Forty years ago this week, state and federal officials in Missouri issued a dry document to announce a grand ambition.

In a 43-page proposal dated February 7, 1977, they stated their aim to blaze a footpath through the Ozarks, the rugged highlands that roll across southern Missouri. It wouldn't be easy. The native flora, fauna, terrain and certain human occupants made that area, for hiking purposes, hostile territory.

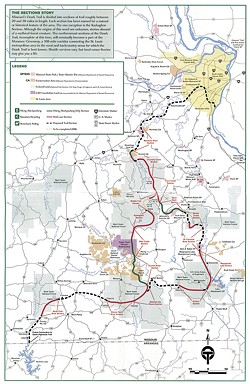

The planners envisioned an "Ozark Trail" that could start near St. Louis and snake its way south over the region's hills and hollers toward Arkansas, using as much public land as possible. An eastern spur would swing across Johnson Shut-Ins and Missouri's highest point, Taum Sauk Mountain.

The state felt pressure to deliver such a corridor. In places like St. Louis, hiking was booming. Folks now enjoyed the requisite free time (thanks to labor reforms) and mobility (thanks to automobiles and interstates) to wheel out to the countryside, tramp around and breathe the forest air.

The only problem? There wasn't enough trail. In 1975, the state's Department of Natural Resources found that Missouri had 655 miles, but needed twice that to meet demand. That same year, the DNR hired Fred Lafser, an avid hiker and map-hoarder in his mid-twenties, to help solve the problem.

Sitting in the Jefferson City office building where he worked as a recreation planner, Lafser began to pore over official maps. He quickly discerned a viable route through the Ozarks.

"It evolved over a few hours," he recalls.

In the year that followed, he pitched his idea to federal and state agencies. They liked it, and collaborated on the February 1977 proposal, an open-ended blueprint for what Lafser called "an immensely complicated coordination project."

"The trail is crystallizing," Lafser wrote in a letter at the time. "Considering how rare it is for two agencies to agree on anything, agreement of eight agencies for a cooperative effort was a landmark achievement!" Private groups such as the Sierra Club allied with the government to form a coalition: the Ozark Trail Council.

Had their momentum continued, the Midwest would now have an answer to the Appalachian Trail or the Pacific Crest Trail, made famous by Cheryl Strayed in the bestselling Wild. Like those "through-trails" — meaning end-to-end paths, not loops — the Ozark version could have served as a magnet for tourists, and their money.

That's not quite what happened, though it looked promising at first. Volunteers started clearing brush and adding miles. In the spring of 1980, Missouri officials met with counterparts from Arkansas, where an Ozark Highlands Trail was already under construction in the state's scenic northern half. Together they dreamed of joining the two paths for an epic 700-mile track.

"There's no question that this trail will draw people from Chicago, from Texas and from all over the Midwest," Al Schneider, the DNR's trail coordinator, told a reporter in 1980.

The DNR held a dedication ceremony in October 1982 at Owl's Bend, a spot on the Current River near a new trailhead. The incipient Ozark Trail, Lafser told attendees, could offer "long vistas atop glade-laced mountains, delicate spring wildflowers, gold and red hillsides during fall's colorful display, placid streams nestled between the hills and winter's fairyland of ice-glazed trees and snow-covered earth."

The "ultimate objective," Lafser continued, was to develop "350 miles of the most beautiful trail in the country." Ninety miles had already been built in only five years. At that rate, the trail should've been finished by 1997.

But the Ozark Trail remains unfinished today.

It's not that demand for hiking trails has flagged. According to the DNR's most recent citizen survey, "trails are the most popular type of outdoor recreation facility in Missouri and the one that residents most want to see increased."

And it's not that nobody's working on it. Distracted by tight budgets and other priorities, the government stepped back, but a core of dedicated volunteers has filled the vacuum. They maintain the thirteen sections built so far, which add up to 338 miles of the roughly 500 now envisioned.

No, the Ozark Trail isn't finished, and perhaps never will be, because the last third is the most daunting: The trail must somehow traverse seven gaps of mostly private property — a combined 162 miles through eight different counties — and in a region that has historically cast a suspicious eye toward government, outsiders and recreation projects.

Not all Ozarkers are hostile. Some small towns are even clamoring to link the trail to their borders. Rather than see it as a threat, these regional leaders see the Ozark Trail as an opportunity.

"It's a gradual process of changing attitudes," says Roger Allison, board member of the Ozark Trail Association, a volunteer group that extols the economic virtues of connecting to the trail. "But it's the Show Me State. You've really got to show people sometimes for them to come around to it."

The so-called "Ozark mountains" of southern Missouri aren't mountains, and never were. Between one and four million years ago, this plateau rose and wrinkled. As streams carved out canyon-like valleys, rain and snowmelt seeped into the dolomite and limestone, crafting thousands of caves, sinkholes and springs.

In 1818, a 25-year-old New Yorker named Henry Rowe Schoolcraft walked these hills and took notes. He beheld much the same region that the Osage tribe and their predecessors had roamed for at least 9,000 years.

"Deer bounded on frequently before us," he wrote, noting how black bears hid in trees, elk wielded "enormous" antlers and wolves howled after dark. He climbed up to "stony precipices" and looked out on miles of pine, hickory and oak. Resting in caverns where his campfire light flickered on the rock walls, he pondered "the mysterious connection between the Creator of these stupendous works and ourselves."

This reverence for nature, soon to infuse romantics such as Henry David Thoreau and John Muir, would inspire the U.S. government to cordon off enclaves, such as Yellowstone and Yosemite, as national treasures.

But when the feds looked to the Ozarks a century later, it wasn't to preserve beauty. Quite the opposite: It was to heal a wound.

The first white settlers had come to the Ozarks from southern Appalachia in the early 1800s. Mostly of Scots-Irish stock, they initially claimed the fertile valleys. At mid-century, though, more folks came and settled on the slopes and ridges. The soil was rocky, but they found that if they just torched the forest and underbrush, they could let cattle and hogs range free. Fires roared regularly, denuding the earth.

The woodland absorbed another blow a few decades later, when logging firms harvested trees in massive numbers. By 1900, the Ozarks' virgin forests were gutted; by the Great Depression, the situation was bleak. Bankrupt families squatted on ground abandoned by lumber companies.

President Roosevelt's Forest Service concluded that almost eight million acres had fallen into waste, but if bought and managed scientifically, it could regrow. Missourians were suspicious of a government land grab, but also desperate. The state legislature enabled the purchases.

The handover was tense. Historian Will Sarvis wrote that hardy and self-reliant Ozarkers showed not only "low rates of formal education and literacy" but also "a warrior mentality that manifested itself in a tendency toward combativeness."

According to a Forest Service account, the squatters viewed the land purchases of the 1930s as "unwarranted government interference."

"It was not unheard of for a squatter or tenant to meet the threat of eviction with a rifle in his hand," the agency wrote. "Even a visit by Forest Service personnel could evoke a violent response."

And the Ozarkers clung to their custom of woods-burning. Seeking to set an example, the government prosecuted fire-starter Lynn Crocker in 1936. He got a six-month sentence, but not for starting the blaze; rather, he was convicted of breaking two of the federal officer's ribs during his arrest.

Within six years, Washington amassed 3.3 million acres into giant blocks. Four of them were christened the Mark Twain National Forest in 1939. (Other names floated: "Mozark," "Ne-ong-wah" and "Hill Billy.") The Civilian Conservation Corps planted trees, and the woods did grow back. Decades later, these wooded tracts would provide the islands of public land through which volunteers ran sections of the Ozark Trail.

But as the Forest Service gradually gained acceptance, a different federal agency landed with a jolt.

In the late 1950s, activists grew worried for the future of America's free-flowing rivers. So in 1964, Congress and President Johnson created the first federally protected riverine park: the Ozark National Scenic Riverways, a picturesque 134-mile stretch of the Current and its tributary, the Jack's Fork.

The legislation tasked the National Park Service with managing not just the water, but also 300 feet on each side — including 64,000 acres of private land. "Scenic easements" allowed private citizens to keep ownership near the riverbank, so long as they agreed not to develop it. Many landowners took the deal.

For those who resisted, the park service had a mandate to acquire. Early on, certain dishonest federal agents bullied landowners into accepting low-ball offers, Sarvis found. When holdouts wouldn't budge, the government used eminent domain, seizing more than 200 parcels.

The government's small budget and shortage of experts meant that appraisals came in low. Federal courts often remedied that by awarding Ozarkers higher amounts, but that was cold comfort. Resentment festered. Some residents responded with vandalism and arson.

"Native landowners," Sarvis wrote, "rather generally disparage the government as their enemy."

While this drama was still playing out, activists at the state level tried to push further: In 1969, they announced a petition drive for a ballot initiative to protect an additional 850 miles of 20 different Ozark streams. They proposed no land acquisition, just scenic easements.

The reaction was explosive. One opponent told a Post-Dispatch reporter that it was "not altogether impossible" that float-tripping canoeists might take a bullet in the head.

J.C. Yocum, a member of an opposition group in Crawford County, was quoted as acknowledging a possible compromise, but added, "It just seems to us that a bunch of outsiders, city people, have come down here in our backyards and tried to tell us how to run our land. We aren't going to let that happen."

An unnamed cattle rancher was more blunt. Referring to the chairman of the ballot initiative, Roger Taylor, he told the reporter: "If this thing passes, Taylor'll be the first one shot."

At 11:30 p.m. on April 27, 1970, a stick of dynamite exploded under Taylor's car, which was parked outside his St. Charles home. No one was injured, but the bomb destroyed the car's interior and shattered windows in his house. Another scenic rivers campaigner reportedly received a phone call soon promising, "You're next."

Two weeks later, the activists shut down their petition drive.

From the outset, the public-private Ozark Trail Council proceeded gingerly. They forswore eminent domain. Any landowner willing to participate, they felt, should himself dictate permissible use of his section — be it solely hiking or bicycling and horseback-riding as well.

The council didn't lobby small Ozark municipalities at all. They preferred direct chats with landowners — and a low profile.

"I'm nervous about user groups getting too publicly excited too soon about the Ozark Trail," Fred Lafser wrote in a February 1977 letter. "The last thing the landowners need to see is a proposal in the newspaper for a long trail for city recreationists."

Lafser wished to include Ozarkers in any decision-making. "It is essential that these people have a chance for input and a chance to hear the facts before they begin to hear rumors," he wrote.

The council showed no such hesitation when it came to public land. In fact, to push the trail closer to St. Louis, they tried to piggyback onto an unrelated federal project — but their plan backfired.

In the late 1970s, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was planning to dam the Meramec River near Sullivan, about 65 miles southwest of St. Louis. The corps' primary goal was flood control, though the resulting 12,600-acre lake would have also been open for fishing, swimming and boating.

The Ozark Trail Council sought to insert the trail into the corps' master plan. The logic was laid out by Gerald Stokes of the federal Bureau of Outdoor Recreation in a letter he wrote to a fellow trail supporter.

If the dam gets built, he explained, the trail gets a green light along the Meramec. But even if the dam project collapses, perhaps the trail aspect could survive with the next owner. The Ozark Trail, he wrote, "should be completely compatible with the 'alternative,' no matter what that ends up being."

That was a miscalculation.

A zealous coalition of wilderness protectionists and property holders inside the footprint turned public opinion against the dam. They doubted its benefits and decried its costs: Not only would the lake inundate a scenic river valley and Onondaga Cave, but it had already displaced families in the flood zone, some via eminent domain.

In August 1978, a majority of voters rejected it.

That left the feds with 28,000 acres to unload. Most went to auction, but Congress conveyed more than 5,000 acres to the state of Missouri, along with two easements. One was a scenic easement along the Meramec of 300 feet on either side. The other — encouraged by the Ozark Trail Council — would in essence grant permission to run trail inside those ribbons of land.

In 1982, Missouri's General Assembly accepted the scenic easement, but barred the state from blazing the trail inside it. As former state parks director John Karel recalls it, area legislators had to placate constituents still resentful of the government seizures.

Fairly or not, the state's attempt to leverage the dam debacle to establish a trail, Karel says, "was seen as a very sneaky thing to do."

As it stands today, the 1982 law does not ban the Ozark Trail along the Meramec River. It appears to only bar the state from involving itself in such an effort there. Trail volunteers could make it happen, but they would have to obtain their own separate agreements with landholders.

Says Karel: "I think that's been a crippling blow to the completion of the Ozark Trail."

By the late 1990s, the Ozark Trail had broken the 200-mile mark, but some parts languished — including the corner of Mark Twain National Forest near Potosi, where Paul Nazarenko labored as a recreation technician.

"It was pretty much a brush patch," Nazarenko recalls. The trail council occasionally held meetings, he recalls, but didn't do much else.

So Nazarenko wasn't surprised in the summer of 1997 when a thirty-something St. Louisan named John Roth called. Roth complained that the Trace Creek section was overgrown. Nazarenko suggested he come in person to help him clean it up.

That Saturday, Roth showed up — in loafers, out of shape, an awkward city-slicker. But the two quickly became friends, and Roth kept returning. Within a few years, Roth had sold his computer consulting firm and began commuting daily to trail-build — just for fun.

"Building a trail is not brain surgery," Nazarenko recalls fondly, "but John used to treat it like that. He wanted it to pass the prettiest locations it could. We spent a lot of time arguing out there."

And then Roth dove deeper.

Even the nation's most prestigious through-trails — including the Pacific Crest and Appalachian — rely heavily on volunteer groups. Roth realized the Ozark Trail at the time had no such support.

So he linked up with John Donjoian, founder of the Gateway Off-Road Cyclists, a 501c3 in St. Louis that knew how to build trail and get grants. In March 2002, Roth and Donjoian met with the Ozark Trail Council to propose using that same model to set up an all-volunteer Ozark Trail Association.

"The land managers were thrilled," Donjoian recalls, "because they didn't have a budget to build trail. They barely had budget to take out the trash."

In short order, John Roth recruited an army.

"He'd get you to do work that your spouse never could," says Kathie Brennan, the association's president. Roth was convinced that a steady trickle of helpers was ineffective. Better to lure a locust swarm of volunteers for a work weekend by promising free meals and camping. Charming and gregarious, Roth reveled in these events, called "megas," which sometimes drew more than 100 people from several states.

But tragedy struck on July 3, 2009. Roth was operating a tractor on his Crawford County farm when a tree fell, killing him.

After the initial outpouring of grief, the volunteers realized how much they'd depended on their founder. "We went into crisis mode," recalls Brennan. "We thought, 'Are we going to be able to get through this?'"

And yet they did. While the Appalachian Trail Association boasts 50 full-time staffers and a budget exceeding $8 million, the Ozarks version has only one such employee, and $133,000 annually to work with — most coming from government grants and private donors such as REI and the volunteers themselves.

Still, every year the Ozark Trail Association adds miles and raises funds with a 100-mile mountain bike race. Nearly the entire trail has been "adopted" by caretakers who clear their sections.

To understand why these people devote so much free time to a rocky footpath, one need look no further than the association's online forum, where hikers swap stories. They record encounters with hog-nosed snakes, feral hogs, baby raccoons, gangs of turkeys "exploding into the air" and moonlight serenades by an "owl choir."

They speak of strange sights: "Approaching each stand of pines gave an almost ominous feeling," wrote one contributor, "as if the trees were absorbing light instead of reflecting it."

The place names they mention, such as Devil's Run or Gunstock Hollow, suggest hidden histories. An entire section is named after the "karkaghne," an elusive cryptid said to prowl only the deepest woods, eating limestone and causing havoc.

Many hikers note on the forum how unexpectedly grueling the Ozark Trail can be. The highest peak is only 1,772 feet, but the constant up-and-down taxes legs, while the rocky terrain slows the pace. The association knows of fewer than 100 hikers who have conquered the "backbone," the continuous stretch of 230 miles from Crawford County to Oregon County.

Chiggers, ticks and spiderwebs terrorize summer hikers, who must also avoid poison ivy and bramble. The winter has its own perils: In January 2013, a father and two sons got lost on the Ozark Trail during a rainstorm in Reynolds County and died of hypothermia.

"A big part of why the Ozark Trail is important is that remoteness," says Donjoian. "You're out in the backcountry."

Of course, one man's backcountry can be another man's backyard. One forum contributor recalled a New Year's Eve along the trail: "We had long since settled into our tents and gone to sleep when the new year came in, but several shotgun blasts and the unmistakable sound of automatic weapons fire from the ridge above our camp reminded us that Missouri is home to all kinds of interesting culture."

If the Ozark Trail ever becomes whole, it must bridge seven gaps of mostly private land. One such gap — about 25 miles as the crow flies — spans the hills between the hamlets of Thomasville in Oregon County and Pomona in Howell County.

The most scenic route would hug the Eleven Point River. But that might require passing through properties like Eleven Point Ranch, an 11,000-acre cattle and timber farm.

"I'm not dead-set one way or the other," says Nancy Shaw, whose family owns the farm. She fears that welcoming the trail would necessitate altering their fencing system, as well as interfere with how they rent out the property to hunters, which helps to pay the bills. "We live a quiet life, and to think you have all these people running around on your land. Are they going to be good stewards or not? We've had stuff stolen as it is."

Ken Kurtz, an Ozarks Trail Association board member, says fear of marauding hikers is common in the region — but misplaced.

"The truth is that hikers are more likely to pick up trash and haul it out than to leave it," Kurtz says.

This conception of hikers as eco-friendly tourists eager to plunk down dollars in small towns is one that the trail association actively promotes. It has resonated in south-central Ozark counties, which show some of the lowest median household incomes and highest unemployment rates in Missouri.

A finalized through-trail, backers believe, would lift the local economies it beads together. Perhaps the best analogy, they say, is the Katy Trail, the railroad-turned-bike-path that runs 237 miles across Missouri's midsection. According to a 2012 state study, the Katy Trail generates $18 million in revenue annually. It has boosted several towns in its path, including Augusta, Hermann and Rocheport.

There is no study that gauges the Ozark Trail's current impact. But the Ice Age Trail, a proposed 1,200-mile footpath across Minnesota and Wisconsin, is only partly complete, just like the Ozark Trail. A 2012 analysis concluded its combined 600 miles draw 1.2 million visitors each year, who inject about $113 million into statewide and local economies. A completed trail would surely have an even bigger impact.

Says Stuart Macdonald of the non-profit American Trails Association, "I think the most interest is in the 'brand name' trails that enable a multi-day journey."

In January 2016, the Ozark Trail Association presented its case at a workshop in the Arcadia Valley, where the towns of Ironton, Pilot Knob and Arcadia cluster among the hills of Iron County. The chamber of commerce was so impressed, it created a business owners' group to explore trail options.

Ironton mayor Robert Lourwood says he has personally lobbied landowners to sign off on a connector path to the Ozark Trail. He reports verbal commitments from four. "Even if hikers stay for just one night, buy two meals, go to the grocery store to buy provisions, it's worth it," Lourwood says. "I'm not looking for a grand solution; I'm looking for pieces of a puzzle."

Further southwest in Carter County, the Van Buren Chamber of Commerce has tried for years to lay a network of local trails. They want a path connecting their town center to Big Spring, one of the nation's largest springs, a tourist draw about five miles south of town. The chamber's hope was to get this path incorporated into the Ozark Trail.

Some stakeholders in that gap, however, don't want their land used as a conduit. Cattle farmer Gary Norris fears (among other things) that an easement would crater his property values.

"I can't think of a farmer around who'd be for this," Norris says. "Farming's hard enough if everything's going as well as it can be, but you put up other obstacles, it's even harder."

Adds merchant Mitch Terry, "We're not opposed to trails, we're opposed to them going through our front yard." After all, he says, the river has attracted "the party crowd" to Van Buren. "Makes you think maybe the trail will be like the river."

And for some locals, a rise in income is beside the point. Rebecca Landewe, a project manager in Van Buren with the non-profit Nature Conservancy, says that Ozark residents share a profound identification with the land.

"A lot of the reason people like living here is that you can be left alone," observes Landewe. "So the idea of inviting a bunch of strangers to walk across your property probably doesn't sit well."

Growing up in Pacific, at the southwestern tip of St. Louis County, Steve Myers loved visiting Jensen's Point, a stone pavilion perched on a bluff with a panoramic view of the Meramec Valley. As a boy, Myers ate cheeseburgers there with his mom. Now he's an alderman who envisions his town below as a hiker's hub, offering access to both the polished network of St. Louis-area trails called the Great Rivers Greenway and the more rustic Ozark Trail.

Out of the seven gaps left to fill, this 39-mile stretch between Pacific and the Ozark Trail's northern terminus at Onondaga Cave State Park is the largest. But Myers insists on its feasibility — and believes a full through-trail will hold an allure that disjointed sections won't.

"There's a lot of pride in hiking the Appalachian Trail, for example," Myers says. "People may not hike the whole thing, but they can say they were on it."

If Myers is to fulfill his dream, he'll need allies. A year ago, he met with J.T. Hardy, city administrator of Sullivan, which lies in the gap. Hardy studied a map and discovered a way to bring the trail's northern terminus eleven miles northeast to his town's boundaries. He would just need to win over a half-dozen landowners, and establish a spur to Sullivan.

He would also have to rely on gravel roads as connectors. They are less scenic, so not ideal. But the Ozark Trail wouldn't be alone in resorting to this measure. The Ice Age Trail uses them too.

The result, Hardy believes, could benefit Sullivan. "To me it's totally conceivable to have it done, if someone wanted to spearhead it," Hardy says.

That "someone" has failed to surface in government for decades. Since the 1980s, no state agency or official has led the charge to completion — perhaps because so much of the trail winds through federal land. Or maybe they have more pressing problems. True, former Governor Jay Nixon did steer federal grants toward the Ozark Trail, and one of his last acts in office was to create three new state parks, including a namesake park in Reynolds County, accessible by the trail.

But Nixon apparently spent no political capital trying to extend it. And Governor Eric Greitens' office didn't respond to questions about whether he would prioritize it. It's likely not even on his radar. So today, in the trail's fortieth year, "there's a dearth of statutory authority," says former association president Roger Allison. No legislation protects or authorizes it.

And for the volunteers, completion is a long-range effort. They're still feeling their way forward.

"As trail guys, we're a little shy," Allison adds. "We don't usually go around asking people for easements. But who knows, we may be pleasantly surprised."

Fred Lafser, the trail's original visionary, believes the right messenger with the right message could break the 40-year logjam.

"At some point somebody will come along — a DNR director or a governor — and it will happen quickly," Lafser says. "But if nobody's supporting it, it will take a while."