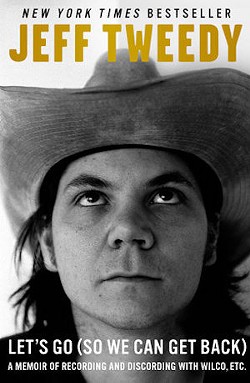

In Let’s Go So We Can Get Back, Jeff Tweedy has written a courageous, insightful memoir of growing up an indie rocker in the Midwest and on the road with Uncle Tupelo, grinding his way steadily to rock stardom with Wilco. Tweedy is now firmly associated with Chicago, but he grew up in Belleville and made his first name as a musician in Cicero’s Basement Bar in the University City Loop, and those origins mark his memoir as surely as his life.

Tweedy shows courage in writing in plain, raw terms about his battle with behavioral disorders and addiction. If his trajectory as a musician appears enviable — making a living making music on his own terms with fabulously talented musicians, winning Grammy awards, producing records for Mavis Staples and Richard Thompson — it’s impossible to want to be inside his head once his full story is known. The book is a rare rock star memoir where the hero repeatedly ends up weeping on the floor in public or sleeping beside a toilet after hours of vomiting from anxiety.

Tweedy narrated his struggle with anxiety and depression on the Hilarious World of Depression podcast in November 2017 and tells the same stories, often in the same terms, on the page here. It’s a harrowing and, ultimately, redemptive story. After finally seeking institutionalization for dual treatment of depression and addiction, Tweedy was released to a halfway house, where a fellow resident came upon him playing guitar — which he had not done in months — and encouraged him to keep it up. Already a veteran, at that point, of obsessive fandom, Tweedy genuinely was redeemed to be encouraged by a stranger with no knowledge of his musical career — a person who simply urged him to just be a little more confident.

That’s the opposite conclusion that Jay Farrar reached after sharing a stage (and an uninhabitable apartment and rancid vans) with Tweedy in Uncle Tupelo. We learn that Farrar quit the band of their youth on the verge of stardom because he thought Tweedy was too infatuated with himself. Tweedy is courageous in writing about his splits with both of the Jays in his musical life, Farrar and the late Jay Bennett, not least because Farrar all but dodged the subject in his own 2013 memoir, Falling Cars and Junkyard Dogs. Farrar could not even bring himself to commit Tweedy’s name to the page, simply referring to him as “the bassist” — which itself speaks volumes, since when Farrar broke up Uncle Tupelo, Tweedy clearly was emerging as a co-leader, something Farrar still finds hard to swallow.

Tweedy, on the other hand, writes with great insight about their partnership, even admitting that in Wilco's early days he was still writing as if to complement Farrar’s songs — a surprising, humble admission. Tweedy emerges as an insightful critic of his old band, saying that Farrar’s voice makes everything he sings “sound like the Old Testament.”

Tweedy’s take on his relationship with Bennett, which can be seen unraveling in Sam Jones’ 2002 Wilco documentary I Am Trying to Break Your Heart, sits less well because Bennett is dead and the other members of Wilco, who might offer alternate perspectives, are essentially Tweedy’s employees and not quoted. (If this book makes you not want to be in Tweedy’s head, it doesn’t exactly make you want to be in his current band, either.)

Tweedy is, again, courageous to face head-on the claim made by many that Wilco without Bennett has been a lesser band — in my view, much less dynamic and especially much less melodic. “I Can’t Stand It” from 1999's Summerteeth — which has Bennett all over it — has more hummable melodies in one song than entire Wilco records that came after it. Without knowing it, Tweedy accounts for the decline in melody and dynamism in his songwriting when he describes his current process of writing alone with no intended audience other than himself. His own recorded output shows he writes much better in more active interplay with other musicians.

Tweedy later writes with great joy about what sounds like a more dynamic musical environment than Wilco in his jams and collaborations with his sons, Spencer and Sammy. Tweedy’s book does make it sound like his family would be a happy place to find yourself, if inside his head and main band might not be. That is, if it weren’t for the cancer.

Tweedy writes about going through cancer (twice) with his wife, the former Susan Miller, former owner of the legendary Lounge Axe in Chicago. Tweedy uses the effective tactic of transcribing interviews with his wife and Spencer to get their voices and perspectives on him and their family into the story. If there is anything more dangerous about writing about one’s own intact rock band, that would be writing about one’s own intact family.

Knowing Tweedy a bit — having come up in the same music scene with him, played gigs with him, bought a band van (lovingly described in the memoir) from him, and booked a tour around an Uncle Tupelo session so one of my bandmates could play on the band's 1991 record Still Feel Gone — I see one major missing interview here. I can’t believe he never sat down and spoke to his manager, Tony Margherita, about how to handle sensitive band issues, as he interviewed his family members about their family. After his immediate family, his decades-long partnership with Margherita must count as the most crucial relationship in his life, but it goes unexplored and almost unmentioned.

I know, because Margherita told me at the time, that he played a critical role in Tweedy abandoning alcohol at age 23, which saved his career and possibly his life. Indeed, many of us who came up with Uncle Tupelo thought Tweedy succeeded so spectacularly after the breakup, whereas Farrar plateaued, because Tweedy got the savvy manager in the split. Margherita all but steals the Sam Jones documentary about Wilco, as he manages to convince the same record label to pay for the same record (2001's Yankee Hotel Foxtrot) twice, with the band cementing invaluable indie cred by streaming it on its website for free in between the two deals. Let’s hope Tweedy has more books in him, and that a future book delves into this complex, productive relationship.

Perhaps I think this because I owe Tony Margherita so much myself. He showed me how to book band tours like he booked for Uncle Tupelo, and I spent ten years on the road playing rock music based on what he taught me.

Also, I owe my career as a journalist to him. When my old band Enormous Richard opened for Uncle Tupelo at the Blue Note in Columbia, I wrote about it and shared the story with Tony, just for fun, and he told me to send it to the Riverfront Times. “They broke our band and are proud of it,” he told me. “I bet they’ll take it.” He was right; it was published on June 5, 1991.

That was the first time I was paid to commit journalism, and I have been paid to write ever since.

Chris King, now managing editor of the St. Louis American, is a former contributor to the Riverfront Times. We're happy to see him in our pages once more.

Jeff Tweedy's Book Chronicles His Struggles with Mental Illness, Addiction — and Both Jays

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "41932919",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100

}

]