For the past five years, Cynthia Wren, 66, has applied to get her ten-year-old granddaughter, Ariel Gibson, into St. Louis' student desegregation program.

The Voluntary Interdistrict Choice Corporation, or VICC, oversees the student transfer program. It is a race-based transfer that allows black city children to attend county schools, even as white students in the county can attend city magnet ones.

Ariel is black and lives in the Shaw neighborhood of St. Louis city. Part of her application includes ranking her interest in much more highly rated suburban districts. If she's chosen, it could be a ticket to a top-tier public school district: Brentwood, Kirkwood, Clayton.

But she hasn't gotten in. So the ten-year old attends Tower Grove Christian Academy. In lieu of sending her granddaughter to an elementary school run by the St. Louis Public Schools, or SLPS, Wren pays Ariel's private school tuition. A former teacher's assistant and current substitute for St. Louis County Special School District, Wren says that paying Ariel's tuition is a hardship for her family.

"It's not always easy," she says. "But we do what we have to do."

Wren plans to continue applying to VICC for her granddaughter in the years to come. But it's a lottery situation, and with a 17 percent acceptance rate, the odds are against her.

"I just don't understand the situation," Wren says. "[Ariel's] being skipped over and it breaks my heart to know she hasn't gotten in."

Ariel isn't alone. In 1999, VICC reached its peak enrollment of 14,626 students. Since then, though, the program has been on steady decline. Last school year, 4,392 students were enrolled.

It's not a case of lessening demand. A total of 2,488 black students living in the city applied to VICC for the 2017-2018 school year. Just 413 were accepted. (Of the 148 white students from the county who applied to attend St. Louis magnet schools through VICC, 85 were accepted.)

And the clock is ticking for Wren and her granddaughter. This month marks the official beginning of the end for the desegregation program, beginning the five-year extension that provides one final reprieve before the education leaders running VICC plan to shut it down entirely.

VICC oversees the longest-running race-based student transfer program in the nation, and even as it's brought a dose of color to many affluent county districts, it's also been a real boon to thousands of lucky city kids. State Representative Bruce Franks (D-St. Louis), who graduated from Lindbergh High School in 2002, is just one prominent alumnus.

Yet if you ask the people in charge of the program — the superintendents of the twelve schools that make up VICC's governing board — what comes next, and what they'll be doing to increase diversity in districts that would be largely monolithic absent the transfer students, they'll acknowledge they don't know just yet.

"We want to roll into this new five-year extension," says Eric Knost, Rockwood superintendent and VICC chairman for the 2017-2018 school year. "Once things start to settle a little bit, we will start talking about what's beyond the five-year extension."

He acknowledges, "We really haven't even scratched the surface yet on what's to come."

Since 1981, more than 70,000 black students from St. Louis city have attended schools in St. Louis County through the VICC program. Under its auspices, white students from the county have also been attending magnet schools in the city since 1982, albeit in much smaller numbers (9,000).

Those students have added much-needed diversity to some county districts. In 1999, the year of VICC's peak enrollment, participating county districts notched an average of 20 percent black students. Had VICC not existed, the projected black enrollment would have averaged a mere 4 percent.

Nearly two decades later, not much has changed, demographically. In 2017, black enrollment within participating districts averaged around 15 percent. Without VICC it would've been just under 7 percent.

But as the years have gone by, some of VICC's original participants have pulled out. Hazelwood, which was steadily growing more diverse even without transfer students, left in 1988. Ladue and Ritenour both exited in 1999, Pattonville in 2005 and Lindbergh in 2011. (Students in the program were allowed to graduate from the districts they'd been placed in, making the districts' withdrawal a gradual one.)

According to VICC, the districts left the program after finding other ways to enable diversity in their schools. Ladue, for example, consolidated its ten neighborhood elementary schools to four in the 1970s. At that same time, Ladue also redrew its school boundaries. In doing so, the district, which is made up of nine municipalities (Creve Coeur, Crystal Lake Park, Frontenac, Huntleigh Village, Ladue, Olivette, Richmond Heights, Town and Country and Westwood) plus some parts of unincorporated St. Louis County, created more racial diversity in its schools.

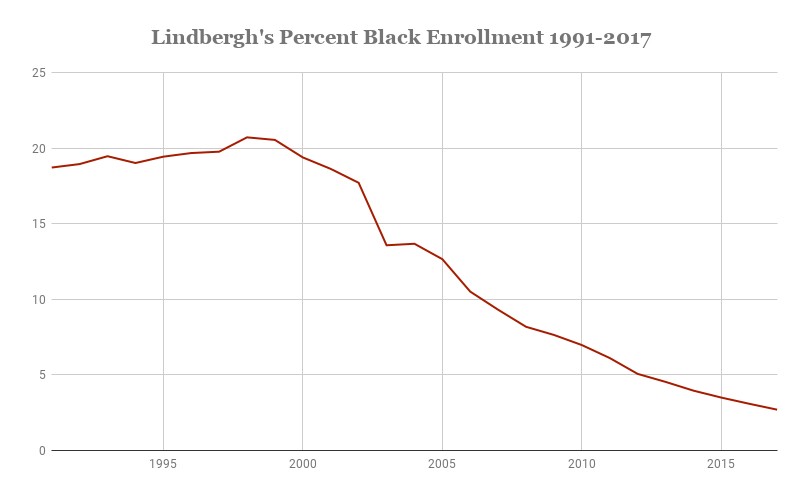

Lindbergh, though, hasn't quite done that. The district saw black enrollment as high as 20.56 percent in 1999 thanks to its participation in VICC. By the time it pulled out, that had dropped to 6.11 percent. Lindbergh's last VICC student graduated in 2017, and at that point, its black enrollment had sunk to just 2.69 percent — around ten times smaller than it was in 1999.

In the coming years, absent some sort of replacement transfer program, what's happening at Lindbergh could happen to districts across the county.

VICC's board approved that final five-year extension in November 2016. It's set to run from the school year that just began through 2023-2024 and will accept around 1,000 students into the twelve participating school districts during these five years. Priority for acceptance into VICC during its final extension will be given to siblings of students already in the program.

It's a long goodbye, by any measure. If a kindergartner is chosen for the program during its last year, 2023, he or she wouldn't be on track to graduate until 2036 — walking an increasingly lonely road as other minority students graduate and move on.

From its inception, VICC's model was built on continual phase-out. The program was set up in 1999 to dwindle at a rate of 5 percent over a twenty-year period. And that's exactly the outline its remaining districts are following.

VICC leaders say that their long-held plan to phase out the program dovetails nicely with the growing ambitions of the St. Louis Public Schools. After all, VICC takes black students to county schools who would have otherwise been zoned to attend city schools.

"Clearly, county schools benefit [from VICC] by creating a more real and diverse student environment," Knost says. "At the same time, we have got to keep the interest of the SLPS."

In 2012, the St. Louis district regained provisional accreditation after five years of operating as non accredited. In 2017, the district became fully accredited.

"We are trying to be competitive as we can for families to look at us as a real option," SLPS superintendent Kelvin Adams says.

But while Adams says he believes the desegregation program has fulfilled its purpose, he agrees the ending of this iteration of VICC may not mean the end of transfer programs between the city and county school districts.

"I'm not saying it can't continue in some way, shape or form in the future," Adams says.

Maalik Shakoor, 22, graduated from Clayton High School in 2014. He was bussed from his neighborhood of Baden in north St. Louis for the twelve years he was in VICC: first to Bierbaum Elementary School in south county, then to Clayton for middle and high school.

Shakoor graduated from Webster University in May with a degree in film production. He's spent the summer as a teacher at the Freedom School in St. Louis.

Though Shakoor wishes he could have gotten a strong education in his own neighborhood, he sees the value in VICC.

"If [black children in the city] can't get a good, quality education where they're at, then the next best solution is to bus them out," he says. "Until the city schools can be up to par with the county schools, I see no other option."