One morning, a federal prosecutor named John Davis was driving to his job at the U.S. Attorney's Office in St. Louis when he looked in the rearview mirror of his Toyota Yaris and spotted a BMW flying up behind him on Interstate 64.

Davis eyed the luxury car as it grew larger and larger in the mirror. When it blazed past him, the driver was a blur, but he immediately noticed the name on the vanity license plate — TANCO.

"One of these days, I'm going to get that guy," Davis said aloud.

For years, the career prosecutor had heard about Todd Beckman, the founder of a chain of tanning salons called TanCo. The perpetually bronzed CEO was a local success story, turning a tanning bed in the back of his father's beauty parlor into a small empire that extended across more than a dozen states. He opened not just tanning salons but massage parlors and gyms. In the coming years, he would debut yet another concept — a line of hormone and supplement centers, offering aging men the promise of recapturing their youthful vigor.

It was a lifestyle Beckman not only sold but embodied. Then in his mid-40s, he was a notorious playboy with blond highlights in his hair and a smile worthy of a toothpaste ad. He had a reputation as a hard-partying daredevil with a fondness for beautiful women, gaudy automobiles and anything that could go fast. He was even for a time a professional powerboat racer on the Formula One circuit, blitzing across waterways from Creve Coeur to the Florida Keys.

All that was fine, but it was Beckman's rumored side business, importing crates of marijuana, that interested Davis.

A month older than Beckman, the prosecutor had spent his federal career assigned to the Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Force, which focuses on large-scale narcotics conspiracies. Part of the job was talking to defendants who hoped to trade information on the bad deeds of others in exchange for shorter prison sentences. In those conversations, Beckman's name had come up often enough to make Davis suspect the tanning mogul was up to something more than peddling a year-round glow to strip-mall customers.

Agents from the Drug Enforcement Administration had also taken an interest in the flashy CEO, according to an agency official. So far, they did not have anything to present to prosecutors. Frankly, Beckman was a small fish compared to the major traffickers moving heroin, cocaine and mass quantities of marijuana through the metro area. And yet a supposedly legitimate businessman brazenly flouting the law had a way of annoying those responsible for enforcing it.

Davis watched the BMW and its TANCO plates speed out of sight. That was that.

But then, about four years later, in December 2016, the prosecutor was groggily watching the 4 a.m. news when the story of a vicious kidnapping caught his attention. A young Maplewood man had been abducted from his home, beaten and tortured for three days until his family paid a $27,000 ransom.

The names of four suspects — a pair of twenty-something brothers named Blake and Caleb Laubinger, 24-year-old Zachary Smith and 55-year-old Kerry Roades — meant nothing to Davis. But mention of the fifth made him sit up in bed.

"Did I just hear 'Todd Beckman'?"

Todd Beckman's marijuana arrived every month in shipments from California. An eighteen-wheeler would back up to the loading dock of his corporate headquarters at 11 Champion Drive in Fenton and offload crates of what appeared to be industrial toolboxes.

It was a good cover. The building, which included offices and a large warehouse, was the nerve center of Beckman's wide-ranging interests. Over the years, more than two dozen corporations have been registered there under his watch. Some fizzled, but others, including MassageLuXe and LifeXist gyms, had grown into multi-state franchises. The warehouse teemed with motorcycles, sports cars, racing go-karts or whatever else happened to grab Beckman's attention.

When a St. Louis Post-Dispatch reporter visited in 2010 for a profile of the successful entrepreneur, she noted walls covered with photos of him racing during his Formula One days, along with a "human-sized trophy" planted near his desk.

"You've got to be motivated," Beckman told her. "That's why I have all those pictures here. They're not just because I like to see myself. It's because it reminds me of winning."

With everything going on, no one was going to notice a couple nondescript crates arriving every four weeks.

It was Kerry Roades' job to handle the incoming cargo. A capable mechanic and generally handy when it came to building or fixing things, he had helped take care of the literal nuts and bolts of Beckman's big ideas for two decades. Once the crates were in the warehouse, Roades cracked them open and retrieved the true payload — between 50 and 80 pounds of marijuana in airtight packaging.

From there, the weed went to Blake Laubinger, a dull-eyed young drug dealer who started as an investor in one of Beckman's gyms and became an awestruck protégé. Laubinger stashed the pot at his house in the small town of Pacific, Missouri, parceling it out to a network of low-level dealers and then collecting the proceeds from their sales. He and Beckman split profits of about $800 per pound and sent the rest back to their supplier in California. On an 80-pound shipment, they could each clear $32,000, maybe more if the market was good.

The operation hummed along month after month until October 2016, when Laubinger returned home to find his house had been burglarized. The 24-year-old searched desperately, but it was just as he feared — his safe with $15,000 and 24 pounds of marijuana was gone.

In a panic, he called both Beckman and his older brother, 26-year-old Caleb Laubinger, and told them what happened. He even called Pacific police and reported the burglary, although he wisely omitted the bit about the missing marijuana and drug money.

Both were problems. Not only had Blake Laubinger fronted his network of dealers — putting up the weed on the promise of being paid after they sold it — but Beckman had fronted him. Forget about profits; he was now in debt tens of thousands of dollars to the tanning mogul, and he worried about the consequences.

"I mean, it wasn't a good situation," Blake later told prosecutors. "There was a lot of money lost, and I had no way of paying it."

In the short term, he says, his brother loaned him $75,000 to buy time. (Caleb Laubinger claims it was only $3,000.) But the only real solution was to find the burglar and get their money back.

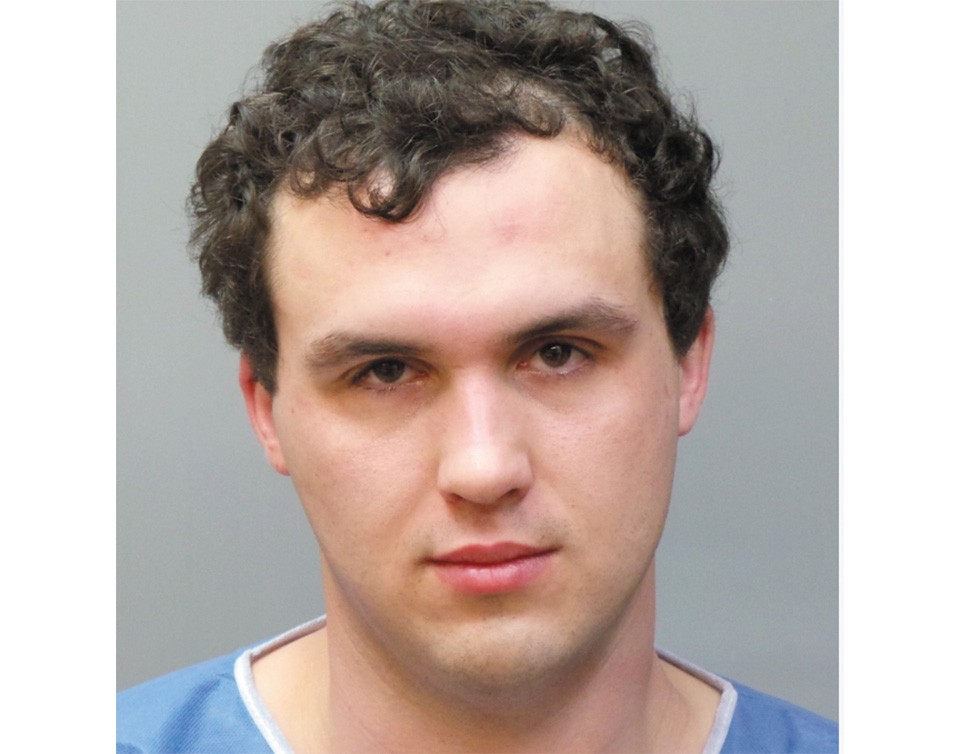

Luckily for Blake, he knew exactly who had ripped him off. A fellow drug dealer, Ellis Athanas III, knew where Blake kept the marijuana and had easy access to the house, because the two 24-year-olds had been literal partners in crime ever since meeting in 2010 at St. Louis Community College. Both were student drug dealers at the time and decided to team up.

Athanas had long, light brown hair that hung past his shoulders, contributing to his surfer-bro vibe. He had met Beckman just once (when the middle-aged entrepreneur complained of an aching back, Athanas suggested they go to hot yoga together), but he knew when the shipments were incoming. After all, he was one of the people who had helped sell them.

Athanas had been peddling marijuana since he was about sixteen years old but recently had grown more interested in daring drug ripoffs. "Seizing dealers' assets," is the way he described it.

Blake Laubinger had teamed up with him on a few such escapades. Athanas would arrange to meet another seller in an out-of-the way location, snatch the drugs and speed off in his car. Blake, parked just out of sight, would wait until his partner passed and then pull his truck across the road, cutting off any pursuers.

Now, he discovered, he was the one whose assets had been seized. And his former accomplice was on the run.