His son had been in jail a week before Greg Herter learned about the killing.

A family friend had come across a news story about the case, recognized the last name and forwarded it along.

A mix of horror and anger hit Greg Herter as he read the news story. "It could have been prevented and should have been prevented," he says.

The father, who lives in Virginia and spends most of his days on the road as a long-haul trucker, says after his son left home they had limited contact. Until a recent visit at the St. Louis jail, he had not seen him in person since 2010. But they exchanged flurries of emails and sometimes calls. Often, Herter was angry and asking for money, says his father, who suspected he was on drugs.

On April 16, two weeks prior to the killing, the father dialed the number to the Behavioral Health Response crisis hotline in St. Louis.

He has had countless bizarre exchanges with his son over the years, but their most recent conversations had frightened him.

"It was getting dark," he says. "It was getting darker."

The younger Herter was convinced Jesus wanted him to start punishing people. Greg Herter says he tried to reason with his son. He talked about the mathematical improbability that of all the billions of people in the world, he alone was the chosen one. He tried explaining Jesus would never want him to hurt anyone. Nothing seemed to get through.

Greg Herter hoped Behavioral Health, a private nonprofit that provides services in St. Louis, would send counselors to speak with his son and have him involuntarily committed. The organization declined to confirm the call when contacted by the RFT, citing privacy laws, but phone records provided by Greg Herter show his call on April 16 lasted 55 minutes.

He says the woman he spoke to asked if his son was suicidal or homicidal.

"I said, 'No — he's just homicidal.' That's exactly what I said," Greg Herter says.

That alone should have set off a red alert, says the father. Instead, he claims he was told the best they could do was ask police for a welfare check — which sounded like a disaster in the making. The elder Herter told the counselor that his son had grown paranoid, recently cutting open his own ear in search of a chip implanted by the CIA.

"Seth was not in a state of mind to see uniformed officers at his door," Greg Herter says.

After the helpline phone call, Greg Herter was stymied. The news story he read about the killing was the realization of a nightmare.

Parts of it still don't make sense to him. Police said his son had claimed to be on his way to Mexico, but he says the young man barely knew how to drive and wonders how he managed to make it beyond St. Louis County. There was no way, he insists, his son was actually trying to flee across the border with no money or resources.

"As soon as I read the headline, I knew it was absolutely false," he says.

Greg Herter suspects police wanted to make his son appear cogent. He has been trying to investigate what he can and pull together relevant legal documents, hoping to show otherwise. He has been able to get his son's bank records, including a handwritten withdrawal for the last $92 in his account. The transaction was posted about 8:30 a.m. on May 4, the day of the arrest. Maybe it will turn out to be significant, maybe not.

Greg Herter wants the courts to see what he sees: a seriously ill young man, who could have been prevented from doing something terrible and who would not be a threat again if his mental illness was addressed.

"He took someone's life," the father says, "but his life is still worth saving."

In the justice center awaiting trial for murder, Seth Herter has a mostly nocturnal routine. He says he wakes about 2:30 p.m., giving him an hour before his unit has a two-hour recreation period. After that, he returns to his cell, lays down on his bunk and eventually drifts off about 5 a.m.

"I don't talk to anyone," he says.

He would like a judge to find that mental illness rendered him not responsible for his actions. He thinks, with a little help, he could live a productive life.

"I'm not a dangerous person," he says. "This was just a big mistake. I've never hurt anyone else. I don't want to hurt anyone."

Herter's criminal record includes at least seven arrests in Texas and Missouri. The charges vary, but there are patterns in the police reports: erratic behavior, suspected and sometimes confirmed drug abuse and chaotic clashes when cornered by arresting officers. He was arrested three times during one three-month stretch in Austin.

In a case from March 2013, a man who met Herter on a dating app and let him move in told Austin cops he had become afraid of his young lover's unpredictable fits of rage. When officers arrived, Herter was at first calm but suddenly tried to bolt over the side of a second-story balcony. He was shocked twice with a Taser before officers dragged him to a patrol car, according to the incident report.

"This always happens with older guys," Herter reportedly shouted as he was hauled away. "They give you a place to stay, and when you don't give them enough dick, they get mad."

None of Herter's charges were major. Austin police charged him with resisting arrest, evading arrest and criminal mischief. His lone assault case is from a 2015 incident in the St. Louis suburb of Breckenridge Hills. Police say he smashed out the window of a methadone clinic and then kicked the police officer who tried to restrain him in a patrol car, according to court records.

Dr. Meredith Throop says it is extremely rare for someone with Herter's diagnosis to become violent. In such cases, it is usually only one of many contributing factors and often not the driving one.

Throop is a psychiatrist and the medical director of Places for People, a St. Louis-based mental-health provider. She has not treated Herter but says the symptoms he described to the RFT are right in line with those of psychotic disorders. Even so, the vast majority of people dealing with even severe psychosis never hurt anyone.

In Herter's case, he says he also had PTSD, which Throop says can make people hyper-vigilant. And he had a deep interest in weapons. He says he always thought an ability to use weapons was practical knowledge, so he set about training himself. On the day of the killing, Herter says, he believed he was under attack. He thought the people in the walls and furniture planned to kill him. Throop says those kind of delusions feel entirely real to the people experiencing them.

Herter claims the final trigger was McCarthy himself. He claims his former lover tried to sexually assault him, and that he defended himself with the sword. Whether McCarthy did in fact attack him is probably unknowable. It is not uncommon for people in the midst of psychosis to misunderstand the actions of others.

"When you misperceive someone's actions, and you see it as a threat, you're willing to do about anything, because you're protecting yourself," Throop says.

Combine delusions of schizoaffective disorder with hyper vigilance, a long history with weapons and the perception of a life-or-death threat, and you begin to get a broader picture, Throop says. "It sounds almost like this was a perfect storm."

Herter hopes he will be free again one day, but he is pessimistic. He says when he needed help in the past, it was nowhere to be found: "Everyone abandoned me. My family walked away. My friends walked away." By the end, he lived alone, pinning mass times to his bulletin board and wearing a hairshirt around his apartment.

The legal battle will not be easy. Herter will be evaluated to see if he is competent to help with his defense, and also to try to determine his mental state at the time of the crime. To be considered not guilty for reasons of mental disease or defect, he would have to prove he did not know what he was doing was wrong, which will depend on a psychiatric examination and expert testimony, says Susan McGraugh, director of Saint Louis University's legal clinic. It is very difficult to earn acquittal.

"Even if every psychiatrist who sees him says he had a mental illness, a severe mental illness, that's not enough to win at trial," McGraugh says.

Prosecutors will likely point out every step he took after the killing — blocking the maintenance man's entry, leaving town — and suggest they show attempts to conceal the crime or get away, which would mean he knew the killing was wrong. Even if he never actually planned to go to Mexico, they will still be able to show he stole McCarthy's SUV and drove off. "That's how everyone loses," says McGraugh, who has defended mentally ill clients throughout her career.

Herter, though, says he had no plan when he got in the SUV: "I was still freaking out." He holds out some hope that a judge will understand, but not much. "I think about, I'm going to lose my life over this. One person has already lost their life over this. Do two people have to lose their lives?"

He thinks about this as he lays in his cell, and he thinks about Tim. He still calls him Tim, because that's the name he knew. "I loved him."

And yet, he wonders if he ever really knew him. He thought "Tim" was in his 30s. He is fairly certain Tim worked as a truck driver for a small St. Charles-based company called M Aubuchon Hauling. He would call sometimes from the job, and Herter could hear background noise as if he was in the cab of a truck. But the rest is hazy. They rarely went out anywhere or hung out with anyone other than Krechel. "I think he was friends with me because he expected sex," Herter posits.

The only thing Tim ever really told him about his background was a story about being adopted by a family of gospel-singing evangelists who took him into their band and family only to cut ties later in life when they discovered he was gay and had been contacting men online.

Herter accepted the story at the time, but as he tells it now, he realizes how far-fetched it seems.

"I'm a gullible person," he says. "I believe what I'm told so much, a voice told me to kill someone and I did it."

Christopher McCarthy is a puzzle.

No obituary appeared in the local papers after his death, and a search of public records reveals little. A medical examiner's spokeswoman confirms someone has claimed his body from the morgue, but she declines to say who. Contacted by the RFT, M Aubuchon Hauling makes it clear they want absolutely nothing to do with the story. "Please do not contact us," says the emailed reply to a reporter's calls and messages. "Where [sic] not interested."

Even so, a picture slowly emerges. A man who let an unemployed McCarthy live with him several years ago says he was funny and entertaining. He had worked on and off in construction but had trouble keeping jobs. And, yes, he performed with a family of gospel singers.

"He was funny," says the man, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. "Obviously, I liked him. Otherwise, I wouldn't have tried to help him."

The only problem with McCarthy, says the man, was that he lied compulsively. It was never clear why. He was not a thief, and he did not seem to be trying to make himself look better. "He has nothing to cover up. He was not into drugs. He would lie about the stupidest things." The man suspects some of his stories stemmed from his role in the gospel group, whose members would not have accepted his sexuality. "They're crazy. So maybe that's why he was making up names."

He believes McCarthy's real first name is Rich, which he says he confirmed by looking at his driver's license.

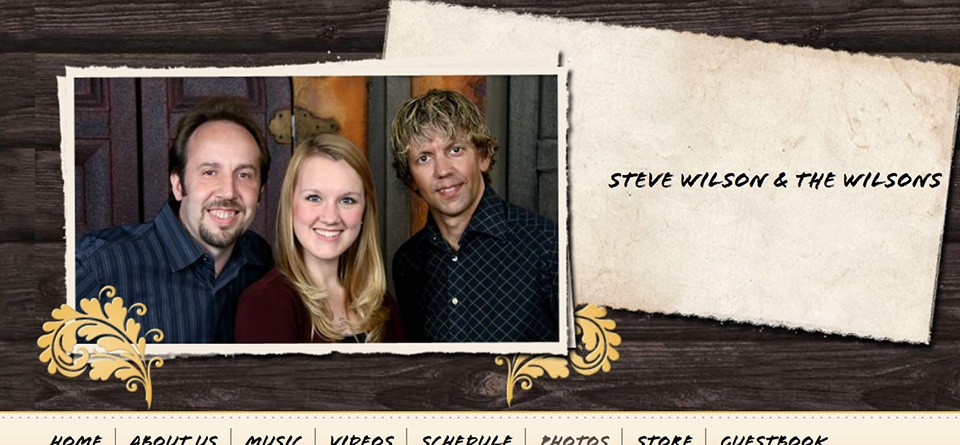

Lisa Tegart, 41, also knew McCarthy as Rich — Rich Wilson, then Rich McCarthy and later Rich McCarthy Wilson. He was part of a Ballwin-based gospel group called the Wilsons. The story she heard as a kid was that the Wilson family had spotted him walking along the road and took him in.

"He could sing," she says. "He played bass, so they stuck with him."

Her family had its own Southern gospel band, the Prices, out of Rolla. The two groups were close, and Tegart's mother was later hired by the Wilsons as a singer. She remembers touring together on weekends, often not returning home until 3 or 4 a.m. "Many nights we slept on a bus. There were nights we slept at their house."

McCarthy was in his twenties then and seemed even younger. "He was always talking to people, laughing, telling jokes at the table."

The Wilson parents eventually retired, but the band regrouped under their son as Steve Wilson and the Wilsons, a trio that featured McCarthy. He appears on multiple album covers, and his photo remains on the homepage of the group's website.

Tegart says she had lost touch with McCarthy in recent years. She heard he had been fired from the band but never got the full story of why — something to do with his "lifestyle" and playing music in bars, which wouldn't be allowed. (The Wilsons did not respond to phone messages, an email and a letter from the RFT.)

"I was under the impression that it was a pretty rough fallout with the family," Tegart says.

Only later, through a friend whose brother had worked with McCarthy, did she hear about his murder. Even then, it was difficult to find information, in part because the papers said his name was Christopher and she had always known him as Rich. She does not know what to make of all the names or how he came to be killed in the grimy bathroom of a delusional twentysomething.

"I really had been curious about where his life had gone for this to happen," she says. "The Rich I knew was the least likely to be killed by someone with a samurai sword."

Whatever he called himself, Tegart says McCarthy was her friend. She wishes she knew if he had a funeral service or where he was buried.

"He had a rough, complicated life," she concludes. "He really did, but he was so fun. I always said he was a big kid."