One morning, a federal prosecutor named John Davis was driving to his job at the U.S. Attorney's Office in St. Louis when he looked in the rearview mirror of his Toyota Yaris and spotted a BMW flying up behind him on Interstate 64.

Davis eyed the luxury car as it grew larger and larger in the mirror. When it blazed past him, the driver was a blur, but he immediately noticed the name on the vanity license plate — TANCO.

"One of these days, I'm going to get that guy," Davis said aloud.

For years, the career prosecutor had heard about Todd Beckman, the founder of a chain of tanning salons called TanCo. The perpetually bronzed CEO was a local success story, turning a tanning bed in the back of his father's beauty parlor into a small empire that extended across more than a dozen states. He opened not just tanning salons but massage parlors and gyms. In the coming years, he would debut yet another concept — a line of hormone and supplement centers, offering aging men the promise of recapturing their youthful vigor.

It was a lifestyle Beckman not only sold but embodied. Then in his mid-40s, he was a notorious playboy with blond highlights in his hair and a smile worthy of a toothpaste ad. He had a reputation as a hard-partying daredevil with a fondness for beautiful women, gaudy automobiles and anything that could go fast. He was even for a time a professional powerboat racer on the Formula One circuit, blitzing across waterways from Creve Coeur to the Florida Keys.

All that was fine, but it was Beckman's rumored side business, importing crates of marijuana, that interested Davis.

A month older than Beckman, the prosecutor had spent his federal career assigned to the Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Force, which focuses on large-scale narcotics conspiracies. Part of the job was talking to defendants who hoped to trade information on the bad deeds of others in exchange for shorter prison sentences. In those conversations, Beckman's name had come up often enough to make Davis suspect the tanning mogul was up to something more than peddling a year-round glow to strip-mall customers.

Agents from the Drug Enforcement Administration had also taken an interest in the flashy CEO, according to an agency official. So far, they did not have anything to present to prosecutors. Frankly, Beckman was a small fish compared to the major traffickers moving heroin, cocaine and mass quantities of marijuana through the metro area. And yet a supposedly legitimate businessman brazenly flouting the law had a way of annoying those responsible for enforcing it.

Davis watched the BMW and its TANCO plates speed out of sight. That was that.

But then, about four years later, in December 2016, the prosecutor was groggily watching the 4 a.m. news when the story of a vicious kidnapping caught his attention. A young Maplewood man had been abducted from his home, beaten and tortured for three days until his family paid a $27,000 ransom.

The names of four suspects — a pair of twenty-something brothers named Blake and Caleb Laubinger, 24-year-old Zachary Smith and 55-year-old Kerry Roades — meant nothing to Davis. But mention of the fifth made him sit up in bed.

"Did I just hear 'Todd Beckman'?"

Todd Beckman's marijuana arrived every month in shipments from California. An eighteen-wheeler would back up to the loading dock of his corporate headquarters at 11 Champion Drive in Fenton and offload crates of what appeared to be industrial toolboxes.

It was a good cover. The building, which included offices and a large warehouse, was the nerve center of Beckman's wide-ranging interests. Over the years, more than two dozen corporations have been registered there under his watch. Some fizzled, but others, including MassageLuXe and LifeXist gyms, had grown into multi-state franchises. The warehouse teemed with motorcycles, sports cars, racing go-karts or whatever else happened to grab Beckman's attention.

When a St. Louis Post-Dispatch reporter visited in 2010 for a profile of the successful entrepreneur, she noted walls covered with photos of him racing during his Formula One days, along with a "human-sized trophy" planted near his desk.

"You've got to be motivated," Beckman told her. "That's why I have all those pictures here. They're not just because I like to see myself. It's because it reminds me of winning."

With everything going on, no one was going to notice a couple nondescript crates arriving every four weeks.

It was Kerry Roades' job to handle the incoming cargo. A capable mechanic and generally handy when it came to building or fixing things, he had helped take care of the literal nuts and bolts of Beckman's big ideas for two decades. Once the crates were in the warehouse, Roades cracked them open and retrieved the true payload — between 50 and 80 pounds of marijuana in airtight packaging.

From there, the weed went to Blake Laubinger, a dull-eyed young drug dealer who started as an investor in one of Beckman's gyms and became an awestruck protégé. Laubinger stashed the pot at his house in the small town of Pacific, Missouri, parceling it out to a network of low-level dealers and then collecting the proceeds from their sales. He and Beckman split profits of about $800 per pound and sent the rest back to their supplier in California. On an 80-pound shipment, they could each clear $32,000, maybe more if the market was good.

The operation hummed along month after month until October 2016, when Laubinger returned home to find his house had been burglarized. The 24-year-old searched desperately, but it was just as he feared — his safe with $15,000 and 24 pounds of marijuana was gone.

In a panic, he called both Beckman and his older brother, 26-year-old Caleb Laubinger, and told them what happened. He even called Pacific police and reported the burglary, although he wisely omitted the bit about the missing marijuana and drug money.

Both were problems. Not only had Blake Laubinger fronted his network of dealers — putting up the weed on the promise of being paid after they sold it — but Beckman had fronted him. Forget about profits; he was now in debt tens of thousands of dollars to the tanning mogul, and he worried about the consequences.

"I mean, it wasn't a good situation," Blake later told prosecutors. "There was a lot of money lost, and I had no way of paying it."

In the short term, he says, his brother loaned him $75,000 to buy time. (Caleb Laubinger claims it was only $3,000.) But the only real solution was to find the burglar and get their money back.

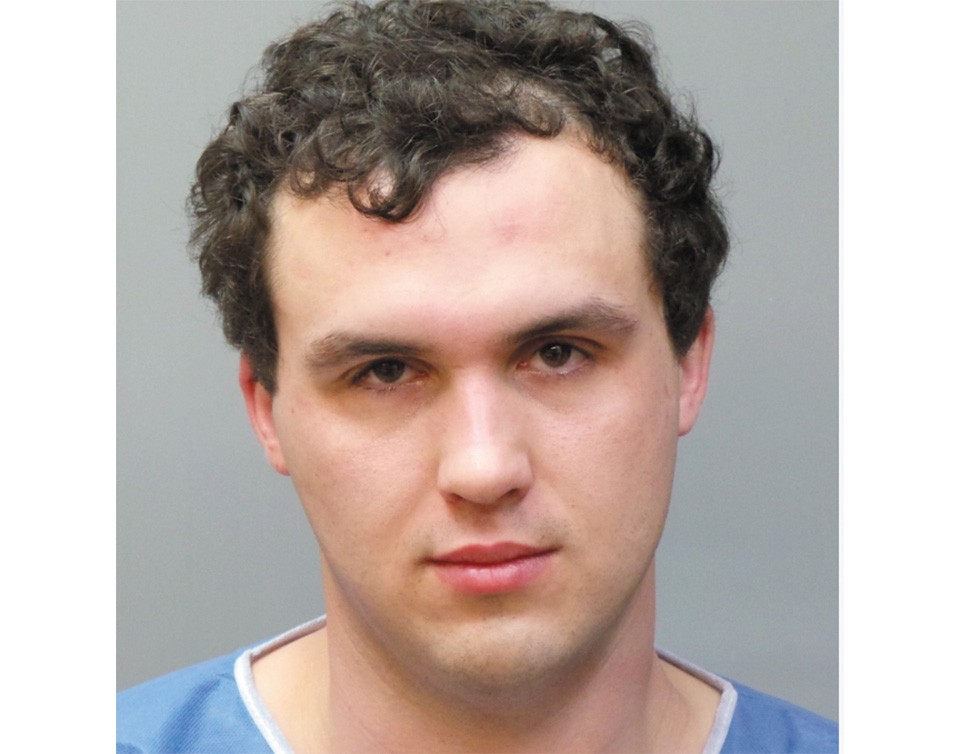

Luckily for Blake, he knew exactly who had ripped him off. A fellow drug dealer, Ellis Athanas III, knew where Blake kept the marijuana and had easy access to the house, because the two 24-year-olds had been literal partners in crime ever since meeting in 2010 at St. Louis Community College. Both were student drug dealers at the time and decided to team up.

Athanas had long, light brown hair that hung past his shoulders, contributing to his surfer-bro vibe. He had met Beckman just once (when the middle-aged entrepreneur complained of an aching back, Athanas suggested they go to hot yoga together), but he knew when the shipments were incoming. After all, he was one of the people who had helped sell them.

Athanas had been peddling marijuana since he was about sixteen years old but recently had grown more interested in daring drug ripoffs. "Seizing dealers' assets," is the way he described it.

Blake Laubinger had teamed up with him on a few such escapades. Athanas would arrange to meet another seller in an out-of-the way location, snatch the drugs and speed off in his car. Blake, parked just out of sight, would wait until his partner passed and then pull his truck across the road, cutting off any pursuers.

Now, he discovered, he was the one whose assets had been seized. And his former accomplice was on the run.

The Laubinger brothers spent more than three weeks desperately hunting Athanas. They told mutual friends to watch for him, and soon tips began to trickle in. They missed him in Springfield after he was supposedly spotted hanging around Missouri State University. They almost had him another time at a Steak 'n Shake in Sunset Hills, but he bolted through a back door, jumped in his car and escaped during a wild, wrong-way chase on I-44. Athanas was turning out to be a ghost.

Adding to the pressure was Blake's relationship with Beckman. The young dealer's attorney, Scott Rosenblum, would later describe it as nearly paternalistic. The Laubingers' own father had been physically and emotionally abusive, Rosenblum told a judge, and Blake was easily impressed by Beckman's money, cars, beautiful women and "sparkling tan." The younger man talked about his buddy "Todd" so much so that his mother began to wonder about what she assumed was another twenty-something. She was alarmed when she discovered her son's new friend was a middle-aged CEO.

On social media, Blake hyped his new lifestyle and connections. Alongside a photo of his ride next to Beckman's souped-up sports car, he wrote, "Me and todd on the way to the race track had to snap a pic lol."

But Rosenblum contends there was always an "element of fear" in the relationship. And when Athanas stole his money and drugs, Beckman was adamant that Blake "get" him, authorities say.

The Laubingers finally caught a break on November 21, 2016, when they learned Athanas was staying at a house in Maplewood. That evening, they slipped inside and waited in the dark. It was a modest place — two bedrooms, set off a one-block street south of Manchester Road — and the brothers searched for any sign of the stolen bounty. They knew it was a long shot. Blake had heard Athanas bought not one, but two luxury cars after the burglary. He was making them look stupid. And the money was still gone.

Their target finally returned home after an evening out, and Blake punched him hard in the face. Six feet tall and 200 pounds, Blake had a size advantage of three inches and about 30 pounds. But Athanas was wily. A fitness fanatic, he occasionally posted shirtless photos of his ripped physique on social media and filmed himself doing acrobatic flips. The two rivals traded blows in the cramped kitchen.

The fight ended when Caleb, bigger and stronger than them both, rushed in from behind. He clamped his arm around Athanas' windpipe and squeezed until the smaller man passed out. Blake bound his adversary's wrists and ankles with plastic zip ties.

When Athanas awoke, Blake grilled him about the drugs and money, but he was too late — Athanas had already sold all the weed and spent the cash.

Blake called Beckman to tell him what happened, and then the brothers carried their captive outside to a truck. It was dark outside, and things were getting complicated. They still had no money and no drugs, and now they had a live hostage who knew plenty about them.

The Laubingers crept out of the neighborhood and onto the highway. Blake drove while Caleb sat in the back with Athanas. It is a 30-minute trip from Maplewood to Pacific, and Athanas was frightened. Part of the reason he was so hard to find after the burglary was because he had fled to Florida, where his mother lives. Now that he was back, he wondered if he was going to be killed.

As the truck sped down the highway, Athanas made one last, frantic attempt to escape. He flung himself into the front seat and kicked furiously at Blake. The truck spun out before Caleb was able to grab Athanas, punching him and dragging him back into the rear seat.

Once they arrived at Blake's house in Pacific, the brothers pulled into the garage and carried Athanas down to the basement. They laid a plastic tarp across the floor — for the "blood stains," they said — and tied their hostage by his wrists to a pole.

Within the hour, Beckman and Kerry Roades arrived. The tanning mogul glared at Athanas.

"You fucked up," he said.

It was like a movie — like the four had watched a bad movie about drug dealers or kidnappers and decided this was the way to handle a thieving double-crosser.

The plastic tarp was one thing. Then Beckman pulled electric hair clippers out of his backpack. Athanas had spent years growing his hair, proudly measuring the length at 26 inches. If there was one thing Beckman understood instinctively, it was the psychological power of your looks. The former hairstylist had, after all, become a rich man by playing to his customers' vanity. Now he intended to turn it against his captive as a form of mental torture.

The clippers buzzed as Beckman shaved Athanas' head down to the scalp. When he was done, he collected the hair and said he planned to send it to his marijuana supplier in California to prove they had caught the thief.

Athanas later testified the men took turns beating him. Blake had a Taser, and they shocked him over and over as they threatened his life. Roades suggested they shoot him, chop him into pieces and shrink wrap him for shipment back to the supplier in California, according to Athanas. Beckman alternately pistol whipped him and jammed the barrel of the gun against his head, pulling the trigger with a sickening click as the pistol's hammer slammed forward into an empty chamber.

"I was convinced I was going to die," Athanas later testified.

Blake's French bulldog, Louie, had befriended Athanas during previous visits. At one point, all the screaming and beating freaked out Louie so much the protective pup nipped Beckman's face.

Finally, sometime after midnight, Beckman and Roades went home, leaving the Laubinger brothers to keep watch. Athanas was a mess. He had two black eyes and cuts across the top of his head. His face was puffy and swollen, and the cartilage in one shoulder was torn. The zip ties used to bind his wrists and ankles had cut off the blood flow, causing his hands and feet to turn darker and darker purple as they went numb. He begged the brothers to let him go or at least loosen the restraints, but it was no use.

In the morning, Beckman returned. He had been shopping at Lowe's, and he held up a roll of shrink wrap and a heat gun. If Athanas did not come up with some cash, Beckman warned, they really would kill him and ship him to California.

It was to be a long and violent day. By now, the four kidnappers knew Athanas no longer had their money, so they settled on a new plan — they would call his parents. They dialed his father in St. Louis first, then his mother in Florida. During the calls, they put Athanas on the phone, demanding he ask for money. They beat him so his parents could hear him suffer and warned if they did not pay, their son would be dead by Thanksgiving — two days away.

The calls — and beatings — continued throughout the morning as the kidnappers increased the pressure. The worried parents started gathering cash, but it was difficult. They were working-class people with no piles of money lying around. Athanas' father rehabbed houses, and his mom had her nursing license. Slowing the process, the mother had to drive from Florida and would not arrive until the next day.

Blake was getting worried about the crime scene unfolding in his home. The house was surrounded on all sides by neighbors, including ones just across a small backyard from the walkout basement where he and his friends had been torturing a man for nearly 24 hours. Anyone was liable to show up.

In fact, one of Blake's buddies, 24-year-old Zachary Smith, did just that. Smith, who had gone on one of the unsuccessful Springfield search missions, tromped down to the basement where Athanas dangled from his wrists, his head shaved and covered in bruises. There would later be some debate about whether Smith took a turn with the Taser or just watched and left. Regardless, they needed a more secluded location.

Beckman suggested moving the operation to some rural land owned by the Laubinger family, but Blake balked at that idea. Instead, they settled on a wooded property Beckman had on the edge of Fenton. He and Roades left to make preparations.

Blake and Caleb waited until dark, then loaded Athanas into a rented blue pickup and headed out. Athanas watched out the window as they turned onto I-44 again, this time headed east. As they neared Six Flags, they draped a blanket over his head so he could not see.

Riding blindly, he felt the truck pull over. The door opened, someone else got in and he heard a familiar voice.

"Now we're going to take you to where you're going to die," Beckman said, according to Athanas.

The tanned CEO reached back and clocked him in the head with a pistol. Blake put the truck in gear, and the four of them turned back onto the road.

Todd Beckman's land in Fenton was on the top of a hill overlooking Bud Weil Memorial Park.

He had been renovating a two-story house there until a suspicious explosion wrecked the place in 2006. According to law-enforcement records of the investigation, St. Louis County detectives found a gas line had been left wide open, filling the garage with combustible fumes until a space heater, stuffed with paper and hot wired to an electric timer, kicked on. The blast cracked the walls, blew out windows and flung the garage door 50 feet from the house. Neighbors more than 400 feet away felt their homes shake and called 911. Investigators noted it could have been worse — the five-gallon containers of fuel staged around the heater somehow did not ignite.

Beckman had left for Cancun just before the incident. Detectives later arrested one of his boyhood friends, a caretaker for the property, on an arson charge (they found a charred scrap of envelope addressed to the man among the shreds of paper near the heater). But county prosecutors later dropped the case, and a lawsuit Beckman filed against his insurer, which had denied his homeowner's claim, was settled out of court.

By the time the kidnappers arrived on November 22, 2016, it was an eerie sight. A large fish pond sat in a clearing just beyond the end of the drive. Where the house once stood was barren ground. The trio dragged Athanas out of the truck. His hands and feet were still cinched together by zip ties, and they had added a set of handcuffs. He hopped along as they pulled him by his shoulders toward an industrial shipping container at the edge of the property.

Kerry Roades, the jack of all trades, had anchored steel cables to the inside of the container. The men laid their hostage on a blanket and fastened his arms and legs to the cables. They continued to beat him as they worked. Athanas was a mass of bruises on top of bruises by then.

"I was terrified," he later testified. "It was the scariest thing that's ever happened to me in my life. I really thought I was going to die."

Once they were done, the kidnappers shut the heavy steel doors to the container and left Athanas lying in the cold of the November night. He was wearing khakis and a long-sleeve shirt. The cables didn't have enough slack to permit him to stand, so he just lay there in the dark, listening to rain beat against the shipping container. A small hole in the roof was his only light.

Blake Laubinger returned alone the next day to the shipping container. He was apparently feeling some remorse, or at least pity for his former partner.

"It was cold," he said later. "It was cold and wet, and I was checking on him."

He brought Athanas a double cheeseburger from McDonald's. It was almost over, he told him; Athanas' parents had agreed to pay a ransom.

Athanas spent the rest of the day in the container. It was true his parents had scraped together as much cash as they could — $27,000 — but Beckman also wanted the BMW and Mercedes that Athanas had bought with his ill-gotten gains. That proved to be a little trickier, and it led to one of the strangest episodes of the three days.

The plan, as Beckman devised it, was to go with Athanas' father, Ellis Athanas Jr., to get the vehicle titles from the dealerships, hoping the matching names would be enough cover for the ruse.

The plan did not work. The father and son may have had similar names, but the car dealers quickly recognized something was off. They remembered the son. How could they not? He was young, looked like a surfer and paid $23,000 cash for a Mercedes. Same name or not, this blue-collar guy in his late 50s was not their customer.

Beckman and Athanas Jr. reconvened at Joey B's to work out the details. What they needed was a power-of-attorney form, Beckman decided. He called Blake to pick up the form at TanCo's corporate office and bring it to the restaurant.

When Blake arrived, he found the two middle-aged men sitting together, drinking beers. For anyone else observing the scene, it was unremarkable. Beckman claimed he was trying to work out a solution, "dad to dad." But to Blake, the sight of the kidnapper chatting with Athanas' father as the young man lay bloody on the floor of a shipping container was surreal.

"Weirdest thing I had ever seen," he said later.

After a few more minutes of negotiation, the father left, and Beckman and Blake finished their beers. They later met Athanas Jr. in a parking lot where he handed over $27,000. After three brutal days, the kidnappers finally had at least some of their money back. With any luck, they would soon have the cars, too.

Beckman and Blake drove back to TanCo's corporate headquarters on Champion Drive. It was just the two of them now, the mentor and his protégé. They made their way through what was essentially a tribute to Beckman's success, walking under the giant logos of his top brands to the office where he liked to keep all those reminders of winning.

They counted and sorted the ransom money into stacks of bills. A few more hours, and they would be done with this caper. Now, they just needed to go pick up Athanas.

As it grew dark on the third day, Athanas heard the door to the shipping container swing open and looked up to see Beckman and Blake.

It was his lucky day, Beckman said: His father had come through with the money. The tanning mogul slapped Athanas across the head with a handgun, kicked him a couple of times and then jammed the gun barrel to his hostage's head.

"I should still kill you," he said, according to Athanas. "I should just shoot you right now." Instead, he pulled out a power-of-attorney form and ordered him to sign it. Beckman was still thinking about those cars.

Once the paperwork was done, he and Blake hauled Athanas out of the container and put him in the back of a van. Bleary from three days of beatings, near-constant terror and an estimated 50 or more jolts from a Taser, Athanas was still lucid enough to notice the TanCo logos on the van.

The three rode south for about 25 minutes before pulling into Gravois Bluffs Plaza in Fenton. Over the years, Beckman had made these kinds of sprawling shopping centers his home, gauging the flow of shoppers and comparing price-per-square-foot rents to see if they would be right for a chain massage parlor, gym or maybe a supplement shop.

They pulled the van around behind a Smoothie King. Blake handed Athanas a cellphone and told him his dad was nearby and expecting his call. Before they put him out of the van, Beckman gave him one last warning: Go to the police and they would kill him and his family. Then they were gone.

Athanas dialed his dad and walked free for the first time in three days, scanning the horizon of asphalt parking lots and uniformly beige-colored block buildings. He was bald, battered and shaken from the beatings. When he finally located his father and walked up to his car window, the older man barely recognized him.

Athanas Jr. took his son to the hospital. There, doctors surveyed the effects of three days of torture and promptly called the police.

At first, Maplewood detectives did not know what to make of his story. It was so crazy as to be almost unbelievable. Athanas refused to give them names or addresses, but the specifics of the violence he endured were starkly specific, and he clearly had the wounds to match.

"His head was swollen like a grapefruit," Detective David Brown recalled.

It took another week before Athanas agreed to identify his attackers. Assured that detectives weren't interested in going after him for selling weed, he and his attorney arrived at Maplewood Police headquarters the week after Thanksgiving 2016 and laid out a stunning story of violence and torture carried out by one of the region's most recognizable businessmen.

The Maplewood detectives quickly recognized they would need more manpower and called a contact on a DEA task force. Local police hadn't been too familiar with Beckman, but as soon as they mentioned his name, the feds perked up. Soon, agents from the DEA and FBI, along with local cops, had joined the case.

"They brought a small army," Maplewood Police Lt. John LeClerc says.

The blended team of investigators worked quickly, methodically matching Athanas' wild story to a growing number of verified facts. Eight days after the traumatized 24-year-old was dumped behind a Smoothie King, they were ready to make arrests.

Early on the morning of December 1, 2016, an FBI special agent and a St. Louis city police officer sat in an unmarked Dodge Charger outside a house in Fenton. Beckman's ex-wife lived there with their two young kids, and he stayed over some nights.

Shortly after sunrise, the special agent and the cop watched as Beckman walked out and got in a white Subaru. They carefully trailed him to a convenience store and then a condo he used as a bachelor pad.

As he walked toward the front door, they popped out of the Charger, shouting "Police! Police!"

Beckman, seeming a little dazed, continued to fumble with a keypad on the door until the two-man crew tackled him onto the front yard, pinning him face down in the grass. Two more task force members swooped in and secured his wrists with handcuffs.

Similar scenes played out across the St. Louis metro as teams of law-enforcement agents picked off the kidnappers one by one. By mid-morning, only Roades was unaccounted for.

The suspects were driven to the DEA's local headquarters, where Maplewood's LeClerc and Brown were preparing for interrogation.

Neither man had handled a kidnapping case before, but they knew their way around an interview room.

"As detectives, if there are multiple [suspects] involved, you think about who is the weakest, who is going to talk to you," LeClerc says.

"Who's going to fold first," Brown adds.

They soon discovered they were not dealing with the toughest of criminals. Blake, the aspiring big shot, started to cry. Caleb folded, too.

The detectives had figured they would get little from Beckman. A big-time corporate executive like him was almost guaranteed to call in an attorney, a good one, after about three seconds.

Instead, to their delight, he talked for three hours.

"He just couldn't help himself," Brown recalls. "We just let him talk. He kept digging himself deeper and deeper in the hole."

They led with a good cop/good cop routine. Beckman was pissed about having his face mashed in the ground that morning, but these two detectives seemed OK.

"Interesting start to the day, huh?" LeClerc offered.

Before they knew it, Beckman was rattling on about his busy schedule, chatting about a female employee on her way to his place that morning and the go-kart racing expert from Los Angeles he was flying in that afternoon to coach his kids. He asked whether the police had secured the two money clips he had been carrying when arrested. He also had two cellphones — make that three cellphones.

"That's my girlfriend phone," he added slyly.

"Oh, ho, man," laughed Brown. "I love it."

As Beckman continued to loosen up, they began to ask him about various players in the case. Blake was a "great kid," Beckman said, but he knew little about his brother, Caleb.

"Well, let me throw another name at you," Brown said, "Ellis Athanas."

Beckman shook his head.

"No dealings with him?" Brown asked. "Nothing like that?"

"No."

But a few minutes later, Beckman's memory improved: "What's his name again?"

It was soon coming back to him. Athanas was the kid who burglarized Blake's house, he recalled. Yes, in fact, Beckman had tried to help negotiate a solution, agreeing to take the title to Athanas' car, sell it and give Blake the money to settle the debt. He even remembered meeting for beers with Athanas' father to make it happen, he said.

In his telling, Beckman was simply a peacemaker trying to help out his young friend, who'd had his house burglarized.

"He called me freakin' crying on the telephone that he'd lost everything," Beckman told the detectives.

Brown and LeClerc listened, silently cataloging the admissions that corroborated what they already knew. After about 40 minutes, they began to turn up the heat.

"You're not being straight up with me on Ellis," Brown told him.

He and LeClerc began to lay out the details of the kidnapping, torture and ransom payments. They questioned him about the pole in Blake's basement, the shipping container. If Beckman was under the impression the detectives had been blindly lobbing questions, they were now deliberately showing him that they'd done their homework.

"Todd, how do I know all this?" Brown asked about an hour in.

Investigators had already collected video from Lowe's of Beckman buying shrink wrap and a heat gun on the second day of the kidnapping. They had run the GPS on Athanas' phone showing him in Blake's basement, they told him, and they would soon do the same to Beckman's phones. His smartest move would be to start telling the truth, they said.

Beckman then admitted he had seen Athanas in the basement. He told the detective he had advised Blake to make a "citizen's arrest" after the burglary. Athanas was a "shithead" who "would have got it sooner or later," Beckman added, but he insisted he never hurt the 24-year-old. "I'm the nicest freaking guy you'll ever meet."

Yet even as Beckman tried to minimize his role, he admitted to key parts of the narrative: He was at the scene of the crime, he had negotiated ransom payments over beers with the hostage's dad and he'd advised Blake to snatch — "citizen arrest" — Athanas.

Incredibly, Beckman was not done cooperating even after the interview ended. He signed consent forms for investigators to search his condo and Subaru, leading them to discover the handgun he used to pistol whip Athanas. He even accompanied police to his office in Fenton. His attorney, Travis Noble, met them there on Champion Drive.

"I think in Todd's mind, it wasn't a kidnapping," Noble later tells the RFT. "It was, 'We grabbed a guy who stole from us and we want our stuff back.'"

Beckman certainly conducted himself as a guy with nothing to hide, even as federal agents piled up crucial evidence. He led them to the safe in his office where he had stored $5,000 of the ransom money. And he suggested where they might find the keys to a certain TanCo van that seemed of particular interest. While they searched, he picked up a glass, poured himself a belt of vodka and gulped it down. Noble, left with little else to defend his client, later argued that the investigators had let his client get drunk, asking a judge to throw out any statements Beckman made to the Maplewood detectives. But it was already too late. Davis, the federal prosecutor, successfully pointed out that Beckman gave his long-winded interview before he did any drinking. The statements were fair game, the judge ruled.

As an added bonus that day at Beckman's office, investigators discovered Kerry Roades milling around outside and took him into custody as well. LeClerc and Brown tried to interview him, too, but he was clear: He wanted an attorney.

Everyone pleaded guilty. They quibbled about a few of the details in a list of facts composed for each plea hearing — Beckman said he couldn't remember pistol whipping or dry-firing the gun against Athanas' head, Roades claimed he wasn't part of the torture — but they had been caught. Even Zachary Smith, the 24-year-old who dropped by Blake's during the kidnapping, admitted he failed to report a serious crime and was ordered to serve fifteen months behind bars. As part of the plea deals with the four main defendants, Davis agreed to recommend sentences of no more than twenty years in federal prison.

Caleb Laubinger, who had been pulled into the incident by his younger brother, fared the best. U.S District Judge Audrey Fleissig gave him five years and ten months. Blake's attorney, Rosenblum, made a compelling case during his sentencing that his client had been manipulated by his mentor after a childhood of abuse.

Fleissig described the actions of the four as among "the worst conduct I've had to deal with in my time as a judge," but she agreed that the kidnapping and horrific beatings seemed far beyond Blake's nature. She sentenced him to six and a half years.

"I would truly like to say sorry for what I did," Blake told the judge, fighting back tears. "I wish I could take it back."

Roades also apologized, but Fleissig was less merciful. Davis had long considered the mechanic the savviest of the four — the "alpha criminal" in a crew of amateurs. He notes that Roades was careful to position himself behind Athanas, out of his sightline, during the attacks. Unlike the others, he never talked to investigators.

"Kerry pretty much stonewalled it until the end," Detective Brown says.

Athanas testified that it was Roades who suggested they chop him up and shrink wrap the pieces to ship to California. And yet friends and neighbors wrote passionate letters to Fleissig, begging her to have mercy on him. An Arnold cop who lived in the same subdivision as Roades and Beckman claimed that his two neighbors had little do with each other outside of their business dealings.

"I can't stress enough that Kerry is truly one of the good people," the veteran officer, Jason Valentine, wrote. "I have seen him work hard every day of the week providing for his family, and at the end of a long day, it was not unusual to look out my window and see him mowing my lawn."

Fleissig sentenced Roades to ten and a half years in prison. Only Beckman received the full twenty years recommended by prosecutors.

His daughter, the oldest of his three kids, gave a speech that Davis would later describe as "gut-wrenching," attesting to the kindness of her father and the way he could motivate a roomful of people. He had been arrested on the day of her engagement party and was still locked up when she got married. Beckman listened quietly. His tan had faded after more than a year in jail, and his dark hair was going gray at the temples but was somehow still perfectly styled.

Fleissig noted that while he clearly cared for his own children, he showed no mercy to the parents of Athanas.

"I have never seen a case like this," the judge said. "I have seen cases where some horrible things took place, but short of somebody shooting or killing somebody, I have never seen a case in this court where a defendant has elected to abduct, detain, threaten, terrorize a person and then turn around and threaten and terrorize that person's parents."

Beckman didn't even need the money, Fleissig added. He had "millions in assets," according to court filings, yet he tormented his victim for three straight days.

"It is one of the most violent and callous series of facts I have ever run into as a judge," Fleissig said.

Left unanswered was why.

"If you figure that out, let me know," Beckman's attorney Noble says in a phone interview.

The two men knew each other for years. They met when the lawyer helped Beckman out of a drunk-driving charge and later continued to run in some of the same social circles. In many ways, Noble says, he could relate to Beckman. Neither grew up with money, and when they finally accumulated some, it could be hard to resist spending it in dumb, showy ways. Always the best-dressed attorney in the courtroom, Noble, like Beckman, owned Lamborghinis for a time; they were in the same luxury-automobile club.

Early on in the case, Noble suggested that nobody who could afford a $250,000 car was going to risk everything he had for a $27,000 ransom over some stolen weed. But as it turns out, Beckman did exactly that. Noble still can't figure it out.

"This case is the one case that keeps you up at night," he says.

Davis, the prosecutor, will remember it, too. He has no idea why Beckman did what he did. Unlike the movies, major dealers regularly write off losses of three or four times the amount stolen by Athanas as a cost of doing business, he says. The risk that comes with violence simply is not worth it.

"Their cost-benefit analysis was way off," Davis says.

He sees Beckman as a wealthy businessman who thought the rules no longer applied to him. Davis describes himself as a staunch believer in the social contract, the idea that we as a society are all better off when we collectively agree to do the right thing. The drug dealers or kidnappers or child pornographers who pass through the courtrooms operate outside of that contract.

"It just doesn't sit well with me," he says.

On the day of Beckman's sentencing, Davis was hanging out with the federal agents and cops who investigated the case, waiting for proceedings to start. The hearing had been a long time coming, and as they all piled into the elevator, Davis began telling the story of seeing that BMW with the TANCO plates a half-dozen years ago on I-64. Just as they reached their floor, he got to the part about how he said he was going to get that guy one day.

The elevator doors opened. Davis looked out.

"And guess what today is."

Editor's note: A previous version of this story provided inaccurate information about where John Davis glimpsed Todd Beckman speeding approximately six years ago. It was I-64, not I-44. We regret the error.