The Lawyer

Vonne Karraker had not planned to become the leader of the local resistance. In 2003, after law school and some work in the insurance industry, she followed her husband to Farmington, the seat of St. Francois County. The marriage didn't last, but she fell in love with the town of 14,000 in the former lead-mining region south of St. Louis. A municipal official who threatened to prosecute her for not returning a library book became her second husband, and they started a small law firm that catered to elderly clients, listing their dog and two sugar gliders (tiny marsupials) as members of the staff.

St. Francois County was 96 percent white, and Karraker — who grew up in Missouri's southeast Bootheel — was almost always the only Black person in the room. This wasn't new for her. As a child, she had been bullied at a mostly white school, only to go home and have her siblings accuse her of trying to act white. As an adult, she found being an outsider gave her a knack for seeing beyond appearances, into the casual ways people exercise power. "I can hear David Attenborough narrating the way people behave around me," she told me. She liked letting the liberals think she was conservative and vice versa. "I describe my politics as the golden rule."

Every community has drama, but St. Francois County seems to have more than its share. Not so long ago, a local KKK leader was murdered by his cat-hoarding wife, and a city councilman was accused of punching a woman in the face at a bar. In 2016, the local grapevine was dominated by the saga of Kristy Cunningham. She claimed in a lawsuit that her husband had an affair with a woman who went on to conspire with local leaders to throw Cunningham in jail on stalking charges. Her small daycare business crumpled, and she was separated from three young children. After three months, she pled guilty just to go home.

The defendants denied her allegations and the lawsuit was dismissed, but Karraker found this tale of power abused believable. A few years before, she'd been asked to meet with a woman who claimed to have witnessed the elected top prosecutor, Jerrod Mahurin, hand out illegal raises to favored employees. At the time, she'd declined to get involved, but now, seeing what happened to Cunningham, she felt guilty for not doing more. So when another woman came to her with sexual harassment claims against Mahurin, Karraker became her confidante. They once met secretly in a cemetery. "She'd shake, smoke cigarettes," Karraker recalled.

The Riverfront Times and St. Louis Post-Dispatch covered the allegations against Mahurin — which he denied — and while Karraker's name was seldom in these stories, many in town knew she was behind the scenes. During a radio interview, Mahurin named Karraker and said, "I will certainly have my day to go after these people." (Her husband Kevan Karraker wrote an open letter in response: "Why wait?") Mahurin, who was not charged with any crimes but faces ongoing lawsuits, was voted out in November 2018.

"Vonne is like many people in these situations, who sound like a conspiracy theorist at first, and maybe she is a little bit, but the stories are just that bad," said Post-Dispatch columnist Tony Messenger, who won a Pulitzer Prize for a series that included a piece on the St. Francois County justice system. "She has the whole weight of the town on her at times."

Karraker kept paper and pen in hand, in case someone buttonholed her with some local government woe. "People would come in, tell me outrageous shit, and I would either prove or disprove," she said. "If I could prove it, I'd write about it on Facebook." At one public meeting, as she demanded financial records from an official accused of overcharging the county for road inspections, a commissioner threatened to have her escorted out and summoned two deputies.

By the time Joe Braun approached her about his stepson's death, she was exhausted and ready to step back, but she'd been hearing for years about the jail. She'd met Natalie DePriest, a local activist who had gained national attention after she and her brother were sentenced to fifteen years in prison for growing marijuana plants in their home. DePriest told Karraker that when they first went to the jail, in 2011, she demanded a lawyer and said to a jailer, "I have constitutional rights, you're not my king," and that he wrapped his arm around her neck and struck her as he dragged her toward a cell, where a second officer pepper sprayed her. Her brother, David DePriest, saw all of this while waiting in the booking area. "For hours, I had to sit and listen to my sister scream, asking for a nurse, for clothes, since hers were soaked in mace," he told me.

In a use-of-force report, officers wrote that DePriest "stepped in an aggressive manner" and moved her hands towards one of their faces, but was "contained with no injury to staff or inmate." DePriest had photos of bruises, taken several days later.

Karraker interviewed inmates who had heard Billy Ames's screams and filed a wrongful death lawsuit in February 2019. Once the lawsuit got media coverage, posts to the local Facebook groups swelled with stories about the jail. A resident showed me a meme calling the jail "Missouri's New Death Row." Karraker was contacted by family members and friends of two people who had died by suicide in the jail within a few months of Ames's death. One was Michael Bennett, who repeatedly told officers that he was suicidal and yet was placed in a cell with few precautions.

Sheriff Bullock had requested state investigations after the deaths of Ames and Bennett, as well as, years earlier, after deputies were accused of sexually assaulting detainees. (One deputy committed suicide in 2013 while facing indictment for a sexual assault.) But the sheriff didn't always ask for them. Karraker also met Jeffrey Tupper, a former state employee whose wife Tabitha had died inside the jail in October 2017, after being arrested for violating her probation, which stemmed from her opioid addiction. During visits, Tupper had noticed she was losing weight and looked unwashed. "I took our kids to visit her and she was in a torn-up gown," he said. "She had to hold it together." She complained of headaches, and her autopsy cited a brain abscess, but because her husband never received word of any investigation, her death remained shrouded in mystery, and Karraker would have to start from scratch.

Karraker was contacted by at least four current and former sheriff's deputies. One told her that Dennis Smith "overrules and covers up everything" and "is pretty vindictive." (Another told me Smith, a liberal Democrat, had tried to improve the jail when he was hired in 2003, but "gave in to peer pressure" after deputies called him "hug-a-thug.") Karraker had once been friends with Smith, attending parties at his house and even taking a tour of the jail with him years earlier.

"Just because someone is nice to you, doesn't mean they are a good person," she said.

In her email inbox, Karraker received pictures of a young man's stomach and hip, covered in a massive infection. He had told his family it came from a spider bite in the jail. At one point, hearing a vivid description of a sexual assault inside the jail, Karraker said she vomited. "If I slow down to think of the sheer magnitude of the evil that resides here I cower at home under the covers, exhausted and weepy and thoroughly overwhelmed," she wrote to me in an email. "That's happened a few times, and [my husband] has dragged me back into the light."

Many of the stories were likely unprovable but gained credibility through sheer repetition. For instance, Karraker kept hearing three words over and over again: "Friday Night Fights."

The Detainees

In a small town, the jailers and the jailed often have history. John Rastorfer, who has been in and out on various charges, said he heard jailers say to incoming detainees, "Hey, remember me? You used to pick on me," and "You fucked over my sister," and then the jailer would "treat them like shit." Several men who spent time inside described a dynamic in which jailers who had been bullied in high school took revenge.

Many told stories of seeing people ignored by jailers while detoxing. St. Francois County sits at the center of two American drug epidemics, having had among the highest rates of opioid prescriptions and methamphetamine lab busts in a state known for both. Farmington is relatively affluent, but in other parts of the county, more than a quarter of residents live below the poverty line. A coronavirus outbreak can literally spread from a jail to the surrounding community, but former detainees described how this jail has long exported less traceable problems, like addiction, violence and trauma. "It's putting the youth of this county through a grinder," said former detainee Joel Burgess, "and it's for nothing."

They told stories of seeing jailers beat and mace detainees, and of being beaten and maced themselves. They described staph infections and scalding shower water that they let cool in a trashcan before bathing. A former deputy who declined to be named said it was well known that the phrase "take him to the shower" was code for assault, as the shower did not have cameras, and complaints to superiors would fall "on deaf ears." Ten women, and one former employee, said jailers would withhold sanitary products and then throw them into living areas, to spark a violent scramble. "We had bitches back there bleeding in oranges," said Stefani Rudigier, referring to jail uniforms.

At times, the sheriff made light of the grim conditions. During a period of overcrowding in 2013, he followed the example of Joe Arpaio, the famously punitive Arizona sheriff, and housed people in tents. "We jokingly say around the county, 'That is the Daniel Bullock's Bed and Breakfast,'" the sheriff told a reporter. (He told me he did not consider Arpaio's policies a model.) The county held a contract with the U.S. Marshals Service to house federal detainees, but this stopped in 2017 after an inspection found inadequate nutrition, water leaks, ants and a lack of natural light because cell windows had been covered in black paint. (The inspection was obtained by reporter Seth Freed Wessler, who wrote about such contracts for Mother Jones and Type Investigations last year after suing the Marshals for access.) Bullock told the local newspaper, "I'm not running a Hilton Hotel here."

Even county residents who had never been to the jail traded stories about "Friday Night Fights," which according to more than a dozen former inmates involved ritualized, two-man duels, often to prepare men for state prison. "On many occasions I could see the outlines of officers standing outside the tinted glass, looking into the pod," recalled Maxwell Lee, who was in the jail in 2014 and 2015 facing charges of killing two people during a robbery.

The jail has developed its own lingo, with particular areas dubbed the "Thunderdome," and a group of especially violent men called the "wolf pack." Five people said jailers would announce which inmates had been charged with sexual crimes against children or were informants to police, knowing they'd be victimized. "The predatory clique ran the pod," wrote James Gannaway from prison, where he is serving time for a domestic violence conviction. "Every three days or so a batch of hooch would come in and the clique would go insane."

Among former St. Francois inmates who have moved on to state prison, mention of the jail evokes knowing looks and war stories. Missouri prisoner Bobby Bartlett said his cellmate appeared ravaged by post-traumatic stress after time in the jail, and when Bartlett, who is not from the county, asked others to speak with me, many refused. "My family goes in and out of that jail all the time," one told him. "They will kill them just to get back at me for talking."

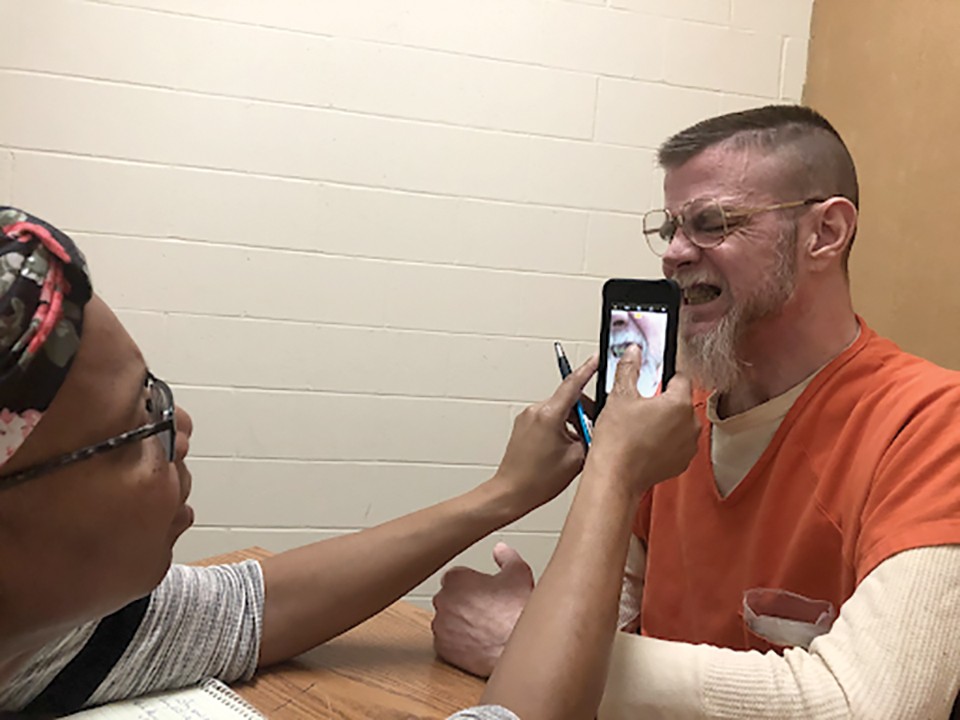

Still, as word of Vonne Karraker's work spread, more and more people who had been inside posted stories on Facebook. She entered the jail herself to visit Clinton Wheeler, who complained he'd been denied medications and doctor visits. (At least six other people have alleged medical neglect in lawsuits since 2004.) Karraker shot a video of what she thought was dried blood on the floor. Wheeler, who was facing murder charges for shooting his son-in-law, was nearly skeletal, with black spots on his teeth and gums.

As they spoke, she heard a "massive, 3-D cough." Convinced someone was listening, she abruptly ended the conversation. She later learned that a local lawyer was contacted by jail administrator Dennis Smith, in an attempt to stop her from meeting with the lawyer's client.

Karraker lives far from a major road, and she and her husband Kevan both began noticing mysterious cars at the end of her driveway. "As I walk towards them, they leave," she said. "All I can say is: white dude with dark mustache." (Joe Braun also claims Sheriff Bullock followed him around in his car. The sheriff denies this.) Karraker started to feel afraid when she stayed late at the office. Whenever she prepared to enter the jail, she'd text numerous friends, telling them if they didn't hear from her in a specified number of hours to "raise hell."

I witnessed Karraker do this before we went to meet one of her clients inside. When we left safely, she forgot to tell her friends, and they began to panic; her husband was not pleased.