point about the job that Joyce wants to get across, it's just that: There is nothing easy about being circuit attorney. The holder of that title will find him or herself threatened and pressured on all sides, pushed by police unions, legislators, mayors and high-powered attorneys. The next circuit attorney may look out their window one day to see protesters assembling on their lawn, as she did.

"I think this is, in some ways, the most important election," Joyce mused. "I like Kim Gardner a lot. I like Patrick Hamacher a lot. I don't really know Steven Harmon. But nobody is in the same league, in my view, as Mary Pat."

When Mary Pat Carl introduces herself to a jury, she takes time to explain the story behind her face.

After giving birth to her second child, Carl was diagnosed with Bell's palsy, a condition that causes facial nerves to swell. Overnight, Carl, who'd eventually have four kids, was unable to control the muscles on the right side of her face. Although most cases of Bell's palsy are temporary, Carl wasn't so fortunate. Five years after the diagnosis, her smile remains lopsided.

After returning to work, she seriously considered giving up trials for good.

"It was obvious that I had a choice to make," Carl says on a recent weekday outing to meet voters in St. Louis Hills. "Walk away from what I loved? Walk away from my passion? Or put vanity aside and figure out a way to do it?"

Carl settled on the latter option. These days, when she stands before a jury, she recounts the story of her diagnosis and warns the jury that sometimes it looks like she's smirking when she's not. She'll also give jurors a chance to speak up if they feel her appearance is so distracting they can't focus on the case. No one ever has.

The day's heat index is tipping at 103 degrees, and the air has turned to soup. Clutching a stack of campaign pamphlets in one hand, Carl peers at a smartphone app that directs her to the next address of a likely primary voter.

After growing up in Florissant, Carl attended high school at Incarnate Word Academy and claimed her bachelor's at DePaul University in Chicago. She graduated law school at Washington University in 2002 and spent a year with St. Clair County in Illinois before moving to the St. Louis Circuit Attorney's Office.

The following thirteen years threw Carl into homicide cases as well as felonies related to guns and drugs, but it is the child abuse and domestic assaults that stick with her. Witnesses and victims need more protection, Carl says, which is why she wants to create a special witness protection unit in the Circuit Attorney's Office.

And although she's proud to have Joyce's support, she acknowledges that the endorsement has caused its share of problems.

"People think that I am the exact same as Jennifer because I have her endorsement," Carl says. "I'm honored, but it doesn't mean I've become a replicant of her DNA."

Carl approaches a stately brick house on Itaska Street. After some knocking, a trim, middle-aged man opens the door. Carl introduces herself, asking if the man has looked at the circuit attorney race yet.

He hadn't. "I just don't read the paper," he says sheepishly.

But it turns out the man shares a mutual friend with Carl, a public defender in the city. Carl and the man banter back and forth for minute. Carl pitches her candidacy for circuit attorney and lays out her experiences as prosecutor.

The man spends several minutes complaining about nursing school. Then he takes a pamphlet.

"Well, listen, thank you for what you do," he finally says. But he doesn't close the door just yet. "You are probably not the most popular person is some circles because of what you do, but it's important. So thank you, and I wish you the best of..."

The words seem to catch in this throat.

"I'm not going to say luck," he says, "because you have the experience."

Follow Danny Wicentowski on Twitter at @D_ Towski. E-mail the author at [email protected]