By reputation, the Proud Boys are fighters.

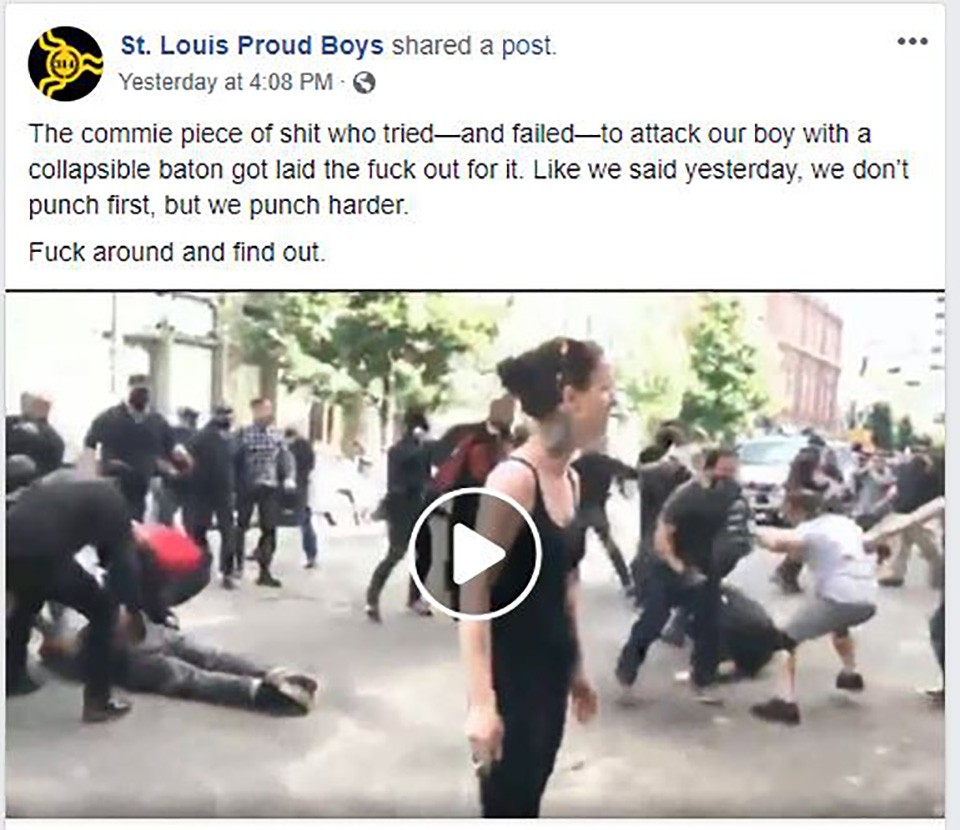

This past August, the far-right group gathered on the streets of Portland with its fellow travelers for a rally all but guaranteed to start a brawl. On one side were young men in MAGA hats wearing distinctive black polo shirts with yellow piping on the collars and sleeves. On the other, an assortment of avowed anti-fascist groups commonly lumped together as Antifa. The two sides circled, cat-called and then, inevitably, tried to knock the crap out of each other.

Sticks, shields, bricks, bottles and mace were deployed, as small groups and individual brawlers clashed amid the sound of police flash bangs and homemade mortars. Both sides came prepared with helmets and homemade body armor.

For the Proud Boys, fights like these are good for their image — a powerful advertisement to their ideal recruits. On the flip side of that empowerment is bitterness. The group thrives on painting itself as a victim of left-wing persecution.

The Proud Boys organization is less than two years old, and has spent its entire existence fending off accusations that its members are part of a violent gang of white supremacists. In 2017, the Southern Poverty Law Center classified it as a "general hate group," a title the Proud Boys fiercely contest.

What is undeniable, though, is that some members of the Proud Boys have appeared uncomfortably close, figuratively and literally, to modern-day Nazis and white supremacists. Jason Kessler, a Proud Boy who was since excommunicated, organized the infamous 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville. Other Proud Boys attended.

While the most active Proud Boy chapters operate on the coasts, smaller ones have opened in cities across the country, including two in Missouri: in Kansas City and St. Louis. One estimate places total membership across the U.S. at 6,000. Numbers are growing. But the attention has its costs.

This has been a generally terrible summer for the St. Louis Proud Boys. They've been hounded by local Antifa groups. On lampposts, signs appeared blaring the members' names and photos beneath a warning: FASCIST ALERT. A placard in a storefront window proclaimed "Proud Boys Not Welcome." And while in Portland the Proud Boys met street fighters, in St. Louis they were confronted with something much trickier: a social media onslaught directed at both them and any venue unfortunate enough to host them. They've been run out of two bars — and had their private Facebook groups infiltrated.

In July, Riverfront Times received an email from a Milwaukee, Wisconsin-based "anti-fash collective" calling itself Right Wing Leaks. Posing as a recruit via a fabricated Facebook account, the collective managed to pass the Proud Boy vetting process and gain access to a closed Facebook group for Missouri Proud Boys. Right Wing Leaks then captured screenshots of members' Facebook profiles and about two dozen videos of the St. Louis chapter's initiation rites.

In one video, the president of the St. Louis chapter, a white guy with windblown black hair and aviator sunglasses, records himself taking the Proud Boy pledge.

"My name is Mike Lasater," he says in the video. "I'm a Western chauvinist, and I refuse to apologize for creating the modern world."

Lasater flashes an "OK" gesture, his index-finger and thumb joined to make an O along with three raised fingers.

He finishes the pledge. "The West is the best," he says.

On the first Friday in August, Mike Lasater and two other Proud Boys settle on stools in a south-city bar. They're drinking the group's preferred beverage combination: Budweiser and straight shots of Maker's Mark.

The bar, Tuckers, is a rarity for St. Louis. Not to be confused with Tucker's Place, the well-loved trio of local steakhouses, this Tuckers is located so far south in the Patch neighborhood, it's practically St. Louis County. It has a dive bar's classic grungy charm — at 8:30 on this Friday night, karaoke night, the regulars are already blasted and teetering on their feet. But not many establishments in this deep-blue city hang a sign above their front door stating, in giant red letters, "TRUMP." Below that, the sign, a veritable jumble of messages, shouts "St. Louis needs jobs and I need customers!!!" and "Support Your Police."

Tuckers is the closest thing to a safe space that the Proud Boys have in St. Louis.

On the TV above the bar, the Cardinals are playing the Pirates. The Pittsburgh players' black-and-yellow jerseys bear an uncanny resemblance to the tightly fit, black-and-yellow Fred Perry polo shirts worn by the three Proud Boys huddled at the bar's least crowded end.

These three identically-clad young men, all in their late twenties, are talking about Portland.

"It actually proved one thing, and it's that Antifa are the aggressors," says Luke Rohlfing, a St. Louis native who travels the U.S. while writing for the right-wing news site Big League Politics. Rohlfing spent his morning tracking livestreams and Twitter feeds of the August 3 Portland action, which he then used to opine about how the leftists were to blame for the confrontation.

Next to Rohlfing, Lasater tips his beer in agreement. The Proud Boy chapter president wears two matching gold-leaf collar pins on his polo. His belt buckle spells out "candy," and a gold medallion rests in a thicket of exposed chest hair. By Proud Boy standards, he's as flamboyantly proud as they come.

"Left to our devices, we're not a violent organization," he says.

In conversation, Lasater tends to downplay the role of violence in the group's DNA, focusing instead on similarities to traditional fraternal organizations, men's clubs, the Freemasons and Knights of Columbus.

"We're a drinking club," he says, gesturing at the bar around him. "I mean, as the St. Louis Proud Boys, what have we done since we started? We've gone out for beers, and we've made friends."

Perhaps. But they've made enemies, too. Lasater founded the local chapter in spring, not long after (as he tells it) a business partner at the bar he co-owned, the Livery Company, decided to out him on Facebook as a Trump voter. The partnership broke down from there, and he says he was forced to abandon his role.

The bar's co-owner, Emily Ebeling, says Lasater's departure had nothing to do with his political views, but admits that she was the one who publicized his vote for Trump.

"I did call him out for voting for Trump," she says. "I considered him a friend, a close friend, and he had lots of friends who Trump wouldn't protect. As a woman and a gay woman, I felt betrayed that he could vote for what Trump stands for."

Lasater says his path to far right began rather far on the left. He voted for Obama in 2008 as a "socialist-leaning Democrat," but his politics shifted as he started watching Fox News. He says found himself agreeing with what he saw on the channel, and eventually came to understand that much of what he'd assumed about Republicans were lies woven by the real bullies: the left.

In November 2017, Lasater underwent the first degree of the Proud Boy initiation — recording himself stating the pledge, "I am a Western chauvinist, and I refuse to apologize for creating the modern world."

The second degree, also filmed, involves a mock brawl that doesn't stop until the initiate can recite the names of five breakfast cereals. According to Lasater, it's meant to be a parody of gang culture, that age-old test of loyalty wherein a new member is beaten senseless by his soon-to-be brethren. In the Proud Boy version, the punches are usually thrown at low strength, and the only test is one of total cereal recall under physical duress. Also, everyone involved is drunk.

The filmed scenes of this ritual are exceedingly strange, clip after clip of a young drunk man declaring "The West is the best" before getting lightly pummeled by a circle of other drunk young men. At times, the initiate is laughing while gasping the names, "Cinnamon Toast Crunch! Cheerios! Frosted Flakes!"

"Our cereal beat-ins are our wackiest thing," concedes Rohlfing.

Of those present, he's the only Proud Boy who's managed to attain the third degree, which simply requires getting a "Proud Boy" tattoo. The fourth degree is reserved for the fighters, those Proud Boys who have "endured a major conflict related to the cause." Lasater says no one in St. Louis has attained that distinction.

As for "Western chauvinism," Lasater claims the phase isn't intended to evoke swashbuckling misogyny, but rather a kind of unapologetic patriotism.

"We are far right. Far right is an appropriate designation for us," he insists. Still, he maintains there's a difference between the Proud Boys' vision of Western culture and the ideas trafficked by the far far-right, those explicitly racist and neo-Nazi groups who utilize the term as a usefully neutered stand-in for concepts of white supremacy.

But on this Friday night, amid all the shifting semantics, the Proud Boys at times struggle to define their own terms. "Western civilization," the object of their patriotic chauvinism, seems to cover America's accomplishments and recede at the edges of its failures. Capitalism? That's Western civilization. So too is the moon landing.

Even enshrining a woman's right to vote, they claim, is part of Western civilization. Lasater notes that the triumph of women's suffrage (enacted more than a century after the signing of the Declaration of Independence) was an example of progress that wasn't "forced," but was rather ushered by "men that thought it was important, saw it as an injustice and made that correction."

Above all, they seem most committed to the concept of not apologizing.

"You can move forward without having to sit back and whine about the past," adds Rohlfing. "It's time to look forward and see that Western civilization is the best civilization."

To the Proud Boys, perhaps, this rhetoric is compelling, but outside the bubble of the group, that sort of convoluted jargon — "No, see, what chauvinism really means ..." — requires an audience willing to accept its definitions.

Lasater brings up an April Proud Boys meet-up at Keyper's Piano Bar.

"It was my first experience being recognized as a Proud Boy," he says. "'This girl comes up to us, and she's like, 'You guys are fucking Nazis.'"

Nazis. Fascists. Racists. By April, the labels were following the Proud Boys around St. Louis. Local Antifa groups mounted a campaign of public shaming, outing Proud Boys in widely shared Facebook posts. After they were spotted at Keyper's, Antifa shared a Facebook post targeting the gay bar. One flyer summarized the anti-fascist campaign in three succinct exclamations: "Boycott! Downvote! Disrupt!"

Back at Tuckers, Friday night is winding down. Outside the bar, a third Proud Boy is talking about how the group is a brotherhood — the first time he put on the black polo, he says, "I felt like I became a man" — when the door from the inside opens.

"I don't mean to interrupt, but what organization are you guys?" The question comes from a middle-aged man. He doesn't sound drunk. He sounds serious, and somewhat wary.

Rohlfing launches into the Proud Boy spiel. "We're a pro-West organization," he says. "We love America. We love Trump mostly. When it comes to things like masculinity, just being men, we promote family values."

Lasater adds, "We're always looking for more people if you're interested."

But the man is not interested in taking the pledge as a chauvinist and reciting breakfast cereals. He says he's a Trump supporter himself, but he'd only heard about the Proud Boys after they brought controversy to a nearby deli. The man tells the Proud Boys that the deli owners had received messages threatening to burn down their restaurant, even death threats, after "anti-racists" discovered the far-right group was meeting there.

"I've been hearing a lot of bad things, and I'm not respectful to that," the stranger says.

The three Proud Boys take turns responding over the next several minutes, explaining that the threats came from "crazy leftists" and communists who want to "destroy America and everything it stands for."

Soon, the man seems less wary of the Proud Boys. His demeanor changes, less an interrogator than someone genuinely confused, or lost, like a motorist asking for directions on a strange country road.

"Tell me," he asks the Proud Boys, "Who are these anti-racists?"

The River Des Peres Yacht Club is not an actual boating club, of course. The deli is located just north of its namesake, a waterway that once functioned as the city's open sewer and now flows only when filled with storm water or runoff.

The name is a St. Louis inside joke, an ironic note for a blue-collar shop known for its sandwiches. But in July, the place gained a wave of new attention not for its food, but for serving the Proud Boys.

After being outed at Keyper's, the Proud Boys fled south, to what they'd hoped could be their new meeting place. (Among other reasons, a Proud Boy worked there as a bartender.) But word quickly got out, and on July 19, more than a dozen activists flooded into the sandwich shop.

Facing the owners behind the counter, the group demanded "physical follow-through" to reports that they had agreed to ban Proud Boys from holding meetings at the shop. The protesters delivered a statement, a copy of which was later posted to the Facebook group Community Power Network St. Louis.

"You have made it clear that because of a massive display of outrage from the community that you no longer wish to be affiliated with or host Proud Boys in your establishment," the message began.

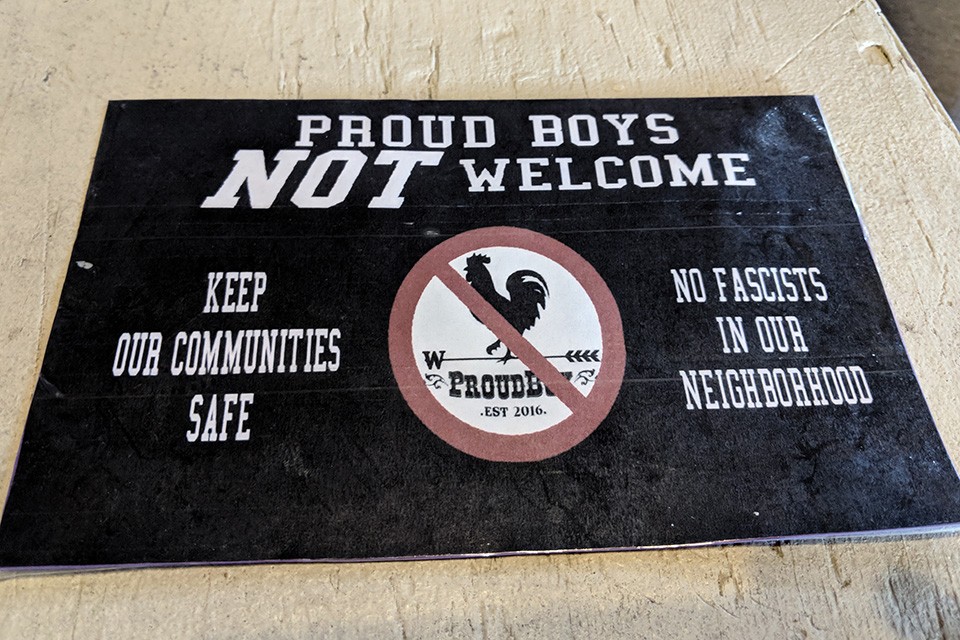

Previously, it continued, the owners had agreed to put a sign in their window to demonstrate that their former customers were now barred. The activists had brought just such a sign, printed out on separate sheets of paper and then taped together to make a glossy final product. "Proud Boys Not Welcome," it proclaimed, followed by "Keep Our Communities Safe" and "No Fascists In Our Neighborhood."

Up until that day, the campaign to drive the Proud Boys from the Yacht Club had been waged almost entirely online. The statement described the sign's manifestation as a victory in "the ongoing war with the enemies of the working class."

"We hope the River Des Peres Yacht Club keeps their word and continues to not allow fascists to organize under their watch," the statement concluded. Then the protesters simply left, positioning the small black sign in the window. The next day, it was gone.

On a recent afternoon, Yacht Club co-owner Cindy Delgado rummages through some shelves in the break room behind the kitchen, finally finding the sign that the Antifa delegation pushed on her in July.

"It seemed like an ambush," she says. "They didn't call and ask for a moment of our time. They just showed up."

By the time the protesters arrived at the deli in person, the Yacht Club had already been slammed with hundreds of comments and an army of one-star reviews accusing the owners of supporting the Proud Boys.

Delgado's husband and fellow co-owner, Michael Sullivan, was working behind the counter with her on the day they showed up in person. "I felt like I was bullied," he says. He is the one who took the sign out of the window.

In retrospect, he admits that he let his feelings get the better of him. In the sign's place, he put up a postcard on which he'd written the words #WalkAway.

The hashtag has gained popularity with conservatives describing their "walk away moment" from the Democratic Party. Sullivan says he was acting out of frustration, and wanted to "ruffle the feathers" of the people he considered bullies, the leftists he felt had wronged him and his business.

"But that just affiliates me with some other thing that I don't know nothing about," he says now, chuckling. He regrets retorting with the hashtag; he soon took that sign down too.

The conflict continued online. The River Des Peres Yacht Club eventually deleted its Facebook page entirely, but not before Delgado lashed out in the comments, arguing that the Proud Boys' "cash was green" and that she didn't want to mix politics with her business. Her retorts were quickly screen-grabbed and used as additional proof that the Yacht Club was defending a "fascist organization."

Scrolling through the archived messages on the now-deleted Facebook page, Delgado finds a message sent to her inbox: "If the Proud Boys are allowed to meet at your establishment, they will be met with massive, violent resistance with no regard for your business."

After getting that, as well as similar messages, Delgado says she called the cops and shut the store for a day. Before all this, she'd never even heard of the Proud Boys, and suddenly she was getting threatened for serving them sandwiches.

But the Antifa group got its way: Delgado and Sullivan asked the Proud Boys to stop coming by, and the Proud Boy on staff left his job there. The group soon moved to Tuckers.

The damage to the deli had already been done. "It really hurt our business bad," Delgado says. Regulars stopped coming by. A neighborhood group moved its meetings to a different restaurant, and Delgado says she had to cut a full-time position and shorten other shifts to compensate for the lack of business. No matter how good the sandwiches, few people want to be connected to a Proud Boy-supporting deli. Delgado estimates that the Facebook posts and protests drove away half of the shop's July and August sales.

For the loss of business, Delgado blames the anti-fascists and Facebook commenters more than the Proud Boys.

Still, she also doesn't want to see any Proud Boys in her deli again. These days, she gets nervous when a group of young guys enter the restaurant. Sometimes, she asks them: Are you a Proud Boy?

Reached by email, the St. Louis Antifa coalition called the Community Power Network refuses to participate in an interview with "entities that give a voice to fascism."

"A desire to see [the Proud Boys] as individuals with a story is a desire to present them as a non-threat," the group says in a lengthy written response. "We will not work to humanize our people's oppressors."

Its message, basically, is don't be fooled. To St. Louis' anti-fascists, the Proud Boys' insistence that they're a harmless men's club that drinks beer and shares right-wing memes is hardly credible.

"The Proud Boys are a violent fascist organization that masquerades as a drinking fraternity," the Antifa group contends. "They are known nationally for harassing and attacking women, immigrants, Muslims and those that oppose their beliefs.... We believe it is not only important, but necessary, to take on fascism at the street level with highly organized and militant tactics."

But as the statement continues, the manifesto slides into socialist theory: The Proud Boys, as a group, are "a cog" within global capitalism, and opposition to the right-wing fraternity is just one more fight to be taken up by the working class.

The statement ends on a revolutionary note: "We must collectively oppose all parasites in our neighborhoods, not just the Proud Boys."

The Proud Boys' opponents aren't just groups with Marxist talking points. There's the Southern Poverty Law Center, or SPLC, whose 2017 description of the Proud Boys as a "general hate group" follows them in every documentary and news article. Twitter also suspended numerous Proud Boy accounts prior to the first anniversary of Charlottesville's Unite the Right rally, for what a spokesman claimed were violations of the company's policy against "violent extremist groups."

Keegan Hankes, a research analyst for the Southern Poverty Law Center's Intelligence Project, says the Proud Boys more than deserve their "hate group" label.

"They end up making comments targeted at immigrants, American Muslims,' Hankes says. "And their founder, Gavin McInnes, openly admits he's an Islamophobe."

McInnes co-founded Vice Media before creating the Proud Boys out of whole cloth — taking the name from "Proud of Your Boy," a saccharine show tune from Broadway's adaption of Aladdin. His persona is a pillar of the SPLC's case against the Proud Boys.

In fact, the organization's report on the Proud Boys is largely a dossier of quotations taken from McInnes' various shows, most recently Get Off My Lawn on the conservative online outlet CRTV. It was McInnes who invented the cereal beat-downs and the group's more esoteric habits, such as the encouragement to stop masturbating, or "no wanks."

Hankes acknowledges that the Proud Boys present a confounding image to outsiders, creating an intentional incoherency of internet memes and inside jokes. But within far-right spheres, he warns, the Proud Boys occupy a unique gray area — giving them a membership ripe for recruitment and infiltration by hard-core supremacists.

"They serve as a gateway for so many people who have gone on to other extremism," Hankes says. "The Proud Boys have kicked some of these extreme figures out, and they have let others stay, either out of ignorance or out of willful ignorance."

Hankes mentions that Unite the Right organizer Jason Kessler was a second-degree Proud Boy before his excommunication, and that the Proud Boys' most revered text, Pat Buchanan's Death of the West, is a thinly veiled treatise on danger posed by demographics shifting toward minorities rather than those of European descent.

"The basic argument of that book is that the decline of white birth rates is leading to the death of Western civilization," Hankes says. Similarly, he says, the Proud Boys' noble talk of defending "Western civilization" is both a simplification and a smoke screen.

Further muddying the waters is the Proud Boys' tendency to borrow imagery from quasi-white-nationalist sources: The Fred Perry shirts favored by the Proud Boys were first adopted by mod culture in the 1960s, then taken up by skinheads and later claimed by explicitly anti-Nazi punk bands. (Last year, a Fred Perry spokesman told the Washington Post that the Proud Boys are "counter to our beliefs and the people we work with.")

And then there's the "OK" hand gesture Lasater flashed during his first-degree initiation. According to the fact-checking website Snopes, the gesture was intentionally appropriated in 2017 by trolls hoping to create a "hoax" white-supremacist symbol to enrage liberals. Now the gesture has a life of its own, embraced by an assortment of right-wing personalities and Trump supporters. (Twitter erupted during Brett Kavanaugh's confirmation hearing when an aide appeared to flash it.) A St. Louis trainer who marched with white supremacists in Charlottesville was captured in photos making the same gesture.

But even as their jumble of borrowed ideas and symbols brings them into conflict with the left, the Proud Boys' ongoing battles with Antifa have led them to comity with hate groups on the right.

"The Proud Boys constantly look to seek out the sense of victimhood; they thrive off conflict and controversy," Hankes points out.

Right Wing Leaks, the group that successfully infiltrated the Missouri Proud Boys Facebook group, has its own theory on what's driving the Proud Boys. In a phone interview, a representative (who declines to give his name) argues that the group is offering something its angsty, Trump-supporting members thirst for.

"They're like lost boys," he suggests. "The Proud Boys' ideas don't challenge these men to think critically about any of their behavior or choices. It's just reassuring to be told, 'You've been right all along.'"

Four weeks after karaoke night at Tuckers, the St. Louis Proud Boys convene at a house in St. Louis County. They've got cans of Budweiser and an Imo's Pizza, and a YouTube compilation of Trump's 2016 election-night win is streaming on the TV. It makes one Proud Boy nearly tear up.

"We saved the world, you guys, can you believe it?" one says. "We saved the fucking world."

Outside, on a porch ringed by Tiki torches, the local chapter's vice president is smoking the first of many cigarettes. (He spoke on the condition that he not be named in this story.)

"I just wanted to make a platform for people of a conservative mindset, a place where they felt welcome and not ostracized," he says.

The St. Louis Proud Boys' alienation is a frequent conversational topic, almost always in relation to their support of Trump.

"I thought this election was going to be like any other," says Lasater. "I thought everyone was going to be at each other's throats until Election Day, and then somebody wins and we all just accept it."

That didn't happen. In St. Louis, being outspoken boosters of the Trump presidency damaged the Western chauvinists' relationships and ended jobs. One Proud Boy remarks that he grew up liberal and voted for Obama, but claims his co-workers turned on him "the second I made an original thought for once in my life."

"I wasn't saying anything that's racist, I wasn't saying anything that's bigotry, I'm just having my own opinion," he says. "I lost a lot of friends, I lost a lot of people, just speaking up."

To replace those lost relationships, the Proud Boys have turned to the profane approval of their Virgil, Gavin McInnes. It's McInnes' ability to convey self-help lessons and elaborately offensive comedic riffs — jokes that often make Muslims, feminists and gay people the punch line — that seem to most captivate his fans. Somehow, the author of How to Piss in Public has become a compass for young men searching for a guide in the wilderness. (On McInnes, Lasater later attempts to distance himself, saying, "He's our founder, not our leader.")

For members, it's easy to get swept up in Proud Boy self-righteousness, to let the frustration boil over. Last year, Lasater took to Facebook during the protests that followed the acquittal of ex-St. Louis cop Jason Stockley.

Lasater wrote: "While you were protesting in the sweltering heat, I was enjoying air conditioning, a three-course meal and shaking Steve Bannon's hand."

Bannon, the strategist credited for encouraging Trump's Muslim Ban and bringing the alt-right into the mainstream, is a widely reviled figure for supporting what many suspect is a quiet white nationalism masquerading as "civic nationalism" (a term Lasater himself uses when describing his own views).

Some of Lasater's Facebook friends did not take well to the trollish Bannon-praising Facebook post, with one simply remarking, "Congrats on being a turd, I guess?!?"

But within the Proud Boys, nationalism doesn't make you a turd, and there's nothing wrong with voting for Trump or shaking the hand of Steve Bannon. Doing these things, the Proud Boys insist, is part of a proud American tradition.

"What's wrong with nationalism?" the chapter's vice president posits at one point during their gathering, his voice rising with exasperation. "What's wrong with being a patriot? That's what got us to the moon. It's America. What's wrong with that? Who does that hurt? Who does that hurt?"

"Nationalist," though, isn't the label the Proud Boys struggle to reject. It's "Nazi." It's Jason Kessler and his Tiki torch-wielding crowd of young men chanting "Jews will not replace us." It's Gavin McInnes riffing on the idiocy of feminism or extolling the accomplishments of white people and "Western civilization."

Again and again, Lasater, Rohlfing and other St. Louis Proud Boys wave off these associations. Their nationalism isn't race-based, they insist. But there are open fascists out there, and some of them do find their way to the Proud Boys. Lasater recalls one applicant to the St. Louis group who bought a Fred Perry polo and provided a first-degree initiation video before revealing that he represented the American Blackshirt Party, a group that seeks to create "the foundations of a Fascist America." He was summarily rejected, Lasater says. Same with a Missouri man with neo-Nazi tattoos who appeared in photos uncovered by Right Wing Leaks.

Anyone can make a video of themselves stating the Proud Boy oath. Anyone can buy a $90 shirt or show up to a rally. Rohlfing wonders aloud what would happen if the Proud Boys staged a gathering in St. Louis. What if white supremacists decided to attend?

"How do we know if they are white supremacists?" he asks. "Are they going to show up wearing SS uniforms?"

For the Proud Boys, efforts at culling their ranks only seem to dig them deeper. On multiple occasions, McInnes has ordered the Proud Boys to avoid certain rallies (including 2017's Unite the Right catastrophe), in an attempt to break the association with groups that vocally praise Western civilization in terms of race and superiority. Still, some Proud Boys show up. Or, if not Proud Boys themselves, then friends of Proud Boys, or former members, or Facebook acquaintances in right-wing groups with photos revealing neo-Nazi tattoos.

Of course, those are the associations that draw Antifa, who see only a battalion of black-clad fascists. Yet Rohlfing argues it's Antifa that's drawing out the real fascists.

"The main reason these [white supremacists] show up to these events is because Antifa is there," he says. "If Antifa spent their time attacking actual fascists, white supremacists and Nazis, we'd —"

Lasater cuts in. "We'd work together on it, for fuck's sake," he says.

After a couple hours at Lasater's, the Proud Boys decide to finish their "boys night" in St. Charles. Their black polos are tucked in tight (they shrink in the wash, one explains) and they roll into a nightclub looking every bit the Western chauvinists. But outside their closed Facebook groups and Portland rallies, these prideful patriots seem out of place, even in the Trump country that is St. Charles. They sit at a circular table at the edge of a dance floor, looking like uniformed busboys at someone else's prom. One Proud Boy attempts chatting up several women, to no avail.

So they gather at the edge of the dance floor, watching the action amid the lasers and smoke. They talk about an upcoming gala in Las Vegas, "West Fest." It's expected to attract hundreds of Proud Boys. "It's going to be awesome," says Rohlfing.

And for the St. Louis Proud Boys, it is. Lasater finally gets that third degree: a Proud Boy tattoo emblazoned on his forearm. Rohlfing will later post photos from the gathering on Twitter, one showing dozens of Proud Boys in a group pose, many using one hand to flash an "OK" hand gesture while grasping a drink in the other.

There, finally away from Antifa, one imagines the Proud Boys are free to be themselves, to pursue happiness, even if all that means is not being criticized for being too chummy with Nazis. Just a men's group. A drinking club. A fraternity. Anything, really, as long as it's not an apology.