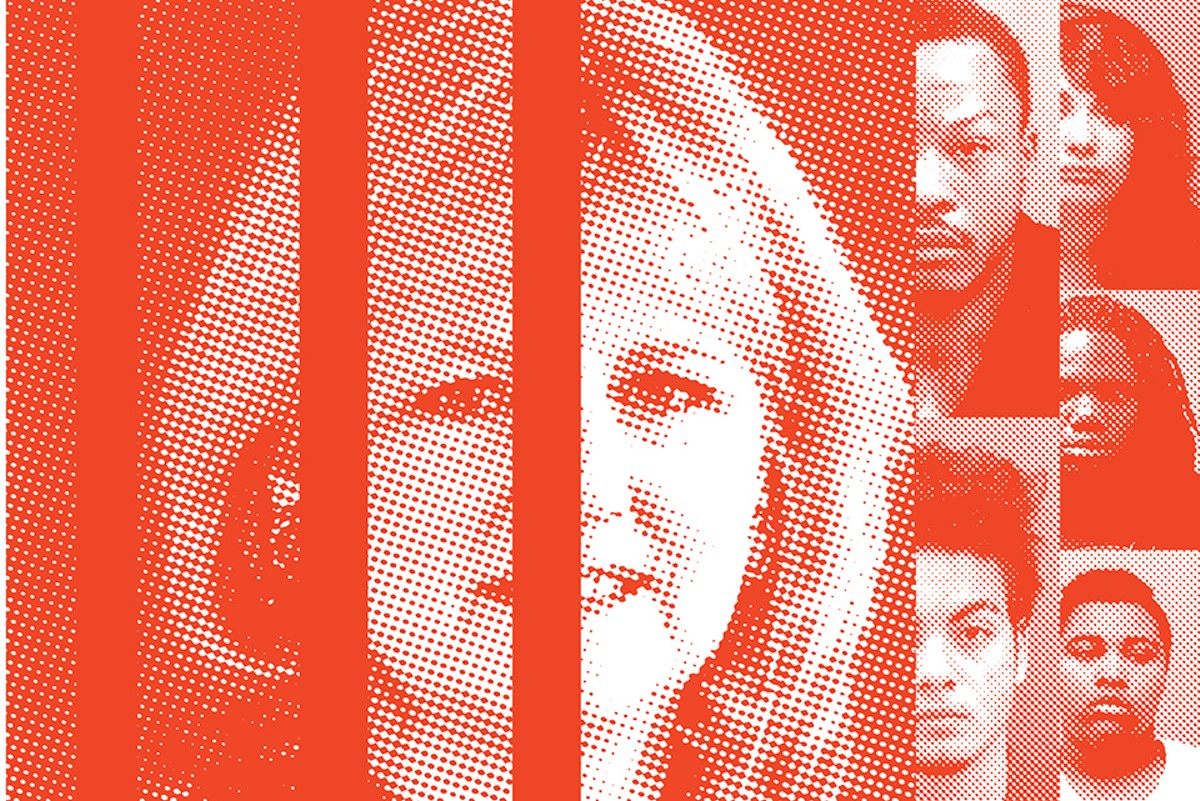

Nothing about Deborah Pierce's background suggested she was a crook.

Then again, that's how it works. White-collar thieves are able to steal a lot of money, because they seem trustworthy enough to oversee lots of money.

Pierce, now 63, was hired in 2007 as the director of the Confucius Institute at Webster University after nearly 30 years as a foreign languages professor at Mississippi College, her alma mater. It wasn't just that she was respected in her field; students and colleagues loved her for her generosity and nurturing ways outside of class. In letters written on her behalf and collected in a federal court file, they credit her with keeping them afloat with homemade dinners, tuition money and motherly support when they needed it most.

"My first week at Webster I met Debbie Pierce," writes one former student, who came to study in St. Louis after surviving the Rwandan genocide. "That was the luckiest day of my life."

And so it came as a shock to many when a federal indictment revealed that the beloved academic, a daughter of Southern Baptist missionaries, had been embezzling money from her employer for more than two years.

The institute was a partnership, jointly funded by the university and Chinese government to promote research and exchange of cultures. Pierce had set up a secret bank account in September 2013 to divert payments from the Chinese Ministry of Education and used them to pay her bills and those of her family.

She was caught in 2016 when an internal audit by Webster uncovered problems with the institute's books. That led to an investigation by the FBI and U.S. Postal Inspection Service. Federal authorities would eventually tally the amount of missing money at $375,000.

The fallout was swift. Pierce resigned even before her arrest in November 2016. Her husband, who also worked for the institute but was not implicated in the fraud, resigned as well. She pleaded guilty to one count of transporting goods across state lines the following September and was scheduled for sentencing in March 2018.

All of that led to the inevitable question: What would be a just punishment?

Every day across the country, versions of that question are taken up by judges, jurors, prosecutors and defense attorneys in an endless stream of cases. They are debated by criminal justice reformers, victims' advocates, law enforcement and the elected officials tasked with protecting or reshaping key components of our system, such as mandatory minimums or whether felons should be allowed to vote. This August, they are sure to be front and center when former St. Louis County Executive Steve Stenger gets sentenced in his pay-to-play case. Stenger's case has more than a few things in common with Pierce's, from his status as a first-time offender to his guilty plea. Stenger and Pierce are even represented by the same law firm. (Perhaps you've heard of Rosenblum Schwartz & Fry, home to prominent defense attorney Scott Rosenblum?)

Often, the outcomes hinge on almost random variables: the jurisdiction where the case is being handled, the attorneys or judges involved, even shifting attitudes toward punishment. Penalties are generally more severe in federal court, but not always.

Mary Fox, who leads the St. Louis office of the state public defender, says we have grown comfortable as a society with long prison sentences, nearly oblivious to the extreme act that is locking a human in a cage.

"For 95 percent of the people that come through the criminal justice system, it's a spur-of-the-moment bad decision," she says. "We respond to that moment with a very lengthy sentence."

Often, those bad decisions are made by men so young their brains are still developing, Fox adds. And yet those moments can freeze them in place with long-running prison terms. Curious one day, Fox researched the origins of jailing people who break society's rules. At first, it began as a way to hold people until violent punishments, such as death, could be administered. But it soon became the punishment itself, a progressive alternative to lynchings or beatings. The English are often credited with creating the modern prison system in the 1700s and 1800s. It has evolved some in the past two or three centuries, but Fox finds it odd that it has not been supplanted with something better.

"We really haven't advanced much from those days," she says. "We still don't know how to deal with people we're mad at."

Missouri is one of the few states in the country that has seen its prison population continue to grow in recent years. The Sentencing Project — a research and advocacy organization working against mass incarceration — looked at state and federal prison populations across the nation, comparing each state's number of people locked up in 2016 to its highest-ever totals. All but eight states had seen at least minor decreases from their peak years.

But Missouri's prison population was larger than ever. In 2016, it had increased by a little more than five percent over the previous five years. Legislation has been introduced in Missouri that would reduce the prison population, says Nicole Porter of the Sentencing Project, such as eliminating sentences of life without parole. But other than some minor reforms with limited impact, the bills have so far hit political walls in the legislature.

That has kept the state from moving resources from prisons to prevention, Porter says.

"In order for Missouri to pass significant changes that would lower the number of people in prison and open up resources to crime prevention, there would have to be a significant shift," she says.

Even so, St. Charles County Prosecuting Attorney Tim Lohmar, who is the president of the Missouri Association of Prosecuting Attorneys, says he has seen a change over time in the way prosecutors approach sentencing, especially when it comes to drug cases or low-level offenses.

"Fifteen years ago, I think a lot of prosecutors and the judiciary wouldn't think twice about sentencing a person without a prior offense to prison," he says.

Assistant prosecutors in St. Charles County will still start with a recommendation of prison for the most serious felonies, he says, which include violence and crimes against children. One of the first priorities is to keep the public safe from dangerous people. People who continue to re-offend and have shown themselves unlikely to change also merit prison sentences, in his eyes.

After that, though, Lohmar says the general policy in St. Charles is to seek other alternatives for people convicted of mid-level felonies or lower.

"We're looking to keep people out of jail," he says.

Still, he balks at some of the bills proposed by reformers. Lohmar says the best way to reduce the prison population is not by limiting sentences on the front end, but by allowing the state parole system to continue to determine which inmates have proven themselves worthy of release.

"You're putting a significant amount of responsibility on the inmates" to demonstrate good behavior, he says.

In making any recommendation on sentencing, he says he considers unique aspects of the case, such as the age of the defendant, the need for closure for victims and what combination of conditions — possibly including prison — could prevent defendants from repeating their crimes.

In the end, however, prosecutors are only one voice in the process.