Malachi Duncan slips out of a dark corner of the community college theater and onto the stage.

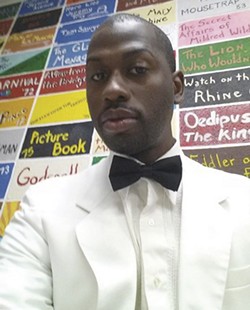

He is in full costume. A white jacket fits crisply over his skinny, six-foot-two frame. A matching white shirt and black bow tie add to the formal air of the butler's uniform.

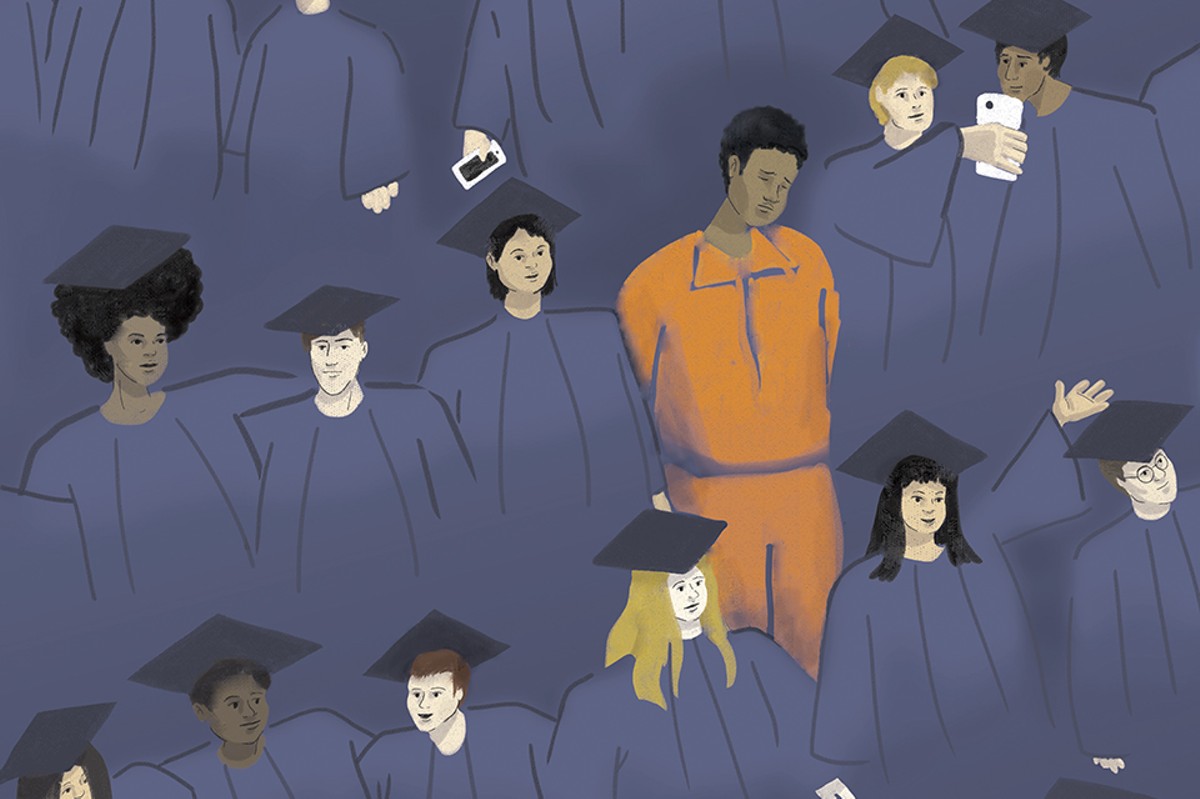

The play is Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, a tale of desperation and deceit within a family of schemers. The main characters are complex and intriguing, but Duncan does not have one of those roles. He plays Lacey, a black servant who, in some adaptations of Tennessee Williams' drama, is reduced to an unseen voice piped in from off stage. His job is to prop up the main players, serve as an under-drawn reminder of the family's casual racism.

"I'm coming!" he cries and hurries across the stage during possibly his most dynamic scene. "I'm coming!"

Appearing here, even in a limited role, seems like a crazy risk in retrospect. Duncan should be lying low. He enrolled at Jefferson College for the 2013-14 school year using the name of a friend with whom he is sharing his ill-gotten financial aid checks. He wrote the friend's social security number on the applications and will use it to set up bank accounts, obtain a fraudulent driver's license and even get a job at a campus day care.

These are federal crimes, and he could be exposed with a minimal amount of scrutiny. But here he is, literally stepping into the spotlight, conducting a performance within a performance.

Duncan is friendly with the other actors but not close. He has felt like an outsider his entire life, and he does not have much in common with the rest of the cast. They all come from placid small towns within twenty miles of the college's Hillsboro campus. Duncan grew up in East St. Louis, raised primarily by foster parents as a protection against a mother whose history of neglect and abuse made national news before he was even born. Even today, people of a certain age in his hometown trace his lineage to one of the worst tragedies the city has ever seen.

In Hillsboro, they don't even know his real name.

The production of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof ends after a four-show run in October 2013. Duncan auditions for the next semester's show but is not cast.

Michael Booker, the college's division chair of fine arts, remembers only the barest of details about him. An experienced actor himself, Booker played the role of Big Daddy, a dying patriarch whose duplicitous children are trying to undercut each other as they compete for his fortune.

"I'm very proud of the quality of the show," Booker says in an email. "We had a strong cast."

Duncan seemed to have little experience, but that's where a lot of students begin, Booker says. One of Booker's favorite things about performing with the college's theater department is seeing newcomers grow into larger, more complex roles through the course of several plays. But he never worked with Duncan again. He never really had any cause to think about him again until more than two years later when visitors arrived on campus.

"I can assure you that we were all shocked when [federal agents] came by asking about him," Booker says. "We had no reason to think that he was involved with the crimes he's been accused of."

A college spokesman says they have seen cases of fraud before. Students are granted financial aid and never show up to campus, or they drop out after a couple of weeks and pocket the loan checks. Duncan's situation was different. He studied English and worked at the day care. After living off campus with his friend for his first semester, he moved into one of the college's dorms, just up the hill from the theater. If anything, Duncan was trying to embed himself even further into the college life.

"He wanted to play the part, if you will, of being a student," says Roger Barrentine, the college's director of public relations. "Eventually, his deeds caught up with him."

Technically, it was the U.S. Marshals who caught up with Duncan.

The Justice Department's human bloodhounds had been searching more than a year before they cornered Duncan in front of a Tennessee apartment complex. They missed him in Indiana, where agents arrested the friend who'd lent Duncan his identity, and in Mississippi, where he contemplated turning himself in.

By the time they found him in March, he was in his third semester at the University of Memphis, enrolled under the name of his youngest sister's boyfriend. It was one of more than a dozen colleges he attended over a fifteen-year period, using at least three different identities in the process. The financial aid he obtained under his own name was no crime, but federal prosecutors say he ran up a bill of more than $50,000 with the U.S. Department of Education while masquerading as others.

Duncan remembers it was raining the morning of his arrest, and the deputy Marshals had brought with them a fifteen-year-old photo to aid in identification. After brief stops at jails in Tennessee and Oklahoma, they hauled him back to Missouri, where he spent the better part of a year in the Ste. Genevieve County Detention Center, about an hour south of St. Louis.

"I never wanted to be back in here, ever," Duncan says. "I was doing everything I could."

By "here," he means any jail anywhere. He had been locked up multiple times in the past on small-time fraud cases and probation violations, but never for more than a month or so.

Now he is 33, and more than four years have passed since he took the stage at Jefferson College. He wears a Ste. Genevieve County orange jumpsuit, the graying sleeves of a once-white long-underwear shirt stretching toward his thin wrists and long fingers.

He was sentenced in November to three years and nine months in prison after pleading guilty to federal charges of student loan fraud and aggravated identity theft stemming from his time at Jefferson College. Prosecutors say he conspired with his friend to falsely obtain federal financial aid, enroll in classes, apply for student housing and land a campus job. His sentence includes a demand for $57,139 in restitution, which includes $2,000 to the state of Tennessee and $4,529 for a fraudently paid car repair. It might as well be $57 million in light of Duncan's ability to pay it all back.

Someday soon, the Bureau of Prisons will ship him to one of the federal holding facilities it has scattered across the country. Duncan does not know when or where. He tries not to think too far into the future when it comes to things like that.

The past can be a little hazy, too, he says. Suppressing old memories of abuse makes it easier to handle the daily life: "I try to put things in the back of my mind."

But he remembers the play. It was his therapist's idea, he says. He should try doing something fun that was just for himself, she suggested. He had always wanted to be a filmmaker and had done a little acting and writing in high school. When he saw there were open auditions for Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, he decided to try out.

"It felt good," Duncan says, his nose wrinkling as he smiles. "I hate to say this, but it felt normal. I don't get a lot of chances to do things that a lot of normal people do — things that normal college students do."

A normal life would have been a small miracle for Duncan.

He is one of Virginia Williams' eighteen children and one of seven who are still alive. He was born three years after a fire torched the family's two-story East St. Louis house and killed eleven of the kids who would have been his older brothers and sisters.

Newspaper stories about the January 11, 1981, tragedy described a blaze that burned with such violence that frantic neighbors and firefighters had no hope of reaching the children, who ranged in age from ten months to eleven years old.

"By then, there was still a little screaming, and I heard what sounded like footsteps," a neighbor told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in the aftermath. "But the fire was too bad and no one came out. By that time, there was no way to get them out."

At the time, Williams had twelve kids. The oldest, who was living with relatives in Mississippi, was the only one left. Williams had left the children alone for hours while she was out gambling with her boyfriend, Will Arthur Jones, who was the father of seven of the dead kids. The doomed siblings suffocated in the smoke.

Nearly 40 years later, the funeral photos of eleven little white caskets arranged side by side are as heart-wrenching as ever.

Williams ultimately pleaded guilty to neglect. A merciful judge, concluding that she had endured enough, sentenced her to a year probation. Williams was pregnant at the time with the first of six children she would give birth to after the fire. Duncan was the youngest of four boys, followed by two sisters.

"I don't know that she's mentally able to really comprehend the effect she's had on us," Duncan says of his mother. "I believe in her mind, she did what she thinks is best."

Williams had a gambling problem and a history of mental illness. Even before the fire, she had been investigated by child welfare agencies, and the horrors of losing eleven of her first twelve children only made things worse.

Duncan avoided the worst of it for years; shortly before his first birthday, he was placed with foster parents. A few months later, in 1985, Williams was sentenced to prison in Illinois for child abuse, records show. When Duncan mentions his "mom" and "dad," he is speaking about Alice and Willie Duncan. Born Matthew Jones, he took their name when he turned eighteen. Alice Duncan still remembers when he asked what she would have named her son if she'd had another boy. "Malachi," she answered, thinking little of it. He changed his name the same day.

But Duncan's life with Alice and Willie was marred by lengthy interruptions. The state of Illinois was eager to reunite foster kids with their biological families, and so Duncan started visiting his mother's home on weekends when he was eight or nine. He remembers his father beating his mother on his first night in the house. The culture of violence and abuse in his mother's home was a shock to him.

"It was bad then, but it got worse when I eventually moved in with her," he says.

By the time he was ten, he was living with his biological mother full time. He remembers her whipping him and his brothers with an air conditioner's cord, punching and stomping on them. She would erupt over minor offenses or just a bad night gambling.

"Me and my youngest brother, we were getting beat so much we didn't think we would survive," Duncan says.

They eventually plotted to poison her to death by mixing boric acid into her coffee creamer, he says. "I had it in my head, if we didn't get rid of her, she was going to get rid of us."

The scheme backfired when she discovered the toxic concoction and forced Duncan to eat it, he says. He got sick but survived. Williams declined through a daughter to be interviewed for this story, but she discussed the poisoning incident with a Post-Dispatch reporter in 2001.

"I don't remember," she told the paper. "Maybe that's true... I could have. I probably did to see if [the boys were telling the truth]."

She admitted that she was rough with her boys.

"I whipped them with whatever I got my hands on," she said in the interview. "I didn't want them to come up like me, poor, uneducated and living on the state."

The Post-Dispatch story, which came twenty years after the deadly fire, detailed years of abuse and the toll it had taken on Duncan's brothers, who had lived with her much of their lives. Duncan, however, had returned to the home of his foster parents and, as the story told it, seemed to have escaped their fate.

"Of the four sons, only [Duncan] appears to have emerged relatively unscathed," the paper wrote. "Except for a brief, tumultuous stint with Williams, [Duncan] has lived nearly all of his life in the same foster home, where, he said, he has received guidance, discipline and support. He is a straight-A student with aspirations of going to Yale University."

Duncan just likes school. As a child, along with the physical abuse and mental abuse, he says he was sexually abused, although he refuses to discuss that in detail. Even during the worst days, he could find a refuge in the classroom.

Linda Lawson first noticed him while working as a substitute teacher at George Rogers Clark Junior High School, now a burned-out shell on State Street in East St. Louis. He stood out because he was well-mannered and smart, but he also seemed to be by himself.

"He felt comfortable around adults, because he was an outsider," Lawson remembers. "He was in a rough-and-tumble area. There was something that made me want to help him or protect him."

At the time, she did not know much about his background, other than he was a foster child and the other kids would pick on him. When she asked him why he did not fight back, he replied, "I'm going to let God fight my battles."

Other teachers also recognized something in the skinny boy and gently guided him toward after-school writing programs, where he began to work on stories and plays. He loved fantasies most of all — superheroes and Star Wars — but also tales about kids with seemingly normal lives.

Deborah Granger, an East St. Louis native who now publishes an arts magazine in Los Angeles, returned to her hometown for a couple years in the early 2000s and spearheaded the Miles Davis Arts Festival in honor of the 75th birthday of the city's famous son. While she was in town, Granger helped teach one of the writing programs that had become Duncan's outlet. She lost contact with him in the years that followed. Her voice softens when she learns he is in jail.

"He was a very talented young man," she says, later adding, "That's so sad."

Alice and Willie Duncan still wonder how exactly his path has led to prison.

"As a kid, I never had a problem out of him," Alice Duncan says. "That's why I can't understand."

He spent most of his time in his room reading or watching movies. He tried writing some of his superhero fantasies and made a short film recorded on VHS.

The Duncans, both in their 80s now, fostered 42 children over 34 years by their count. Some stayed only briefly, others for years. Willie Duncan worked as a laborer for Midwest Rubber, and Alice Duncan did a little of everything from warehouse work to selling Avon and caring for senior citizens. It was a solid, middle-class life with occasional vacations. Once, when Duncan was still a young teen, they even went to Disneyland.

Duncan recalls his years in their house as the best in his life, but he grew more rebellious as he reached his later teens. He eventually moved out. During a low point, he stole $8,000 from his foster parents. He says now that he had reconnected with his biological mother and younger sisters and had begun writing bad checks; he says he was trying to help cover the bills. The Duncans were hurt but ultimately forgave him.

"[Alice Duncan] knew what kind of person I was," he says. "She was mostly upset that I hadn't told her what was going on."

In the end, the incident seemed like a lapse from which Duncan would learn a lesson. He had a stroke of luck when his old teacher reached out to him. Lawson had read the Post-Dispatch story about Williams' children after the fire and realized for the first time he was one of those kids.

Lawson had worked with East St. Louis Mayor Carl Officer, and so she connected the two.

Officer hired Duncan at his family's funeral home and was so impressed with his sharp, young employee that he helped him win a full scholarship to Talladega College, a historically black college in Alabama.

But Duncan left Talladega after a few months. He says now he was homesick.

Everyone who knew Duncan as a kid had thought he managed to escape his mother's legacy unscathed, but Lawson says she now realizes that was not the case.

"It's just been a sad situation," she says. "In some ways, the lives of [Duncan] and his brothers were as destroyed as the ones she buried."

Duncan racked up a few convictions for writing bad checks after dropping out of Talladega. It was the beginning of snowballing legal and financial troubles. "Trying to stretch a dollar is what I was doing," he says.

He wrote bad checks to his dentist, the eye doctor and his landlord for rent. One of his first, in March 2010, was for $279.58 worth of groceries at a Schnucks in Illinois.

They were a string of short-term solutions, and they led to lasting problems. It was not long before his criminal record made it impossible to find a job, he says. Duncan had worked for nonprofit social work organizations, using his experience to counsel kids from rough backgrounds. But those avenues were drying up, and even low-level jobs in restaurants had begun to seem out of reach. So he made a deal with an old friend from the East Side named DeMarcus Brewster.

Brewster had his own problems growing up, and he had lived with Duncan off and on when he got older and had nowhere to go.

Duncan claims he hatched the plan after he returned home from one of his bouts in jail and found his possessions had been stolen. He blamed Brewster and says they worked out an arrangement to settle up.

"I said, 'DeMarcus, look, you owe money. I will work under your name. I will give you half the money, and you can stay with me for free,'" Duncan recalls.

Duncan had continued to pursue college after Talladega, but he was running into problems there, too. Arrests and jail time meant missing classes and often dropping out all together as bounced from one school to another. A probation investigator would later count five colleges and trade schools Duncan had to abandon because of repeated jailings.

He says he wrote his first bad checks to help his younger sister with groceries, and when his biological mother found out, she urged him to write more for cash. To this day, he says he does not know how many he wrote over the years. He did it recklessly, willing the consequences from his mind even as he wrote bad checks to pay court fines for writing bad checks. He was smart enough to know he would get caught but did not see much hope for anything better.

"One might think well as many times as I been locked up how do I get by?" he muses in a letter. "Well I don't."

The bad checks kept popping up like tiny landmines he had buried and temporarily forgotten. All it took was a pissed-off creditor to call the cops. "In my head, I thought I could put the money back, but I kept getting farther and farther behind," he says.

Making things even harder, he had cases on both sides of the Mississippi River. At one one point, his foster parents cashed out bonds they'd saved for his college tuition to settle a case in St. Louis, only to see him delivered directly to jail in Illinois for violating probation, he says. If he was supposed to be staying in Missouri, he was in violation for going home to Illinois, records show. And each time he was locked up, he risked losing whatever job he had managed to get.

"I was trying so hard to turn my life around, and I realized I couldn't do it," he says. "I never was going to make enough money."

Hillsboro seemed like a place where he could escape, at least for a while.

He and Brewster got an apartment together, using the money from student financial aid and whatever Duncan could make working to cover their bills. Duncan went to class and Brewster had a free place to live. Later, they repeated the process in Indiana. Duncan had been convicted in 2015 for writing a bad check in Illinois and sentenced to eighteen months behind bars. Instead of reporting to prison as ordered, he moved to Indianapolis where he rented a place in Brewster's name, worked as an Uber driver and enrolled in a trade school.

But in early 2016, Duncan was tipped off by a notice from Yahoo! that his email account records had been subpoenaed. He skipped town, and when federal agents knocked on the door in February, it was clear to Brewster the gig was up.

Fed up with his ex-roommate by then, Brewster says he had no problem telling the investigators what he knew. They left, and he figured that was it. But they returned the next day. "They threw me on the floor in my Walking Dead pajamas and slippers," he says.

Brewster was charged with being a co-conspirator in the identity fraud scheme. He pleaded guilty in June 2016 and was sentenced to seven months in prison and ordered to pay $14,159 in restitution. He says he prayed a lot in prison, and God has answered. He has a new life. He says he doesn't hang out in the streets anymore and doesn't even smoke marijuana.

"In the Bible it says the truth can set you free," he says. "That's why I'm free."

Today, Brewster is a 31-year-old minister-in-training at Shekinah Glory Church in Granite City. After he got out of prison in October 2016, he reconnected with a woman he had known since they were teens and got married. They had a son — DeMarcus Brewster, Jr. — in December. Everything is going well, and he wants nothing to do with Duncan anymore.

"I'm trying to get as far away from him as possible," he says.

That is difficult considering they were one person, at least on paper, for so long. "DeMarcus Brewster" got a driver's license from the DMV and set up bank accounts. He rented apartments in Hillsboro and Indianapolis. He worked for Uber and LongHorn Steakhouse and maybe a CarMax, judging by one of the letters that have continued to arrive. He even played Lacey several years ago in a college performance of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.

Brewster says Duncan's version of the story is a lie. He claims he never stole his stuff (though he concedes that someone did). And while he admits that he did let his former friend use his name and information, he says Duncan took it much further than he ever realized, signing him up for schools and applying for jobs he knew nothing about. A year before either of them went to Hillsboro, Duncan even enrolled at an online school called National American University and collected a $5,505 refund check after paying the tuition. Investigators say he didn't give any of that money to Brewster.

"Malachi — he lies," Brewster says. "He lies."

Beyond that, he says, Duncan wasn't just using the funds to go to college. He was feeding a gambling habit, he alleges, accompanying his biological mom to casinos around St. Louis.

Duncan acknowledges he did gamble, though he says it wasn't nearly as bad as authorities or his old roommate have alleged. Investigators found he spent $147,622 at three St. Louis-area casinos between 2012 and 2015, although Duncan correctly points out that figure includes money he won and pumped back into the machines. He also says he let other people play on his cards, although he does not say who.

Regardless, he says he made bad decisions. He knows his deal with Brewster was never going to work in the long run. You cannot be someone else forever. But Duncan says he was not thinking long-term.

"I've never done anything thinking I'm going to get away with it," he says. "I'm going to do what I can to get from one day to the next."

Brewster had already served his time and was out of prison by the time law enforcement finally arrested Duncan in March 2017 in Memphis, where he was taking English classes under another name and working in a computer lab.

He pleaded guilty in July. The judge in his federal case took pity on him and arranged his sentence to run simultaneously to any punishment he might receive in a trio of pending state court cases in Missouri and Illinois. But he will still serve nearly four years in prison and owe more money than he can imagine ever paying back.

His attorney, Jason Korner, says it wasn't as if Duncan was just using the financial aid for an easy payday. After all, he went to class and got involved on campus. He was using the money to be a college student. His crime is that he lied about who he was in order to obtain it. "I'm no psychologist, but you could see he wanted an escape from his life," Korner says. "He's not knocking over banks. He's somebody who wants to be someone else."

If anyone understands that impulse, it's Duncan's oldest biological sister, Elizabeth Williams. Now 50, she was the only one of her twelve siblings then alive who survived the fire that consumed their home.

In many ways, their childhoods were quite different. "I was the product of twelve children, and then all of a sudden I was alone," she explains. "That's where we were divided."

Lately, though, they've been growing closer. Williams has been writing to Duncan every week while he's locked up. He pens his responses in careful, handwritten pages. In other jails, he has typically landed in protective custody as a result of being attacked by other inmates or on suicide watch. But he says he has worked to avoid that in Ste. Genevieve in order to keep his mail privileges.

His sister understands that Duncan is upset with their mother. She says she had a lot of anger and acted out on it for years, but she eventually got her GED, went to college and got a master's. She is now a social worker and has been writing a book about what she's experienced.

She has never really made peace with what happened, she says, but she realized she had to move forward. She's not sure Duncan is there yet.

"In his world, he probably feels like my mom is the reason for everything in his life," she says. "It's easy to blame her for our whole, entire life, but at some point as an adult, you have to take accountability for what you've done."

That does not mean it is easy, or that she feels any less of a connection to him. "We've both been through hell and high water, and we're still standing."

And Duncan, too, is writing a book. Unlike his sister's, though, his is fiction, a novel called Shogun Ninjas. It is about a superhero from a broken home who learns he has three brothers. The boys end up in foster care and briefly turn to a life of crime. The twist comes when they repent and learn to use their powers for good.

"They all get the chance to do better with their lives," he says.

Like all his favorite stories, it is a fantasy.