When Michael "Big Mike" Aguirre took a trip to the Caribbean in March, he figured he'd probably stay for ten days or so, tops. A soul and R&B artist, guitarist and bandleader who, alongside his Blu City All Stars, serves as a staple of St. Louis' thriving blues scene, Aguirre was slated to perform at the 30th annual Moonsplash Reggae Festival on the tiny island of Anguilla, just east of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. The long-running event, organized by Anguilla reggae artist and cultural ambassador Bankie Banx, was set to run March 12 through 15; Aguirre, who has made multiple tour runs through the Caribbean in recent years, figured he'd do the show, visit friends on the nearby island of St. Thomas and then head home to St. Louis. COVID-19 had other plans.

As the novel coronavirus made its way around the world, it brought travel restrictions with it. By March 17, it had become clear to Aguirre that trying to hop on an airplane would be a nightmare, so he and his partner Kristin Babcock, herself a St. Louis scene staple as general manager of BB's Jazz, Blues & Soups, decided they'd be better off staying put for a while.

"We figured, let's wait and see two weeks, see what happens, because we don't really know what we're dealing with yet," Aguirre says of the decision. "And also I didn't have a whole lot of confidence in the [Trump] administration's ability to successfully navigate through that.

"That seems to have been good instincts," he adds with a laugh. Those two weeks have turned into nine months. Within days of the music festival, leaving the island ceased to even be an option. Anguilla officials closed its airport and seaport on March 20. The ferry that shuttles visitors to nearby St. Martin, where there is a commercial airfield, left that weekend with no date for its return. The territory was officially locked down, with no one able to come or go, by air or by boat.

Further measures to combat the spread of the virus were soon implemented as well. The government instituted a shelter-in-place order, allowing restaurants to operate as carry-out only and limiting the size of public gatherings to no more than twelve people. On March 26, the island saw its first cases of COVID-19 — one a 27-year-old American woman and the other a 47-year-old Anguilla resident who had been in close contact with her. They were quickly identified and separated from the rest of the population.

"So they were in quarantine. They got better, and then at that point protocols were put in place where you couldn't get in," Aguirre explains. "Some people might try to sneak in on a raft, but they had shore patrols and boats. No boats were allowed to come up, no flights coming in, no ferries coming in."

The measures worked. To date, Anguilla, with a population of about 15,000 people and a footprint of just 35 square miles, has seen no community spread of the virus. As of the time of this writing there have only been ten total confirmed cases — none of them fatal.

"So they managed to put a lid on it," Aguirre says.

Meanwhile, the situation in the United States went haywire fast. Charitably speaking, it could best be described as an unmitigated shitshow, with more than 350,000 dead amid uncontrolled spread while elected officials on both sides of the aisle and at all levels of government have abdicated responsibility of any kind. Citizens are at each other's throats in the absence of any true leadership, and large swaths of the population have outright labeled the illness a hoax. As a result, hospitals are filling to capacity, and lockdown orders remain in place across much of the country.

Looking at it from an outside perspective, Aguirre is befuddled.

"I don't know what words to use to describe whatever the fuck just happened in the States over the last nine months," he says. "Other than a guy trying to win an election and he didn't, so it was all just a big waste in the way we handled it."

In light of all that, even when Anguilla did open up for travel again, and Babcock headed back to St. Louis in October to attend to familial obligations, Aguirre decided it best to just stay put. Instead of dealing with anti-maskers and sickness and economic ruin, he's in limbo on an island paradise with 33 beaches and no COVID-19 to speak of.

"Literally, of all of the places in the world, including St. Louis, this was beyond fortunate to wind up here," Aguirre muses. "Almost like it was no mistake."

Part of Aguirre's ability to make due on the island comes through the connections he made on previous trips through the region. Aguirre took his first tour through the Caribbean at the end of 2016, accompanying fellow St. Louis scene stalwart Hudson Harkins, drummer and bandleader of Hudson and the Hoo Doo Cats, on a three-week run through the Virgin Islands.

"He's been going down to the V.I. for maybe 25, 26 years," Aguirre says. "And we were out at the Beale on Broadway one afternoon after a gig or something, drinking beers. And I said, 'Are you still doing that run?' And he said, 'Yeah, I'm thinking about one more.' And I'm like, 'Fuck it, take me with you. I'll carry everything heavy, I won't complain,' you know. He's like, 'It's a three-week run.' I'm like, 'Perfect, sounds good, sign me up. Won't even charge a rate; let's just get it done.'"

Aguirre and Hawkins tapped Andy Coco, a KDHX DJ and bassist who has put time in for a number of local acts over the years, including the Street Fighting Band and Aguirre's Blu City All Stars, and the three set out as a trio performing on the islands of St. Thomas, St. Croix, St. John and Tortola as the Hudson Hoodoo All Stars. At the end of that run, Aguirre sat down with Hawkins' booking agent and inquired about setting up another string of shows in the spring, but he was told that things were all booked up and he should try making a trip in the fall.

"Which, hindsight shows would have been after [Hurricane] Irma rolled through here and busted everything up — it wouldn't have been a possibility," he says. Undeterred, Aguirre got a run of shows put together for March 2017, bringing Coco and fellow St. Louis musicians Nathan Hershey and Tony Barbata along to accompany him, performing as Big Mike and the Blu City All Stars. "I put my head together, called some friends and lined up like a week's worth of shows in the V.I.," Aguirre says. "Came down for a week, had that Tuesday and Wednesday off, and just sent a Hail Mary request to the place I'd been in Tortola called Myetts and said, 'Hey, could you give the band a work permit, a gig, a room, some dinner — some combination of those things?' And they totally hooked it up."

That particular gig would prove to be a consequential one. In attendance that night was one Bankie Banx, organizer of Anguilla's Moonsplash Reggae Festival and owner of the bar where it takes place each year, the Dune Preserve.

"Normally, after all of these Moonsplashes, after all of the production that takes a month or two or even longer, he'll get on a boat and sail to a different island and go visit friends or this or that," Aguirre says. "So he happened to be in Tortola the night we played — this St. Louis band playing all this R&B and soul stuff. And he liked it, invited me for breakfast in the morning, and we chatted." A few months after that, on July 5, 2017, Banx flew Aguirre and Coco, who teamed up with yet more St. Louis musicians, Kevin O'Conner and Elliot Sowell, down to perform at the inaugural Rendezvous Bay Folk and Blues Fest, which Aguirre describes as "a little whirlwind four-day trip at the Dune Preserve."

Aguirre would go on to forge a tidy working partnership with Banx, and he flew down solo in June 2019 to perform at the Rendezvous Bay Folk and Blues Fest again, followed by an eighteen-day solo stay in Anguilla running from December 2019 to January 2020. It makes sense, then, that he was invited to play at this year's Moonsplash in March, which is what got him where he is today.

When Moonsplash wrapped up, most of the musicians who'd flown in beat a hasty retreat as COVID-19 travel restrictions loomed. But Aguirre, knowing he had a friend in Banx, figured he might as well stick around.

Banx, naturally, is a musician as well — a performer known to some as the "Anguillan Bob Dylan." Born Clement Ashley Banks, Banx has been playing music since 1963, when he built his first guitar at the age of ten. He's regarded as a pioneer of reggae music in the east Caribbean, and his career included years of touring through Europe and the East Coast in the '80s. Since 1991, he's hosted the Moonsplash Festival each year and has brought artists including Toots & the Maytals, Black Uhuru, Jimmy Buffett, the Wailers, Inner Circle and countless more to the Dune Preserve stage.

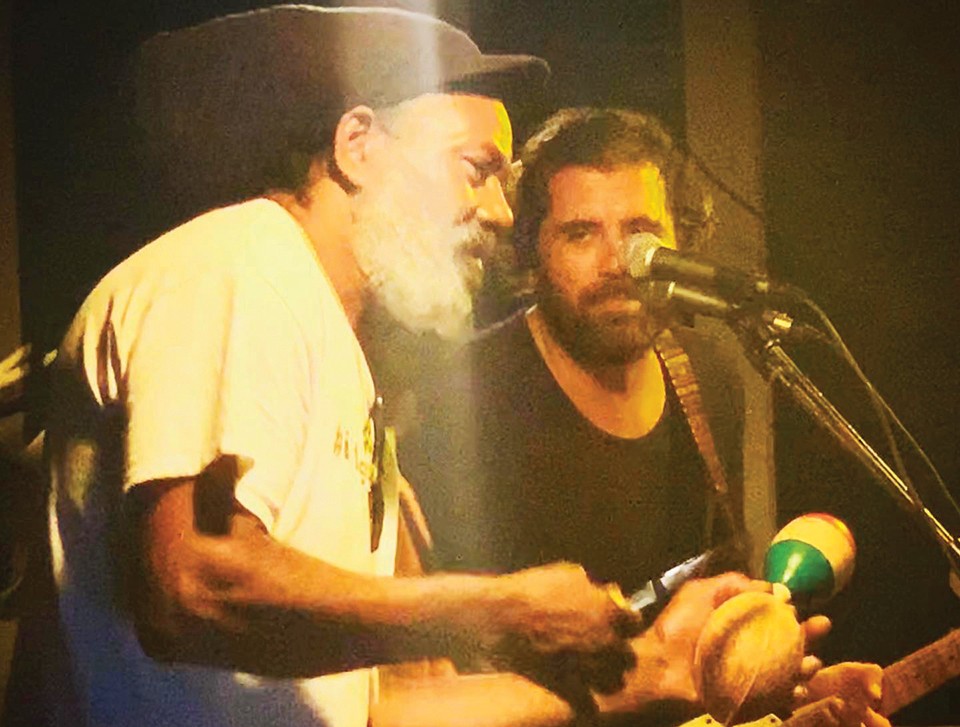

When the island went into lockdown, Aguirre and Banx joined forces, with the former providing musical accompaniment — as well as a little technical know-how — for the latter.

"Bankie's an old dinosaur; he doesn't know what Facebook Live is, streaming, and none of us has faced a situation where all the gigs go away and the whole industry goes away," Aguirre explains. "So I teamed up with him to show him how to do livestreams down at the Dune Preserve. You know, pick up a guitar, do Facebook Live, play a song and then post it up there, and then people — someone says, here's five dollars, here's ten, here's twenty, here's this or that. So it was an opportunity to pivot to an online stream using a cellphone — because that's all I packed for in a week — and the Dune Preserve is a venue that was locked down, but we could just stream and tell all these stories about Bankie, who's basically an ambassador of this island and an amazing artist in his own right who built the place."

The endeavor has proven surprisingly successful, Aguirre says, with the pair regularly streaming performances on facebook.com/DunepreserveAI while encouraging tips.

"The amazing thing is St. Louis was so supportive through Venmo and PayPal and stuff. It really revolutionized everything," he says. "People might spend $100 to go see the band play one night, and $80 of that is on food and maybe $20 is for the ticket, for five or seven people to split. But then you stream and someone's like, 'Hey this is a crazy situation; here's $500 on Venmo.' And it could be $5 — it's been diminishing returns after eight months. But St. Louis has been so supportive. And not only that, the people that I've met here, from streaming with Bankie.

"It's just a direct medium from the artist to — really, this is mostly friends and family, because I'm not a big shot — but just people that I'm able to be in touch with, thanks to a cellphone and Wi-Fi."

At present, Aguirre has no clue when he'll return to St. Louis -- though coming home is certainly never far from the front of his mind.

"Let me just say this: The last thing I want to do is seem like I'm thumbing my nose at everybody at home," he says. "Yes, this is paradise. Yes, I've gained more than I can describe in perspective since I've been here. At the same time, this has been the most challenging experience of my life."

His lease for his downtown apartment ran out in July — he had to arrange for his belongings to be packed up and put into storage. It didn't make sense for him to renew that lease, he figured, especially since he's now spending what little he brings in on a place in Anguilla.

"Without any income, having to come up with rent here for a little apartment, one bedroom, one bath, no hot water, no drinkable water — pretty awesome," he laughs. "And then the rent on the lease back home? So I'm pretty much homeless in St. Louis at this point until I can generate enough income to pay for rent somewhere. Staying with friends and family isn't the best idea when cases are blowing up all over the place."

Considering the fact Aguirre is a full-time musician and opportunities in that field have all but dried up in St. Louis as well as the United States at large, it just doesn't make sense to come home at this point, he says. He also knows that many of his colleagues are struggling just to get by.

"I don't wanna be part of that problem and be there competing with them for limited scraps," he says. "It was hard to be sustainable before, working with local industries and stuff, as a musician. So not being part of the problem — and not putting anybody at risk — sounds like a good idea, and that's guided my thinking."

Aguirre's career plans are in something of a holding pattern now as well. He'd finished recording his debut album, Mississippi Stew, before leaving for Anguilla, with tracking done over two years' time at Sawhorse, Native Sound and Red Pill studios. He says that album is twenty years in the making, encapsulating all of the time he's spent on stages in St. Louis. He's excited to get it out into the world, but he also knows it would be somewhat pointless to release now, when touring to support it is impossible. "It costs money to secure the rights to everything to duplicate, and there's just no revenue coming in," he explains.

In some ways, though, his experience in Anguilla — and especially performing with Banx — is reminiscent of his early days in St. Louis' music scene, where he spent his time learning from some of the best and brightest blues musicians ever to step foot on a St. Louis stage.

"I was born in 1980," Aguirre says. "Too young to ever get to know Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, Chuck Berry, Albert King, all the legends. But before I turned twenty in 2000, I met Big George Brock, Boo Boo Davis, Blues Boy Bubba, Oliver Sain, Bennie Smith, and was immersed on their stages and in their communities, from Alorton to Wellston."

That time, Aguirre explains, was formative for the young musician, cementing his love of the blues and setting him on a career trajectory that he's stuck with for two decades. His time spent on the island, too, he sees as revelatory.

"Twenty years later, from the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, I found myself once again fully immersed in a community, a culture, and nation unlike my own, and once again I was welcomed by family, this time by Bankie Banx," he says. "After twenty years of training as a performer, vocalist, bandleader and small business owner in St. Louis, I was unexpectedly granted the opportunity to live, eat and learn from one of the most inspiring persons I've come across in a life dedicated to music and spirit."

The Dune Preserve, too, is a place where Aguirre has found inspiration — and one that he describes in uniquely St. Louisan terms as "the union of the best aspects of the Venice Cafe, Beale on Broadway and Blues City Deli, on a beautiful beach on a beautiful island full of 15,000 beautiful people who go out of their way to be nice to each other all the time."

Even before he became something of a castaway on the island, Aguirre had hoped to create more connections between Anguilla and St. Louis. Part of the reason Babcock, general manager at BB's, had come with him in the first place was so that they could network together and try to build bridges between the music scenes in the two locales.

"As a career goal I've always wanted to bring people — musicians and also music fans and the people who make the scene and the vibe so great — out of St. Louis and hang out with them, you know?" he says. "After fifteen years spending more time onstage at the Beale on Broadway than I did in bed, it's cool to have the same people in a change of scenery. So that's kind of what I'm trying to work on." For the time being, that's something of an unrealistic goal. St. Louis is still in the throes of a pandemic, with hospitals overflowing and a virus spreading unabated. Aguirre, by contrast, might as well be on another planet — one with plenty of sea and sunshine and surprisingly little sickness. Until matters sort themselves out, it's unlikely that Aguirre's dream of a St. Louis-Anguilla connection sees fruition.

"I'm in this weird paradise bubble trying to hold the door open as long as I can for people to come see what it's about," he laughs.

But meanwhile, rather than focus on the long term, Aguirre is set on doing what he can in the here and now.

"[I'm going to] listen and learn from everyone here who knows more about Caribbean music than I do, which is everyone," he says.

"My job," he adds, "is bringing the STL vibe wherever I go."

"Big Mike" Aguirre & the Blu City All Stars have copious new material due in 2021, including their debut studio album, Mississippi Stew. Follow Aguirre's island adventures (and maybe drop some virtual bills in the virtual bucket) at bigmikestl.com or facebook.com/DunepreserveAI.