He was the most notorious bootlegger in the rural Midwest, and with the help of some gangster peers and an arsenal of Tommy guns he broke the back of the Ku Klux Klan at a time when that organization was a force to be reckoned with in southern Illinois. A household name in this part of the country in his day, he inspired terror and love in equal measures, and nearly a century after his death, his restless soul still calls out for our attention.

Some facts still resist untangling. He was either born in Russia in 1880 (by his own account), or in 1881 (so writes Wikipedia), or in what's now Lithuania in 1882 (his sister's version) or in 1883 (according to his gravestone). His name at birth was Schachna Itzik Birger, but everybody called him Charlie. His hideout, the Shady Rest, was situated on Route 13 somewhere between Marion, Illinois, and Harrisburg, Illinois, but there's no agreement among historians and aficionados as to the exact location of the site.

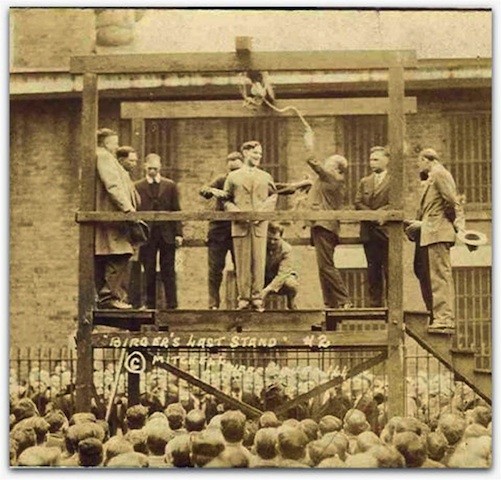

What's not in dispute is that he was hanged outside the Franklin County Jail in Benton, Illinois, on Friday, April 13, 1928, for the murder of Joe Adams, the mayor of West City, Illinois, and that he lies buried in Chesed Shel Emeth, a Jewish cemetery on Olive Boulevard in University City, Missouri.

Charlie Birger's defunct state notwithstanding, on a cold, dry February night close to 90 years after the last public hanging in the state of Illinois, a cheerful cohort is gathered at the former jail-turned-museum where Birger spent the last year of his life to see if the old bootlegger has anything to say for himself.

Benton is a city of about 7,000 people, located roughly an hour-and-a-half drive east of St. Louis, just south of Rend Lake, right off Interstate 57. Its town square, dominated by the Franklin County courthouse where Birger was tried, is also home to an antique row, and a few blocks away is a vintage auto museum. In the early 1960s, George Harrison's sister Louise lived here, and when the Beatle spent two weeks in Benton in 1963 — already famous in the U.K. but unknown here — Harrison played with a local band at a nearby VFW and gave an interview on WFRX radio in which he played a 45 of "She Loves You." (WFRX had earlier, thanks to Louise's persistence, become the first station to play a Beatles record on American airwaves.)

At the outset I'd intended to write a straightforward piece about Birger, but I'd made a trip to Benton the week before to take some pictures, and museum volunteer Bill Owens mentioned that a group of ghost hunters were coming the following Saturday. I asked if I might come and talk to them.

The Franklin County Jail Museum's reputation for being haunted sprang partly from a series of electronic voice phenomena (or EVP, in the parlance of that subculture) that a ghost hunter recorded at the jail in 2013. Also, an infrared photo taken from the exterior of the building at that time revealed what looked to some like an image of Charlie Birger himself peering out the window of his cell at the street below. (His supposed face, it must be noted, materialized in a window of the sheriff's living quarters at the front of the building, an area that would presumably have been off limits to him in life. It's understandable, though, that his ghost might prefer that window to the one adjacent to his cell, which offers a view of a full-scale replica of his gallows, built after the jail was decommissioned in 1990.)

At one point in a ten-minute video the ghost hunter posted to YouTube in 2013, a disembodied voice whispers "Should I stand by the screen?" while the camera is pointed at the screened window overlooking the gallows. At various points in the video other such breathy phrases as "Help me," "Tell me a story" and "I can't help it" can be heard, although in fairness they sound to some ears like currents of air blowing over the windscreen of a camera microphone. The video has been viewed more than 20,000 times.

I've been in the building several times in daylight and found the vibe unnerving; at night, of course, it's considerably eerier. As for my own attitude toward such things: A movie producer once asked me, apropos of a script I'd collaborated on about a haunted restaurant, whether or not I believed in ghosts. "No," I said, "but I'm scared of 'em." The movie never got made, but I stand by my answer.

Tonight's ghost hunters call themselves 618 Paranormal, an affable group of sincere, youngish men and women who cheerfully answer my questions as they busy themselves setting up video cameras and audio recording equipment in the cellblocks, the old jail kitchen and the long-unused basement, which features a door to an underground tunnel that, according to legend, once led to the county courthouse a few blocks away and then further on into downtown. It was through this tunnel that Charlie would have been led from his cell to the courthouse to stand trial.

Bill Owens opens the door and I peer in to see mops and empty bleach jugs. I take a few flash photos of the deeper part of the tunnel, but all I capture are some old soda bottles. Owens points out that the basement was where new prisoners were brought for intake and also for interrogation; for that reason, tonight's group has placed a remote camera down here. Gloomy and dusty as it is now, in Birger's day it certainly saw some grim business. All kinds of ghosts might be down here, or none at all.

This raises the question of why Charlie Birger's phantom in particular should haunt this building, or why anyone might care one way or the other. He hasn't been forgotten, precisely, though his legend has dimmed somewhat over the decades. Older residents of the region still remember stories told by parents and grandparents about the biggest, baddest bootlegger agrarian Illinois ever saw, and there may even remain a handful of elderly witnesses to the hanging, which was so well-attended that spectators climbed nearby trees to get a better view of the grisly affair.

Lurid pencil illustrations with descriptive typewritten captions of some of the Birger gang's doings, posted around the walls of the two cellblocks, may help to explain his continuing relevance. They were made years after the events they depict by one Harvey Dungey, a former member of the gang. He was a talented but untrained artist, and the drawings have a wonderful naïve quality, vivid but stiff, as though Grandma Moses had decided to document armed robberies, bombings and wanton murder. He intended to travel around the region showing the drawings and telling the story of the gang, but the lure of perfidy was stronger than that of art; in 1958, Dungey attempted to rob a tavern and was shot to death by a night watchman, leaving behind this remarkable trove of firsthand visual accounts.

In early childhood, Charlie Birger, along with his parents, had followed an older brother from Russia to St. Louis (where for a time young Charlie was a Post-Dispatch newsboy) and later to southern Illinois. This was coal country, then as now, and as Jews and immigrants, the Birgers represented everything a certain element feared and hated about the changing nature of rural America. Formerly Protestant towns like Herrin, Benton and Marion found themselves home to immigrants from the Appalachians, from southern and eastern Europe as well as Ireland and Wales, all come to work in the coal mines. These new citizens' dietary and religious customs did not always jibe with the local norms. Nor, significantly, did the taste of some of these communities for alcohol.

In the years before 1919, when the Volstead Act banned the production and sale of "intoxicating liquors" across the nation, Charlie was already running a small coal country vice empire. Following stints as a miner, a soldier and a cowboy, he had returned to Illinois, married a woman from East St. Louis (he had three wives in all, and two daughters) and settled down in Harrisburg. There he opened up a saloon called the Near Bar, which also served as a casino and brothel. But it was Prohibition that really made Charlie, turning him from a small-time country operator into a full-fledged gangster.

In the modern imagination Prohibition tends to figure as an urban phenomenon, with rough speakeasies in Chicago and Manhattan sophisticates drinking bathtub gin in suites at the Algonquin. Rural Illinois, though, like most of America, was never going to go without its booze. Charlie and his quickly expanding gang joined forces with the notorious Shelton brothers of neighboring Williamson County to distribute alcohol throughout coal country.

For a few years things went swimmingly for the Birger and Shelton gangs. Charlie was a remarkably charismatic man, good-looking and charming, and he was seen as a hero by many, particularly in Harrisburg, where he made sure the crime rate stayed close to zero. Apart from the vice operation and the occasional shooting, the Birger gang committed the bulk of its crimes elsewhere.

But by late 1925 things had started going south for Charlie, and when they did, the end came at an astonishing rate of speed.

By then, the nativist locals had had it, and membership in the newly reactivated Ku Klux Klan was surging. Klansmen were going door to door to confiscate liquor and arrest — or abduct, since they had no legal standing to do so — anyone caught with it. Officeholders seen as soft on bootleggers were replaced by Klan members.

Law enforcement in Saline County, home to Harrisburg, was no longer as friendly to Charlie as it had been, so he crossed the line into Williamson County to open up a combination speakeasy, barbecue joint, gas station and hideout: the Shady Rest. There was live music, dancing, gambling and, out back, cockfights and dogfights.

Troubles with the Klan worsened and the bootleggers were faced with the prospect of losing large sums of money where it operated. Though Birger's relations with the Sheltons had deteriorated considerably, the two gangs managed to join forces one last time in April 1926 at a township election in Herrin, Illinois, a notorious hotbed of Klan activity.

Rumor on both sides had it that the day would see trouble, and when Catholic voters were turned away from the polls by a prominent local Klansman named John Smith, fistfights broke out. Later in the day Smith was shot at on the street by an unknown assailant and his garage was sprayed with slugs from Tommy guns. The bootleggers had come to defend their customers — and their own economic interests.

Bullets flew from passing cars and hotel windows, and the National Guard was called in. At the Herrin Masonic Lodge, Birger's men pulled up and exited their vehicles, confronting and disarming the Klansman who had replaced Smith as poll watcher. A nearby Klansman shot Charlie's man, another Birger ally shot the Klansman, and all hell broke loose. By day's end three of Birger's men and three prominent Klansmen lay dead.

The body count may have been even, but the dead Klan members were higher-ups, and it had become clear that the Tommy-gun-toting gangsters had the advantage in armaments. Herrin and its surrounding countryside were traumatized, and the KKK's local organization dazed and demoralized. John Smith even left town for good. The consensus was that the gangsters had prevailed.

The Klan's defeat notwithstanding, relations between the Birger and Shelton gangs were worse than ever, and in the following months that tension erupted into all-out war. As the bodies started piling up, Charlie took to wearing a bullet-proof vest (it's in his cell at the museum) and started driving an armored car. The Sheltons had one of their own, and they needed it.

The Shady Rest has the distinction of being the site of the first aerial bombing attack in the United States. The war between gangs had intensified by November 1926, with a bomb thrown at the compound's barbecue stand. Shortly thereafter the home of Joe Adams — Stutz automobile dealer, mayor of West City and staunch ally of the Sheltons — was machine-gunned, though no one was injured.

In retaliation that same day, an airplane flew over the Shady Rest and dropped three packages of dynamite. The historic moment was a bust; only one package detonated, and with no injuries. (Though, according to Gary DeNeal's biography, A Knight of Another Sort: Prohibition Days and Charlie Birger, the explosion killed a bulldog and a bald eagle.)

About a month later Joe Adams answered his door one Sunday afternoon to two men, one of whom handed him a letter, purportedly from the Sheltons. While the mayor read the note, one of the men shot him dead. That murder would become the crux of Charlie's downfall.

On display in one of the front rooms of the Franklin County Jail Museum is the wicker coroner's basket in which Joe Adams' body was placed the day he died. It was reported that, as Charlie Birger was being led to the scaffold, he spat into a similar basket intended to carry his own body back to St. Louis for burial.

Charlie was still a free man when, a month after the Adams murder in January 1927, a series of explosions hit the Shady Rest. It burned to the ground with four people inside, presumably associates of Charlie's, though positive identifications were never made.

Another Birger associate, a crooked Illinois motorcycle cop named Lory Price who patrolled the patch of Route 13 that passed by the Shady Rest, became concerned that Charlie had turned against him. Price then made an ill-advised attempt to collect a $2,500 reward offered for information regarding a recent bank robbery in the area, and Charlie got wind of it.

On January 17, Price and his wife Ethel vanished. Ethel Price had been a young, pretty schoolteacher on maternity leave, and her disappearance caused a local uproar. The activities of the gangs had grown increasingly violent, and for a well-known and well-liked member of the community to fall victim to the bloodletting was a shock.

Lory's corpse was found on February 5, but his wife's body was not found until June 13. She had been shot and dumped into a mine shaft shortly before her husband's execution.

When the shooter confessed that June, he explicitly named Charlie Birger as the man who ordered the hit. By that time Charlie was in custody, and public opinion, which had long cut him considerable slack for his charm and the good will he'd built up since he'd opened the Near Bar all those years past, had turned resolutely against him.

He had been arrested shortly after the Adams murder and released on bond. He was arrested again a day before one of the triggermen in the Lory killing confessed and fingered him. He was kept separately from the other prisoners, in a larger cell where he was allowed certain luxuries, such as a gramophone and a collection of records (the gramophone is in the cell today.)

In July 1927 he stood trial for the murder of Joe Adams alongside the two men he'd ordered to commit the crime. The other two received prison sentences, but Charlie was sentenced to hang. He spent the next nine months in the Benton jailhouse, pending appeals and waiting.

When the day came, it was noted by many in the crowd that Charlie was smiling as he climbed the steps to the scaffold. This may have been bravado, or it may have been the effect of the morphine shot administered shortly before leaving his cell. Accompanied by a rabbi, Charlie had a black hood placed over his head (he had requested it, rather than a white one, so as not to be taken for a Klansman) and the executioner prepared the noose. Known as "the sympathetic hangman," as a boy Phil Hanna had been witness to a bungled hanging that resulted in a prisoner's agonizing, fifteen-minute death by strangulation, and he had taken up the trade determined to prevent such atrocities.

"It's a beautiful world" were Charlie Birger's last words.

I don't know if Charlie haunts the jail, or somebody else's ghost, or anything at all. But it's a scary, lonely place at night. If there is an afterlife, maybe this is an appropriate place for him to remain, stuck alone in the same miserable spot he spent the last year of his existence.

Two weeks after Paranormal 618's investigation, I call Seth Clark. Yes, he, tells me, they did get "a few last words" out of Charlie.

The actual gallows, along with the thick rope used to hang Charlie, was found in a barn in 2013 and purchased by the museum. It lies unassembled, with the rope coiled on the stacked beams, in the old women's cellblock on the second floor, its cell walls long ago painted pink, paint now curling away in strips from the bars and walls. Next to the noose Seth and Mike placed several cameras and what they call a spirit box. The notion behind this device is that by rapidly scanning radio waves, certain sounds will pop up through the white noise as intelligible words.

Late in the night of the investigation, several members of the team gathered in the women's cellblock and were startled by the squawking of the spirit box, which began making intelligible sounds. The resulting scene was captured on video, which can be watched on the group's YouTube channel.

When the group starts discussing who should remain up there alone, the box says quite plainly "MIRANDA." One of the group present at that moment is a young woman named Miranda Stewart.

"Charlie, do you want me to stay?" she asks. The box replies in the affirmative. When she asks if someone else can stay with her, the box says "THEY HAVE TO GO."

But the voices stop, and after a few minutes it's decided that Mike and Seth will stay and Miranda will go. Over her shoulder as she leaves the cellblock, Miranda calls out "Bye, Charlie."

The box replies: "RECONSIDER."

——-

Scott Phillips is a novelist and screenwriter. His novel The Ice Harvest was made into a movie directed by Harold Ramis and starring John Cusack, Billy Bob Thornton and Connie Nielsen. He is also the editor of St. Louis Noir, an anthology due out in August from Akashic Books.

Author's Note: Southern Illinois poet and publisher Gary DeNeal’s superb biography of Charlie Birger, A Knight of Another Sort: Prohibition Days and Charlie Birger, is still in print and well worth your time. Most of the biographical facts above come from that book, though some of it I gleaned from visits to Franklin County Jail Museum and other relevant southern Illinois locales. For more on Birger, please see www.heritech.com/soil/birger/birger.htm and www.carolyar.com/Illinois/Govern/Birger.htm