Autumn, 1975: Bob Dylan, having recently returned to live performances after years of laying low, his every move scrutinized for signs of which way the times were a-changin', began a tour of smaller venues along the northeastern U.S. and Canada.

The Rolling Thunder Revue was, as its name suggests, far from a typical rock concert. In addition to performances where he shared the stage with Joan Baez, Roger McGuinn, Ramblin' Jack Elliott, Allen Ginsberg and a gypsy-like band, Dylan had fashioned the tour as a kind of caravan, paying pilgrimages to historic sites like Jack Kerouac's grave and making unannounced appearances in small-town banquet rooms. To add to the chaos, he brought along a film crew and invited playwright Sam Shepard to help him stage semi-improvised scenes in which Dylan, his wife Sara, Baez and a few guest stars play-acted a psychodrama based on his married life. The result all of this was four hours of uneven but occasionally illuminating observations on music, love and the larger-than-life Dylan persona. Titled Renaldo and Clara, it was released in 1978 but has rarely been seen since (except in bootlegs).

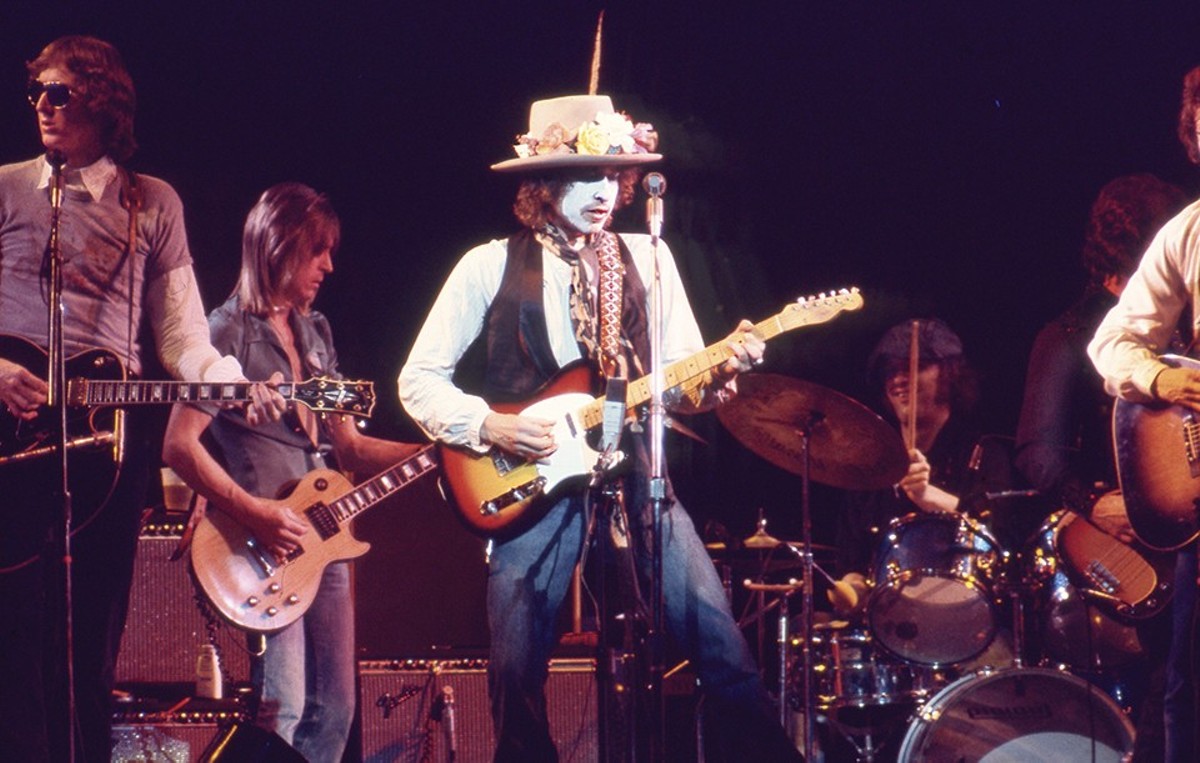

The Rolling Thunder tour was, in a sense, Dylan's go-for-broke effort to exploit/expose the public image known as "Bob Dylan." On the advice of theater director Jacques Levy (who co-wrote most of the songs on the Desire album), Dylan was creating a more theatrical version of himself for the concert stage, with broad, exaggerated gestures and using makeup and masks.

Forty-four years later, Dylan called on Martin Scorsese to help relive that 1975 tour — or remake Renaldo and Clara. Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin Scorsese is a freewheeling film that restores the best concert footage while embracing the masks-and-illusions concept of the entire venture. Scorsese previously worked with Dylan on the excellent 2005 documentary No Direction Home, a skillfully edited account of the songwriter's early career. But if that film was a collaboration, this one is more of a conspiracy.

Scorsese embraces the Rolling Thunder concept to construct a fantasy recreation of the 1975 tour, complete with its role playing, rumor spreading and outright trickery. It's more of a cinematic magic act than a documentary, announcing its intentions with a nod to French illusionist Georges Méliès, and Dylan's ambiguous statement (call it a confession) that "when someone's wearing a mask, he's gonna tell you the truth."

Any project connected to Dylan is inevitably subject to intense scrutiny; not content to simply follow his music (or books or occasional film), the Dylanologists look for secret motives, always asking "What's Bob thinking now?" Overruling his subject's objections ("I don't remember a thing about Rolling Thunder," Dylan argues. "It happened so long ago I wasn't even born"), Scorsese tries to get inside his mind by building the film around the recollections of those who crossed Dylan's path. The filmmaker who shot the concert scenes; the promoter who struggled with the flow of money; Baez, who shed her usual demure manner to shake it on stage with the band; and even a few figures whose roles in Dylan history have largely been ignored. That may or may not include actress and fellow KISS fan Sharon Stone and former presidential candidate Jack Tanner, best known for the HBO documentary about his failed '88 campaign; Scorsese is certainly having fun.

Although most of the participants interviewed so many years down the road look at their Rolling Thunder experience as a great transformative adventure, the tour is often dismissed as a chaotic mess, unruly and uncoordinated. (Sam Shepard wrote that the event wasn't formless but had simply taken on a form that no one knew how to keep up with.) Scorsese catches both views — chaos and bliss — but shows how they came together at the tour's end when Dylan decided to apply his energy to the case of Rubin "Hurricane" Carter, the former boxer who had been framed for murder. Dylan's song "Hurricane" is a small masterpiece, a novel in ten verses, and the film shows an unusually motivated Dylan pushing his record label to release it, gathering his band for a benefit concert (as well as a performance at Carter's prison) and finally, delivering a blistering, angry performance, which essentially serves as the film's climax. He's still in makeup, still playing the role of "Bob Dylan," but he's on fire, telling Carter's story with anger and with eloquence.

The film suggests this is what the whole crazy caravan is about: the minstrel shouting his message to the world. The masks are off, the impish streak that pervades the film is put aside and we get to see Dylan at his best, as a minstrel/prophet/poet shouting down the world's injustice. He may bristle at the role, but Scorsese's crazy, brilliant film reminds us that there's no one who can do it better.