No one was supposed to know she was there.

On Tuesday, April 17, at midnight, Nat* quietly packed a bag of clothes, a few books, her backpack and, with permission from Washington University's Office of Residential Life, the small shelter cat she felt she couldn't leave behind. She would spend the remaining five weeks before her college graduation not in the off-campus apartment she had shared with friends for a year, but here, in a secure, secret suite on campus.

Her new place was designed for two, so Nat had a lot of room to herself. It was a bare, white space, the walls devoid of the photographs and posters typical of a college dorm room. Just Nat, the cat and her few bags.

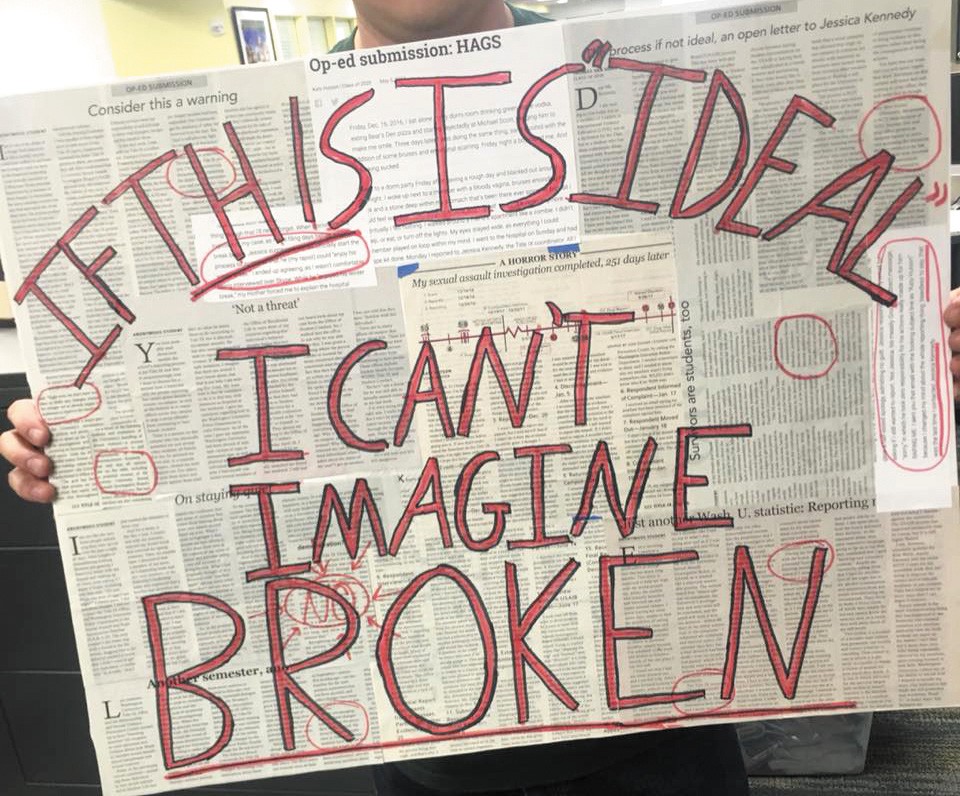

That was, of course, barring the expansive collection of newspaper pages carefully arranged on a small entryway table. In her final weeks of college in this empty, foreign space, this display was what Nat clung to most. When Nat decided to anonymously publicize her story about surviving assault in the campus newspaper, Student Life, she never anticipated that its pages for the remainder of the semester would brim with fellow survivors' stories.

As the drama of the ensuing weeks unfolded, the display served as a visual reminder that she had, almost accidentally, sparked one of the largest student movements the university had ever seen, one that would garner media attention, contribute to a national dialogue on sexual assault and culminate in a rally with hundreds of attendees.

And when it started to feel surreal to the mild-mannered, intellectual girl in the center of it all, that collaged entryway table was proof.

"By the end of it, I had the entire [table] covered in different pieces of newspaper sitting there. There was something tangible about that," Nat says. "I was like, 'Look at this. Look at the effects of things. Look at the echo.'"

Nat's essay, "Not a Threat," arrived in Student Life Editor-in-Chief Sam Seekings' inbox on April 10. He was in the midst of a busy semester studying psychology abroad in Copenhagen.

"Obviously reading through it, looking at it, it was a very, very serious piece and I think we took it very seriously for that reason," Seekings recalls.

Seekings limited initial knowledge of the op-ed to himself and two managing editors. For the next six days, the three engaged in a series of tough discussions.

"I was thinking about the same questions that a lot of journalists and journalism publications go through," Seekings says. "Is this something we should publish? Is this something we should publish anonymously? Can we verify various things in this? If so, how are we going to do that? Is this feasible? The time frame, that kind of thing."

By the time Washington University's almost 8,000 undergraduates woke up the following Monday, the 616-word account was live on Student Life's website. In it, Nat alleged that there was a serial assailant on campus, one whom the Office of Residential Life, the Title IX Office and Washington University Police Department had all received reports on over the course of several months. She wrote that he'd physically attacked her, yet the campus bureaucracies seemed incapable of responding. She'd written the op-ed, she wrote, after learning that another female student had accused the young man of rape.

On the day her story came out, Nat was eating lunch at a campus dining hall. She glanced at her phone. There was a message from a friend who knew she had authored the piece: "You should know there's 200 people in a GroupMe organizing a rally about this. Do you want me to add you?"

Nat rose from the table mid-conversation, her dining companion watching in confused silence as she walked to a nearby pile of Student Life copies and, returning to the table, flipped to the article, which she passed across the table to her friend. As she read, her friend's eyes grew wide.

Nat joined the GroupMe texting group, which had been started by women in the Alpha Phi sorority. That evening, the chat reached capacity at about 600 members.

"People were just talking and it was great. It caught fire," remembers Rachel*, then a sophomore.

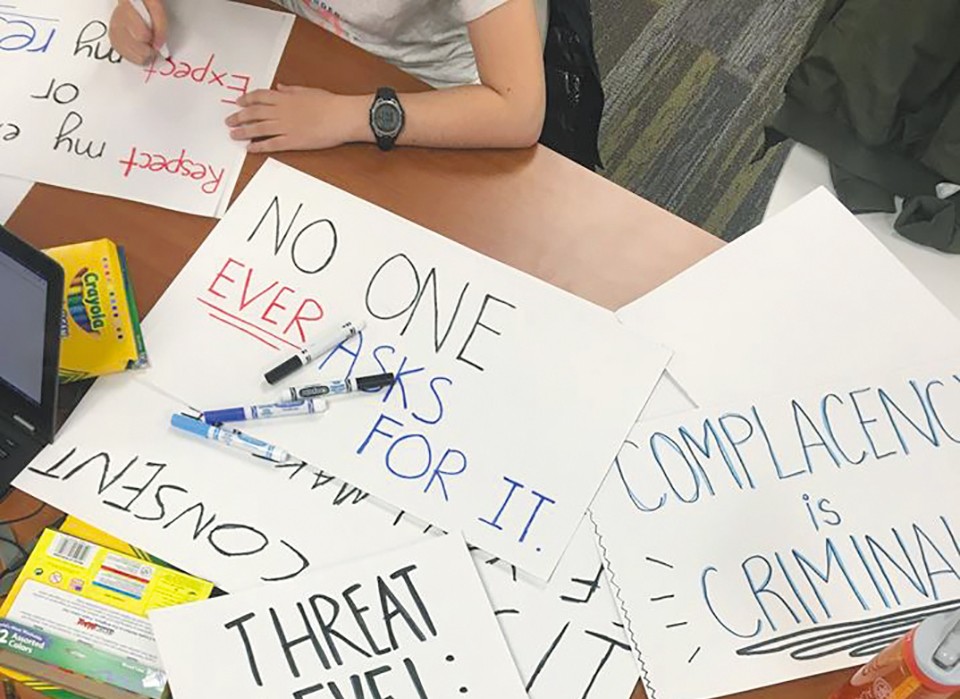

Between 9 p.m. and 5 a.m., Nat, Rachel and more than a half-dozen other students gathered to organize the movement. They transitioned from GroupMe to Slack, a website often used to streamline workplace communication.

Nat set up an anonymous profile on Slack, officially adopting the moniker "Nat," an acronym for "Not a Threat." Within the next few weeks, Nat says, as many as twenty survivors reached out to her profile seeking advice and counsel.

That night, the women committed to making the organization as inclusive as possible. They wanted to create a survivor-centered space where anyone would feel a call to action, a sense of agency and a right to claim the movement as their own.

On Wednesday evening Nat and several others held their first real public-facing meeting. One leader estimates that at least 40 individuals came to the two-hour gathering.

Luka Cai, then a sophomore international student from Singapore, is a member of Pride Alliance, a campus organization focused on LGBTQ educational, social and activism programming.

"Monday I felt really helpless when the op-ed was published. It was really the first time in my life when one issue or one article took over my mind and I couldn't stop thinking about it," Cai says. "And I was just walking around campus in this daze, in this cloud of like, something this horrible can happen on a campus where everybody just goes around doing their own thing not talking about it."

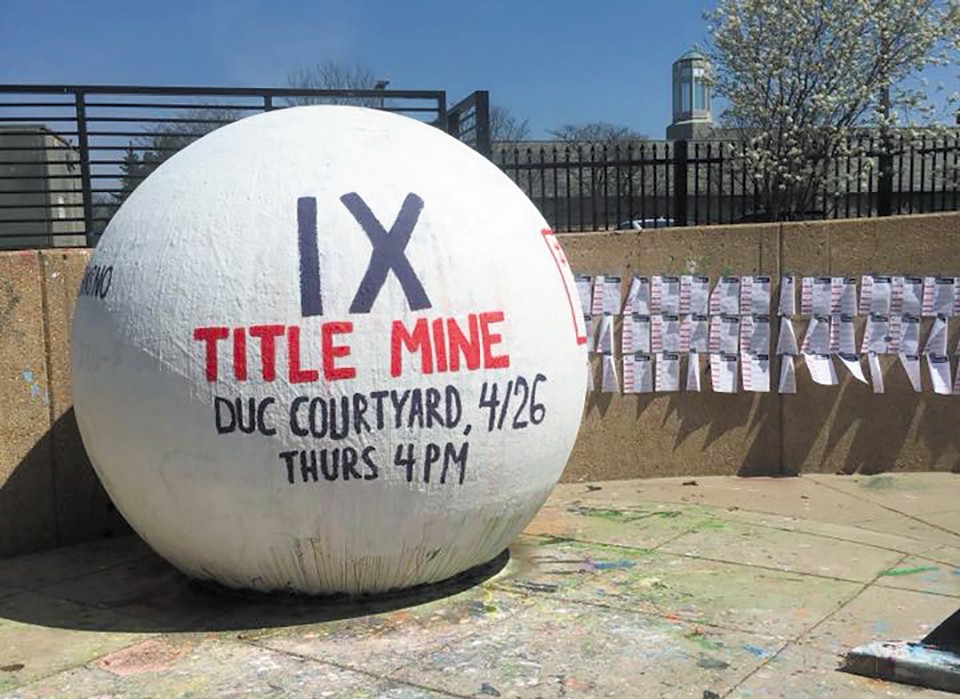

Cai found Wednesday's meeting cathartic. Attendees split into smaller groups to discuss sexual assault at Wash U. In the next few days, the group chose a name: "Title Mine," a riff on the federal Title IX laws that govern allegations of sexual assault. It scheduled an April 26 rally. And over the course of planning meetings that lasted up to six hours, the movement's leadership shifted. A new crop of organizers became involved; Cai absorbed additional responsibilities a few weeks later.

"The original leaders said, 'OK, we started this movement but we acknowledge that we don't know the most about these issues on campus and how they've been addressed. So we want to hand the reins over to people who have been fighting the fight for a longer time,'" Cai says.

Group leadership is "porous," Cai says — there are no specific roles and no set number of leaders (various members provide numbers between five and twenty).

"I think one of my favorite things about the group is how open we are," Cai says. "I feel like we're not afraid to take as long as we need to exchange diverse perspectives."

Once the basics were set, discussions about public relations began. The group created a Facebook event and a Change.org petition, which gathered 1,000 signatures within days. Members also flyered campus, including the doors of the Title IX Office.

And that was all before the second article hit.

"My decision was a no-brainer," Rachel says on publishing her piece, "Consider This a Warning."

Then a sophomore, Rachel had previously contemplated making her story public. Several survivors had come forward in Student Life's pages over the preceding years. But Nat's piece perhaps gave a final push. That week, in addition to serving as a core organizer for Title Mine, Rachel estimates she poured twenty hours into writing "Consider This a Warning." It ran on April 19.

"I was like, alright, I have to keep this fire going, I have something worth telling," she says.

In the piece, Rachel shared her personal experience after she made a sexual assault complaint against an ex-boyfriend: When the Title IX Office refused to add a clause to her no-contact order to bar him from Greek life parties she was at, she wrote, she called a meeting with the leadership of his fraternity. They told her that their international organization's policy held that they couldn't help her unless she handed over her confidential Title IX documents. When she called the fraternity's national headquarters to fact-check, the executive director was horrified, saying that even allegations could put a member on inactive status.

Rachel says her assailant manipulated and abused her for the duration of their seven-month relationship, until she broke it off in August 2017. A week later, she says, he showed up at the club she was at.

"He went to the club, he found me, and he just attacked me from behind and he started groping me and kissing my neck and he fingered me really aggressively," she remembers. The entire interaction was non-consensual, she emphasizes, and occurred as he held her tightly despite her attempts to escape. "I was bleeding, that's how aggressive it was, and a friend who was in my vicinity pulled him off of me, pulled him into the men's restroom, told him off." She says he emerged from the restroom and assaulted her again as witnesses nearby attempted to intervene and told him to back off.

In January, Rachel went to Washington University's Relationship and Sexual Violence Prevention Center and met with Director Kim Webb. Rachel opened a Title IX case on February 7.

In 2011, the U.S. Department of Education said the Title IX process should last no longer than 60 days, according to Jessica Kennedy, Wash U's Title IX office director. Yet during her first conversation with RFT in mid-July, Rachel was more than six months into her case. It was another month before her assailant was found responsible.

Wash U has never completed an investigation in 60 days, Kennedy says. In general, she says, the process lasts around six months. Last year, one case lasted nine.

A 1972 federal civil rights law promoting equal opportunity between genders in education, Title IX leaves procedures for implementation up to individual institutions — and in recent years, many universities have come under fire for failing to live up to its ideals. Students at Boston University, Harvard University and Swarthmore College are among those who have led campus rallies or protests in the past year or so.

Title IX had a national moment last September when Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos changed Obama-era guidelines to the law. She eliminated the suggestion of the 60-day investigation period and also raised the burden of proof from "preponderance of the evidence" (meaning an allegation more likely than not is true) to either "preponderance of the evidence" or "clear and convincing evidence."

At the time, Wash U released a statement reestablishing its commitment to the Obama-era guidelines.

"I think that when we look at the national climate, our students are coming with an activist and a social justice lens, and so I think this is something they can get on board with, that everyone wants to rally around survivor protections and survivor rights," Webb says.

Wash U's current Title IX process took form in 2013, Kennedy says. Under it, a Title IX report begins when a complainant makes a report alleging sexual discrimination, sexual harassment or sexual violence. If the Title IX office determines that the reported behavior would not violate the University Student Conduct Code, administrators will meet with the complainant to discuss alternative options.

If the behavior alleged may be a code violation, the respondent receives a formal notice of complaint. A contract investigator then interviews both parties and any witnesses and reviews other evidence.

A three-person panel, chosen from a pool of 110 trained university faculty, staff and students, reviews the initial report and can ask for further information, which the investigator uses to create a final report. Both parties are allowed to provide a written response. The panel reviews the report and responses, and interviews both parties and any useful witnesses. From there, it writes a decision determining whether the student more likely than not violated the judicial code. The discipline it orders can go up to expulsion.

Kennedy says students' most common qualms with the process are that it takes too long, and that those involved in the investigation may use victim-blaming or trauma uninformed-questions. And while Rachel brings up both of those concerns in her case, her issues with the process go much deeper.

"The Title IX process is a second assault," she says. "I don't think anyone would go through it if they knew better at first."

First, Rachel notes a discrepancy between the types of witnesses she and her assailant provided. Her witnesses, she says, were unbiased individuals who all happened to witness the public assault. On the other hand, the eight people who testified on her assailant's behalf were his good friends, she says. Much of that part of the report, she says, explained that her assailant is an "ROTC scholar," a "best friend" and "really respects women."

"For fifteen pages, I was slut-shamed and my personality was attacked, even though these people don't know who I am and don't know me at all, nor were they present at the incident," she says.

Many of his witnesses, Rachel alleges, were dishonest about being present.

"Easily proven-wrong lies, but the fact of the matter is that he was allowed to lie and he did it and he did it everywhere in his case," she says. "I wondered, why is this even worth it? Like the only bit of truth you'll see is gonna be from the survivor, because there's nothing in it for us. There's literally nothing in it. And for him, on the other hand, he has an ROTC scholarship [to protect]."

In part because he had provided many witnesses, the initial investigative process didn't end until April 24. As it trudged forward, Rachel feared for her safety. She and her alleged assailant were enrolled in two of the same courses.

"I actually failed my first exam in one of those. I had prepared, I tried to feel good about myself that day," she remembers. "And I just went in and just like every other day, he just stared me down, stared into the back of my head. It was intimidating and not OK. And I felt very threatened."

The Title IX Office's initial solution, Rachel says, was a modified seating arrangement. After hours of meeting with the dean, her assailant was eventually moved to a different class. (Once he was out of her class, she says, she began earning near-perfect scores again.)

Still, his new class was directly after hers, and he would make a point of sitting outside the classroom, she says. For the first time in her life, Rachel began experiencing panic attacks.

Rachel moved to an off-campus apartment to reduce potential contact. But when she told the Title IX Office she wanted to ensure he wasn't allowed at parties she was at, she says, she was told it was not possible.

That became the subject of her op-ed.

"They will keep you safe in the classroom, but it's stupid, because it's not like I'm going to get assaulted in the classroom," she says. "I'm going to get assaulted in a dark room with alcohol where the risk is higher."

That wasn't Rachel's only frustration. In one instance, Rachel says the Title IX office tried to give her assailant access to her health records, including psychiatric history, medications and birth control information. She says she wasn't clearly told that by sharing them with investigators, her assailant could see them too, and she had to fight to pull them back after learning he'd have access to them.

"[The Title IX Office] will release your private and protected health records without your consent to your assailant and without your knowledge, which is horrific," she says. (Kennedy emphatically denies this: "Washington University does not, under any circumstance, provide access to or share an individual's personal health records of any kind without the consent of the individual.")

And Rachel balks at the idea that the burden of proof falls on the survivor. Even after she won her case, she wonders how anyone ever does. She felt it was hard to provide the evidence the panel wanted because she didn't send a text or give a friend a play-by-play right after it occurred.

"It takes a while to open up about assault, not necessarily saying that you were assaulted. I was able to say that within the first day, within the first week, I was telling people I was assaulted," she says. "But it takes much longer to say, and be comfortable with saying, 'His fingers were in my vagina, they were scraping me, he was aggressive and I bled.' That was something that took me a long time to be able to say."

Once she finally made it to the panel interview, she grew even more frustrated.

"They just asked me really intrusive, borderline victim-blaming questions," she remembers. "The first thing they asked me too was physically how he assaulted me, and I was just floored, because they already have an audio recording of it from my interview with the investigator, they have seen me write it out in three different forms and they wanted me to say it again."

In "Not a Threat," Nat described her concerns about the lack of communication between the many offices tasked with ensuring student safety on campus.

Her nightmare began in February of her junior year. Her friend's ex-boyfriend, someone she'd considered a friend, drank too much at a bar. When she tried to take take his drink, he grabbed her hand and twisted her wrist until it was sprained. Later that night, he refused to leave her apartment until she dialed the police. Still, they fell in and out of contact, and in October, she says he sat on her at a party, choking her until she passed out.

She reached out to his residential advisor, who she believes reported his dangerous behavior to a superior, but Nat never heard anything about it again. In February, Nat's friend, his ex, overheard him plotting her own murder.

The Washington University Police Department was summoned. Over the next few days, Nat says that she and several other individuals went to the Title IX Office. Nat also gave a statement to the campus police.

The Title IX Office informed her that her case constituted physical, not sexual, assault. Both Title IX and the campus police indicated the case was a more appropriate fit for the Office of Student Conduct. A week or so later, she says, she received a phone call saying that Student Health Services had evaluated him and deemed him "not a threat." She says the campus police told her that her file had been passed along to Student Conduct.

Nat says she called Student Conduct several times over the next few months, but never heard back. This April, she learned that an underclasswoman had accused the same man of rape. That was when she decided to go to the Student Conduct office. Yet when she inquired about the status of her case there, she says they'd never heard about it.

"It was a major failure in communication," she says.

Exasperated at this disjointedness, distrustful of the offices she had sought out for support and wanting immediate answers, Nat began writing her article that night, April 10.

"The day that article came out, I got a notification that he had been removed from campus," she says. "The day that article came out. Not a day before. Not when I went into the Office of Student Conduct. That day."

But the movement she'd unexpectedly launched didn't stop with Nat's case. In the coming weeks, other students' personal essays flooded Student Life's editors' inboxes.

"We knew that there was still work to be done and we regularly assess the process, assess how our investigations are going, we seek feedback, so that was some very pointed feedback we received in those op-eds," Kennedy says of the outpouring.

The essays were harrowing.

The day after Nat's piece was published, Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs Lori White wrote about her own sexual assault in "My Heart Sank ... Because I Understand." "On Staying Quiet" was about a girl who wondered if she'd been drugged before her assault at a fraternity from which she was later blacklisted. "Survivors Are Students Too" tackled systemic difficulties students faced after assault on campus. Then, the day of the rally, "Three Weeks Later" debuted, written by a freshman who alleged that Nat's assailant had raped her.

"While I only found out about his history afterwards, Washington University had multiple reports about this student and was aware of his violent tendencies long before my assault," the young woman wrote. "He was the subject of the Student Life article 'Not a Threat,' and I am the freshman that he raped. Washington University failed. They failed to protect its students, and my rape is a direct consequence. If they had taken action earlier, this would not have happened to me."

Part of the problem, Nat believes, is that everyone knows the Title IX Office is ineffective. If survivors know how difficult and frustrating the reporting process is, why would they bother to make a report?

In the 2015 Association of American Universities Campus Climate survey, 22.6 percent of Wash U's female undergrad respondents said they'd been subject to some form of nonconsensual sexual contact. Between 2014 and 2016, 62 reports of rape were made to the Washington University Police Department. Yet in the 2014 to 2015 school year, only five Wash U students opened Title IX investigations. In those cases, three respondents were found responsible.

In 2016-17, that number jumped to thirteen, with six found responsible (one case was withdrawn by the complainant).

Hannah*, the author of a May 1 op-ed, "Victim of the Gray Area," chose not to report her incident. The junior says she had never previously met anyone via Tinder, but in January, decided to meet up with a fellow Wash U student she'd swiped on the app. The first date, she recalls, was enjoyable. The two watched a movie and kissed. Eventually, the relationship progressed into a sexual one. The two decided to keep it at the "friends with benefits" level.

One night, after going to a party, Hannah went to her Tinder connection's fraternity. All she remembers is talking, with clothes on. Yet she woke up naked next to him that next morning. She rushed to class, but that night, she stayed in and cried.

Hannah believes there was a lot of "gray area" in her case; they had had sex and been on dates previously, and she was drunk. Plus, she points out that hookups are almost "expected" at fraternity parties. Had she consented that night? She wasn't sure if what happened was "real assault."

"It took me a little bit to realize that I was uncomfortable with what happened," she says. It was only after a friend told her the situation was not OK that she began to process it. "It was only after she said it to me, I realized, 'I don't feel comfortable.'"

Hannah contacted the boy two days later, and he walked her through his recollection of the night. He wasn't sure why she was uncomfortable — they'd had sex before.

"He said that I was apparently too drunk to walk home so that's why he had me stay there, but according to him, I was saying that I wouldn't stay unless we had sex," Hannah says.

Just as Nat fears, Hannah felt deterred by the Title IX reporting system. Hannah remembered reading in Student Life about a freshman who reported assault right as winter break began. In the piece, published in May 2017, a freshman wrote that the director of the Title IX office suggested they delay the reporting process until spring so that her rapist could "enjoy his winter break."

"That story stayed with me," Hannah recalls. "I was like, 'If they didn't take that seriously, why would mine be taken seriously?'"

Even if she wanted to report, Hannah says, she wouldn't know how. At the time of her assault, Hannah was seeing a university counselor for unrelated issues. When she mentioned the incident, she says, the counselor said she didn't know much about the process and would have to look into it. She told her counselor not to bother; the therapist didn't press further.

Of her Tinder boy, Hannah says today, "I just don't know if he did this maliciously or not, so I don't know if I want to classify it as sexual assault, even though I know the definition of it doesn't need to have any sort of intent on his part. But I still kind of struggle with that."

When the op-eds began pouring in, Hannah saw an opportunity for closure.

"I felt guilty about not reporting it because of how many people experience sexual assault on campus. And me not reporting means another case that goes uninvestigated, another one slips through the cracks and gets away with it and doesn't have repercussions," she says. "So I felt like this was my way of doing something I was comfortable with, where I'd be able to remain anonymous but still put it out there and let it be known to the community that this happened."

In her piece, "A System Where You Can't Win," junior Maddy Yaggi chose to use her real name. She was tired of hiding. Published May 3, the op-ed divulged her experience living on campus just after her rapist was expelled.

Yaggi says she was raped after a Super Bowl party during her freshman year, by someone she had been casually dating. She woke up the next morning, confused and bleeding from both her vagina and her anus.

After later talking it through with friends, she says, she concluded that she was either unconscious, asleep or blackout drunk during the assault. "I'm still not positive which of the three it was," she says. She had memories of her head hitting against things (the wall, a shelf, a dresser). "When my head hit, I would snap back into it for a second and I would have a couple seconds [awareness] of what was happening," she says. "And then I would be blackout or asleep or too drunk again and then not come to until my head hit against something else."

Yaggi wasn't sure what to make of the incident until others explained it could be rape. After a semester of trying to cope — running for miles on end, drinking and partying more than she ever had, avoiding romantic and sexual relationships — she contacted the university's Relationship and Sexual Violence Prevention Center and got a no-contact order. When she returned to school in the fall, she decided to report.

It was a nightmare, she recalls. In one instance, after she and her assailant provided their responses, she received no warning other than an email saying the responses would be available for viewing in 30 minutes. Yaggi had no time to get into the right headspace. Although she had a biology exam just an hour later, she read the response anyway. She had to know what it said.

"There was really no regard for how traumatic the reporting process actually is," she says. "That really solidified it for me. I bombed that test. I couldn't focus at all."

Another exam fell a day or two away from the release of the final panel decision. She asked for an accommodation, but her professor refused. Ultimately, he gave Yaggi a zero on the final. She now has to retake the course.

The crux of Yaggi's piece, however, is what happened after all that. When her rapist was finally expelled, he had two weeks to file an appeal. He waited until the last minute, granting him another two weeks on campus. Because he had received the highest punishment, expulsion, Kennedy told her the university could not punish him further for any actions he committed during the appeal period.

During that month, Yaggi wrote in her op-ed, she feared he would retaliate. When she expressed this worry to the Title IX Office, she wrote, she was told that if she felt unsafe, she should call the campus police. The offer simply felt like the function of the police: You feel unsafe, you call them.

In reality, he was living off campus that entire terrifying month, but Yaggi was never informed. The Office of Residential Life was aware he had moved out, but the Title IX Office wasn't, Yaggi wrote. She saw it as evidence of poor communication between different university offices.

Yaggi's op-ed came at the end of the wave, after the rally.

"I was just so inspired by everyone else who was coming forward and saying their stories and what they went through, but what I thought was missing from that was that even if they made the changes they were advocating for, there are still fundamental problems with the system," she says. "So a lot of what I saw calls to action for were 'We need to fire Jessica Kennedy' or 'we need to get more cases reported or settled in favor of the survivor,' which seem to me like simple answers that wouldn't get at the root of the problem. So I wanted to tell what happened to me even after I won my case, even after he was expelled. It's not one person's fault or a statistical issue. They need to fundamentally rethink this whole thing."

At 3:45 p.m. on April 26, ten days after the publication of "Not a Threat," cries of "WHOSE SCHOOL? OUR SCHOOL" broke out in the student-center courtyard.

"The first thing I noticed was the sheer number of people at the rally, including faculty members and administrators," Cai says.

Organizers distributed flyers with chants on them as well as a final list of demands. One leader read a short statement by Nat, who'd chosen to maintain her anonymity. She was among the crowd that day.

"I didn't feel the need to take up space at the rally when there were more than enough other voices to fill in," she says. "So I just wrote a little bit of an introduction, because I thought it would be weird if I didn't have any presence."

Organizers then turned over the mic. Student after student after professor stood up to share their experiences. Others submitted anonymously through a Google form and had their stories read by Title Mine members. The rally continued for more than two hours.

Cai broke down in tears at its conclusion, overwhelmed by the outpouring of emotion. For Rachel, the rally was an opportunity to deliver an impassioned address. For Yaggi, the rally was a final push to write her story down. And for Hannah, still struggling to determine if she had experienced a "real assault," the rally provided something she'd been searching for all along. She realized, she says, that even if she can understand the gray areas, "I am still validated in feeling like something happened that was wrong. And at the end of the day he did do something wrong and it wasn't my fault. It was really emotional."

Chancellor Mark Wrighton, Webb and Kennedy were among the administrators present.

"It was very hard to listen to the students talk about their experiences and how it has affected them in negative ways, and not just their experiences here, but their experiences growing up," Kennedy says. "But I was really glad they had the forum in which to say what they did."

The next day, the entire student body received an email from Wrighton.

"It was a heart-wrenching two hours. Hearing the personal stories and knowing that we have fallen short in effectively supporting victims of life-shattering sexual assaults is very difficult," he wrote in the email. "I am deeply troubled that even one of our students would be assaulted by another student. It was extremely important to me to hear firsthand from you, and I appreciated the opportunity to be present."

Wrighton made four commitments to be acted upon by the start of the fall semester: develop a plan to streamline the Title IX process, invest more in survivor resources and mental health services, create a peer-advocacy program to assist those going through the Title IX process and create accountability measures. White, he wrote, would supervise this work.

The week after the rally, six Title Mine organizers sat down with White and Webb.

"You hear such amazing things about both women on campus, but just getting to sit down with both of them and have what I felt was a very open dialogue where I was able to feel comfortable specifically speaking to how students on our campus deserve to be better accommodated," says Candace Hayes, one of the student organizers.

Cai says that White seemed open to the suggestions the organizers made. Hayes recalls White taking detailed notes.

"We were all a little bit apprehensive and we didn't really know what to expect because we had been taking this antagonistic destructive stance against the administration, but they were extending good will toward us," Cai says. "So on one hand, I felt like we wanted to grab the opportunity and be able to work with the administration, but we didn't want to betray the original destructive angry message the movement was meant to send."

In the fall 2017 semester, university administrators had co-hosted three Title IX listening sessions. The administrators say they found them helpful in understanding students' perspective.

"I think one of the other things we discovered in the listening sessions is, we have to think about better ways to help students understand the process," White says. Often, she says, it's not until students file a report that they learn about the process. "And in the midst of a traumatic experience, that's really overwhelming."

Today, both the student organizers and the administrators emphasize the importance of collaboration.

In addition to working with the administration on its five core demands, Title Mine has worked to keep the momentum going. They hope to make better training mandatory for student groups that host large social events. They are negotiating a relationship with local nonprofit Safe Connections to ensure training and therapy. They also plan to provide a platform where students can select training options that fit their organization's needs.

Perhaps the most visual manifestation of the group's continuing efforts was its Red Tape Initiative. As commencement approached, Title Mine set up shop outside the bookstore where seniors pick up their caps and gowns. There, members distributed strips of red tape for seniors to place on their graduation caps, either as a strip or in the shape of "IX."

The idea, says Cai, was to let graduates "show their solidarity with survivors of sexual assault."

Cai adds, "And we thought it was particularly important to show the privilege that certain perpetrators at Wash U have been given by being allowed to graduate and the burden being placed upon survivors to have to graduate with their perpetrators and see their perpetrators at graduation and commencement."

As her case is still pending, Nat cannot say whether her assailant was among the sea of green-and-black robes May 20. What she does say, with slow, careful words and a tight voice, is this: "If there is a case currently pending against someone, they don't graduate."

At her academic division recognition ceremony, Nat displayed red tape. But when it came time for the university-wide commencement ceremony, she was running late. Plus, it was raining. She never put on her tape. And so, in her commencement photos, Nat looks like any other student: no red tape. And in a lot of ways, she feels like one too.

"As life-encompassing as this was, the big part of the story is the last three weeks of my senior year..." she says. "But I don't think it was by any means a bad four years. I have made some of the best friends that I have ever had. I have had some of the greatest memories ever."

And when it was time to move out of that sterile temporary dorm, she threw away the newspapers she'd painstakingly collected.

"I felt like I needed to move to different things," Nat says. "I said, 'OK, I had this space and I focused on this. And this was like my project, this was my life while I was here.' But I still have a life outside of this. And I need to be part of that."

Alison Gold is a junior at Washington University studying psychology, writing and design. She is the director of online content at Student Life. This summer, she interned at Riverfront Times.

** Names of some students have been changed to protect their anonymity.

Editor's note: The version of this story published in print contains a mistake due to an editing error. Nat's friend overheard her ex plotting her own murder, not the murder of Nat. We regret the error.