In "Not a Threat," Nat described her concerns about the lack of communication between the many offices tasked with ensuring student safety on campus.

Her nightmare began in February of her junior year. Her friend's ex-boyfriend, someone she'd considered a friend, drank too much at a bar. When she tried to take take his drink, he grabbed her hand and twisted her wrist until it was sprained. Later that night, he refused to leave her apartment until she dialed the police. Still, they fell in and out of contact, and in October, she says he sat on her at a party, choking her until she passed out.

She reached out to his residential advisor, who she believes reported his dangerous behavior to a superior, but Nat never heard anything about it again. In February, Nat's friend, his ex, overheard him plotting her own murder.

The Washington University Police Department was summoned. Over the next few days, Nat says that she and several other individuals went to the Title IX Office. Nat also gave a statement to the campus police.

The Title IX Office informed her that her case constituted physical, not sexual, assault. Both Title IX and the campus police indicated the case was a more appropriate fit for the Office of Student Conduct. A week or so later, she says, she received a phone call saying that Student Health Services had evaluated him and deemed him "not a threat." She says the campus police told her that her file had been passed along to Student Conduct.

Nat says she called Student Conduct several times over the next few months, but never heard back. This April, she learned that an underclasswoman had accused the same man of rape. That was when she decided to go to the Student Conduct office. Yet when she inquired about the status of her case there, she says they'd never heard about it.

"It was a major failure in communication," she says.

Exasperated at this disjointedness, distrustful of the offices she had sought out for support and wanting immediate answers, Nat began writing her article that night, April 10.

"The day that article came out, I got a notification that he had been removed from campus," she says. "The day that article came out. Not a day before. Not when I went into the Office of Student Conduct. That day."

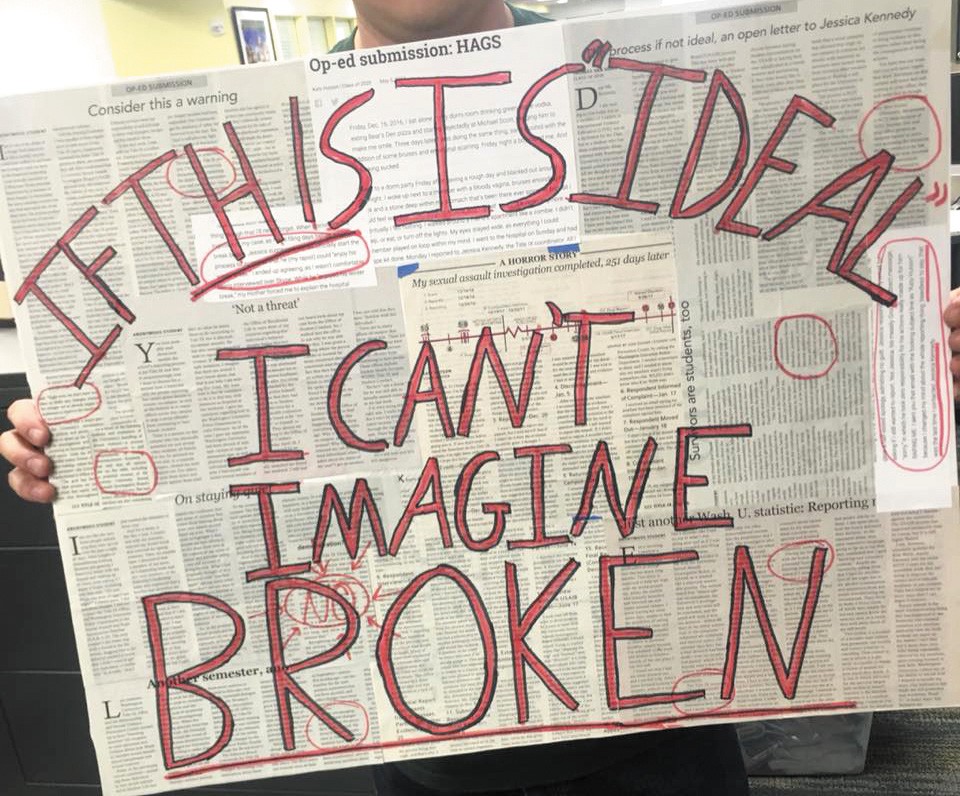

But the movement she'd unexpectedly launched didn't stop with Nat's case. In the coming weeks, other students' personal essays flooded Student Life's editors' inboxes.

"We knew that there was still work to be done and we regularly assess the process, assess how our investigations are going, we seek feedback, so that was some very pointed feedback we received in those op-eds," Kennedy says of the outpouring.

The essays were harrowing.

The day after Nat's piece was published, Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs Lori White wrote about her own sexual assault in "My Heart Sank ... Because I Understand." "On Staying Quiet" was about a girl who wondered if she'd been drugged before her assault at a fraternity from which she was later blacklisted. "Survivors Are Students Too" tackled systemic difficulties students faced after assault on campus. Then, the day of the rally, "Three Weeks Later" debuted, written by a freshman who alleged that Nat's assailant had raped her.

"While I only found out about his history afterwards, Washington University had multiple reports about this student and was aware of his violent tendencies long before my assault," the young woman wrote. "He was the subject of the Student Life article 'Not a Threat,' and I am the freshman that he raped. Washington University failed. They failed to protect its students, and my rape is a direct consequence. If they had taken action earlier, this would not have happened to me."

Part of the problem, Nat believes, is that everyone knows the Title IX Office is ineffective. If survivors know how difficult and frustrating the reporting process is, why would they bother to make a report?

In the 2015 Association of American Universities Campus Climate survey, 22.6 percent of Wash U's female undergrad respondents said they'd been subject to some form of nonconsensual sexual contact. Between 2014 and 2016, 62 reports of rape were made to the Washington University Police Department. Yet in the 2014 to 2015 school year, only five Wash U students opened Title IX investigations. In those cases, three respondents were found responsible.

In 2016-17, that number jumped to thirteen, with six found responsible (one case was withdrawn by the complainant).

Hannah*, the author of a May 1 op-ed, "Victim of the Gray Area," chose not to report her incident. The junior says she had never previously met anyone via Tinder, but in January, decided to meet up with a fellow Wash U student she'd swiped on the app. The first date, she recalls, was enjoyable. The two watched a movie and kissed. Eventually, the relationship progressed into a sexual one. The two decided to keep it at the "friends with benefits" level.

One night, after going to a party, Hannah went to her Tinder connection's fraternity. All she remembers is talking, with clothes on. Yet she woke up naked next to him that next morning. She rushed to class, but that night, she stayed in and cried.

Hannah believes there was a lot of "gray area" in her case; they had had sex and been on dates previously, and she was drunk. Plus, she points out that hookups are almost "expected" at fraternity parties. Had she consented that night? She wasn't sure if what happened was "real assault."

"It took me a little bit to realize that I was uncomfortable with what happened," she says. It was only after a friend told her the situation was not OK that she began to process it. "It was only after she said it to me, I realized, 'I don't feel comfortable.'"

Hannah contacted the boy two days later, and he walked her through his recollection of the night. He wasn't sure why she was uncomfortable — they'd had sex before.

"He said that I was apparently too drunk to walk home so that's why he had me stay there, but according to him, I was saying that I wouldn't stay unless we had sex," Hannah says.

Just as Nat fears, Hannah felt deterred by the Title IX reporting system. Hannah remembered reading in Student Life about a freshman who reported assault right as winter break began. In the piece, published in May 2017, a freshman wrote that the director of the Title IX office suggested they delay the reporting process until spring so that her rapist could "enjoy his winter break."

"That story stayed with me," Hannah recalls. "I was like, 'If they didn't take that seriously, why would mine be taken seriously?'"

Even if she wanted to report, Hannah says, she wouldn't know how. At the time of her assault, Hannah was seeing a university counselor for unrelated issues. When she mentioned the incident, she says, the counselor said she didn't know much about the process and would have to look into it. She told her counselor not to bother; the therapist didn't press further.

Of her Tinder boy, Hannah says today, "I just don't know if he did this maliciously or not, so I don't know if I want to classify it as sexual assault, even though I know the definition of it doesn't need to have any sort of intent on his part. But I still kind of struggle with that."

When the op-eds began pouring in, Hannah saw an opportunity for closure.

"I felt guilty about not reporting it because of how many people experience sexual assault on campus. And me not reporting means another case that goes uninvestigated, another one slips through the cracks and gets away with it and doesn't have repercussions," she says. "So I felt like this was my way of doing something I was comfortable with, where I'd be able to remain anonymous but still put it out there and let it be known to the community that this happened."

In her piece, "A System Where You Can't Win," junior Maddy Yaggi chose to use her real name. She was tired of hiding. Published May 3, the op-ed divulged her experience living on campus just after her rapist was expelled.

Yaggi says she was raped after a Super Bowl party during her freshman year, by someone she had been casually dating. She woke up the next morning, confused and bleeding from both her vagina and her anus.

After later talking it through with friends, she says, she concluded that she was either unconscious, asleep or blackout drunk during the assault. "I'm still not positive which of the three it was," she says. She had memories of her head hitting against things (the wall, a shelf, a dresser). "When my head hit, I would snap back into it for a second and I would have a couple seconds [awareness] of what was happening," she says. "And then I would be blackout or asleep or too drunk again and then not come to until my head hit against something else."

Yaggi wasn't sure what to make of the incident until others explained it could be rape. After a semester of trying to cope — running for miles on end, drinking and partying more than she ever had, avoiding romantic and sexual relationships — she contacted the university's Relationship and Sexual Violence Prevention Center and got a no-contact order. When she returned to school in the fall, she decided to report.

It was a nightmare, she recalls. In one instance, after she and her assailant provided their responses, she received no warning other than an email saying the responses would be available for viewing in 30 minutes. Yaggi had no time to get into the right headspace. Although she had a biology exam just an hour later, she read the response anyway. She had to know what it said.

"There was really no regard for how traumatic the reporting process actually is," she says. "That really solidified it for me. I bombed that test. I couldn't focus at all."

Another exam fell a day or two away from the release of the final panel decision. She asked for an accommodation, but her professor refused. Ultimately, he gave Yaggi a zero on the final. She now has to retake the course.

The crux of Yaggi's piece, however, is what happened after all that. When her rapist was finally expelled, he had two weeks to file an appeal. He waited until the last minute, granting him another two weeks on campus. Because he had received the highest punishment, expulsion, Kennedy told her the university could not punish him further for any actions he committed during the appeal period.

During that month, Yaggi wrote in her op-ed, she feared he would retaliate. When she expressed this worry to the Title IX Office, she wrote, she was told that if she felt unsafe, she should call the campus police. The offer simply felt like the function of the police: You feel unsafe, you call them.

In reality, he was living off campus that entire terrifying month, but Yaggi was never informed. The Office of Residential Life was aware he had moved out, but the Title IX Office wasn't, Yaggi wrote. She saw it as evidence of poor communication between different university offices.

Yaggi's op-ed came at the end of the wave, after the rally.

"I was just so inspired by everyone else who was coming forward and saying their stories and what they went through, but what I thought was missing from that was that even if they made the changes they were advocating for, there are still fundamental problems with the system," she says. "So a lot of what I saw calls to action for were 'We need to fire Jessica Kennedy' or 'we need to get more cases reported or settled in favor of the survivor,' which seem to me like simple answers that wouldn't get at the root of the problem. So I wanted to tell what happened to me even after I won my case, even after he was expelled. It's not one person's fault or a statistical issue. They need to fundamentally rethink this whole thing."