So he is. Turner will be 70 years old this November, but he's incredibly fit and trim and looks years younger than the calendar would indicate. As for his clothes, he is, in the parlance of Miles Davis -- another famous area musician who had, shall we say, a reputation -- clean as a broke-dick dog. Turner is wearing gray slacks, a gray cashmere sweater and a jewel-encrusted watch. Around his neck, somewhat surprisingly, is a shining silver-dollar-sized Star of David.

No, he hasn't converted. Turner has been wearing such a necklace since 1958, when he was given one by the Bihari brothers, the record-label owners for whom Turner produced artists such as Sonny Boy Williamson and Elmore James. "The one they gave me had diamonds on it," Turner says, "but somebody snatched it, so I got another one. I [wear] it for luck, man."

These days, Turner is on the comeback trail; at the time of the interview, he was using the South by Southwest Music and Media Conference to help get back into the spotlight. Though SXSW is ostensibly a place for the music industry to discover new talent, Turner's showcase performance the previous night at Antone's was definitely the place to be. It was packed wall-to-wall with such luminaries as David Hidalgo and Cesar Rosas of Los Lobos, country singer Rick Trevino and reporters from many major newspapers and national magazines, each of them eager to see the infamous Ike, as notorious for being a badass mother as he is for quite possibly inventing rock & roll.

Turner knows there are obstacles to overcome. First, there are all the years of inactivity. His new album, Here and Now -- due to be released next week, two days after he is inducted into the St. Louis Walk of Fame and performs that night at the Pageant -- is his first proper U.S. release in more than 20 years. He lost a lot of that time to cocaine abuse, which eventually landed him in prison at the very time he was being inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. It's not out of the realm of possibility that he has simply been away too long. On a plane flying into Austin before the conference, one music critic struck up a conversation with members of the Beatnuts, a well-known rap group, and Turner's name came up. "Ike Turner?" they said. "Who's that?"

"A lot of kids, they don't know my music," Turner admits. "They might know me. They know my name. But the mistake I made was those years I was away, doing nothing, scared to go play. I ain't scared no more. I want to give what I got before I leave here, man. That's what I'm trying to do. It ain't about money; it ain't about nothing. It's a form of giving for me."

Such talk might raise some eyebrows, coming from Turner, who was portrayed in Tina Turner's scathing memoir, I, Tina, and the biopic What's Love Got to Do With It as a trash-talking, bitch-slapping über-pimp. Turner is understandably reluctant to hash over such matters but finally waves his hands and says, "OK, I'll go there for you. You have to understand, my personal life is really my personal life. And a lot of that is old news. But what I really regret, man, is that during the time I was doing drugs, I signed a contract with Walt Disney, thinking it was for somebody to play me in the movie with Tina. I thought she was going to play herself. And she didn't want to do it with me, so I didn't care who she did it with. So I signed the contract for a measly $45,000. Until I got clean and got my head on like it is now, I didn't realize that the paper that I signed -- my own lawyer got me to sign it -- I was signing away my rights to sue them, and they could portray me any way they wanted to. So they made a villain out of me. I'm nothing like that movie."

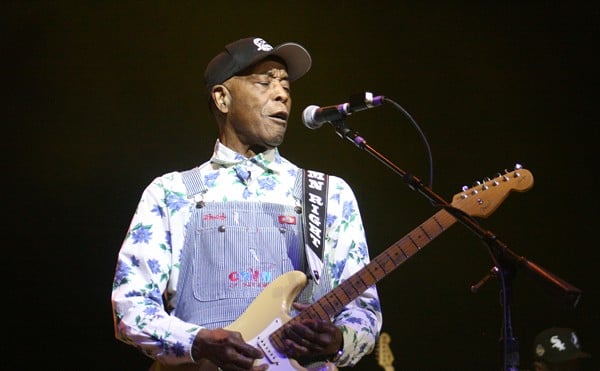

Healthy and happy -- Turner punctuates his conversations with a rooster's crow of a laugh that is always at the ready -- he does indeed seem a changed man. Musically, he's revivified as well. During his show at Antone's, Turner fronted a smoking eight-piece band featuring two keyboardists -- three, once Turner sat down to play piano. Dressed in matching suits and wide-brimmed fedoras, they played old-school R&B that crackled with the intensity of early rock & roll. Turner also played guitar, throttling his whammy bar in his distinctive style, and sang with abandon, something he always seemed reluctant to do during the Ike & Tina years.

It was a long road back for Turner to rediscover the kind of music that made him famous. Even back in the old days, he was always intent on keeping up with every musical style, making his band a living jukebox, pumping out the hits of the day by the Coasters, the Supremes, the Marvelettes, Aretha Franklin and so on (even "Proud Mary," recall, was a cover version). Eventually, though, contemporary music passed Turner by, and, by that time, so had the original style he had forged many years before.

"I forgot what I was playing in St. Louis," he says. "I forgot how to play it. I was in London some time ago, and this woman who owned a magazine there, she said, 'Ike, why don't you do some of the earlier stuff that you used to do?' I said, 'Man, who wants to go backward?' -- you know, 'cause I couldn't stand listening to stuff I did back then.

"Then I went on the road with Joe Louis Walker, and he said to me, 'Do me a favor. Play some of the stuff you used to play, that 'Rocket 88' and 'Prancin'.' He said, 'Why don't you do three of those songs and two of the others?' I said, 'OK.' So I went home to California [Turner now lives near San Diego], and I bought the records and I sat down to listen to them. And, man, I could not play my own stuff. It took me a while to learn it again, and when I did, I really, really liked it."

Around the same time, Turner was introduced to Robert Johnson, who owns a record label called Bottled Majic (as well as subsidiaries IKON, Rooster Blues and Okra-Tone). "I was telling him, 'Man, this is the stuff I should have never stopped playing.' And I was telling him, 'Today, it's so hard for R&B music. The only time you hear good R&B music is on oldies-but-goodies stations.' And I told him that I was going to dedicate the rest of my life to getting black music back on the radio. He thought it was fabulous that I had this desire to do that, so we made a deal to put out a record. And now I'm just concentrating on doing what I used to do."

Izear Luster Turner Jr., born on Nov. 5, 1931, in Clarksdale, Miss., had a tumultuous childhood. After a severe beating by whites, his father died slowly and painfully as a result of his injuries. Between the ages of 6 and 12, Turner was sexually molested by two older women. He grew up hustling for money -- he bought a delivery truck at age 9 and at 10 was making and selling moonshine whiskey.

Even before that, music had put a hand on him. His mother bought him a piano when he was 7, and he learned to play, thanks in part to blues pianist Pinetop Perkins, who taught him some licks. In high school, he formed an R&B group, the Kings of Rhythm, and sat in with the likes of Robert Nighthawk and B.B. King. Turner played piano on King's first No. 1 hit, "Three O'Clock Blues."

In the early '50s, Turner became a talent scout for both the Bihari brothers and Sam Phillips of Sun Records, with whom he would record the seminal hit "Rocket 88." "Back in the day, with all of us in the car, it was like six or seven of us going to play a gig," Turner says. "And we used to make bets -- we'd bet each other a dime or a quarter. I would bet you that I would see more Fords on the road, and you would bet me you would see more Chevrolets. I talked to Sam Phillips on a Monday, and we were going to go up to Memphis on a Wednesday. On the way up, we said, 'Man, what are we going to record?' But on that trip, I said, instead of betting who sees more Fords or Chevys, 'I bet you don't see 12 Oldsmobiles from here to Memphis.' Oldsmobile was new then. So this is how the 88 thing come up. We started writing the song in the car. By the time we got to Memphis, we was almost finished writing it, and we finished writing it in the studio. It took me 10 or 15 minutes to put the music together."

Jackie Brenston took the vocal on the song and was listed as the bandleader on the record. The song rose to No. 1 on the charts and was the top jukebox number at the same time. In the end, Turner was paid all of $20 for the song.

Turner continued writing dozens of songs, producing and playing on sessions for others, including Little Milton Campbell's first recordings in 1953, which were also made at Sun Studios. In 1954, Turner came to visit his sister in St. Louis. He went clubbing across the river, to Nick's Country Club and to Ned Love's. Soon after, he returned with his band, played a gig at Love's and was asked to play again the next night. Eventually Love asked the band to move up, and they did. "That was the beginning of St. Louis, man," Turner says. "When we started playing, St. Louis was basically a jazz town. There was Jimmy Smith and some big bands that I've forgotten the names of. Chuck Berry was the only band that was playing any kind of music that was not really jazz or blues, but was rock & roll kinda stuff. So then, man, I started playing all over St. Louis. I met George Edick, who had the Club Imperial, and we started working there on every Tuesday night. Next thing I knew, we were working 13 jobs a week in St. Louis. And then we were broadcasting music live on KATZ. Finally I bought a house in East St. Louis, and St. Louis just got to be my town. We just had fun, fun, fun."

The house in East St. Louis became a residence for most of the band. It was also a rehearsal space and, with four bedrooms, party headquarters. That led to some rough goings-on, mostly caused by jealous boyfriends or husbands. Sometimes gunplay was involved. "You know how it is when you get popular," Turner says. "I don't know how to say this, exactly, but girls started pulling at you and stuff, and you don't stop and ask whether they married or not, and some of 'em were. Guys used to come by and shoot up against my house. They called that house the 'house of many thrills,' and it was."

But Turner's gigs, popular as they were, also became a testing ground for social change in what was then a mostly segregated city. "St. Louis was kind of prejudiced then, man," he says. "But kids, they didn't care nothing about race. They were just into music. At that time, George Edick's didn't have blacks there, and over in East St. Louis at Club Manhattan, they didn't have whites. So what I started doing, man, was, I stopped playing any black club that wouldn't allow whites and any white club that wouldn't allow blacks. The dollars don't have no color, so the club owners started letting everybody get in there."

Turner discovered Anna Mae Bullock at one of his local gigs -- coincidentally, at a place called Turner's Hall -- and she eventually came to sing with the group as Tina Turner (though Ike staunchly maintains the pair never married). They had a hit together with "A Fool in Love," a song that was originally meant for R&B vocalist Art Lassiter.

"I wrote the song for [Lassiter]," Turner recalls. "Tina was there as I was writing it. And this guy, he was going to beat me out of some money, man. He borrowed, I don't know, $80 or $90 to get some tires for his car, and he had no intention of paying that money back. So we went out to Technisonic Studios. They never did any live bands there; all they did was TV commercials and stuff. We waited on Art, and he never showed up. So Tina said, 'Why don't you put my voice on there, and when you find him, you can put him on instead.' So that's what we did. When Tina got to the part where she makes that scream -- 'Hey, hey, hey, wowww!' -- Ed, the guy who owned the studio, like to hit the ceiling: 'Goddammit, don't holler in my microphone!' In those days, they didn't have no limiters. I guess she rammed the needle. It was real funny.

"But that was the beginning. There was a disc jockey there called Dave Dixon. After I recorded the song, I went out to Club Imperial, and we played it out there for some of the kids on a little recorder in the car. They said, 'Man, why don't you put it out with her voice on it?' So Dave Dixon heard it that same night. He sent it to Sue Records; they put it out, and boom, it was a hit."

Other hits, such as "I Think It's Gonna Work Out Fine" and "Poor Fool," followed. In 1962, Turner left the St. Louis area and moved his base of operations to Los Angeles. The Ike & Tina Turner Revue became an international sensation, opening shows for the Rolling Stones (including the infamous Altamont concert). They peaked creatively in 1966 with "River Deep, Mountain High," which Tina recorded with Phil Spector, and commercially in 1971 with their No. 4 hit "Proud Mary."

But with success came the dark period recounted in excruciating detail in I, Tina and in Ike's own harrowing memoir, Takin' Back My Name. Ike had always had a temper, but when he began using -- and then abusing -- cocaine, what was left of his creative genius began to dissolve. So how did a man who once would have fired band members for drinking or having drugs in their possession wind up hooked himself?

"Well, man, when it started off, there were two people -- they both are dead now. I won't call their names, 'cause I don't want to put a black mark on them. They gave me a little thing of cocaine, and I put it in my coat pocket, and I carried it there for months. I never tried it. They told me, 'You'll like this.' Occasionally I'd take a little drink of whiskey or some wine, but not enough to even bother me. And that's like maybe once every four or five months, not every day. So, finally, one day I was thinking about it. I went and got it and I asked my doctor about it. He told me the pros and cons. So I sat up one night when we was working, and I put some in my nose. This was like 2 o'clock at night. Eleven o'clock the next day, I'm still sitting at that damn piano, feeling like I just woke up. I felt like it was making me really ambitious. I had a lot of energy.

"The next thing I knew, I was waking up looking for it. Everywhere we'd play, I'd have a big bowl of cocaine there, and people would steal it. I was all mental. And then the next thing I knew, I had a hole through my nose. After that, I started smoking it. And then, man, all I did was sit up philosophizing and procrastinating. I started going downhill; my whole career went downhill. I used to pray, man, that if I could just get by three days without it, I would never do it again. But I would always lie to myself and say, 'Oh, Tommy's coming over, or Jan is coming over; they're going to want some,' and I'd order some. The best thing that ever happened to me was when I went to jail. When I went to jail, I got my three days. That was the last time, in '89. I haven't looked back since. Anybody that's doing drugs, that's hooked on drugs -- well, all I know about it, cocaine -- they want to get off. But addiction, man, it's unreal. A lot of people hit rock bottom, they think that they can't get up. But I'm a living example, man. I hit rock bottom. I went all the way down. The best thing that ever happened to me was me getting my life back."

With the changes in Turner's personal life and his current musical resurgence, his comeback is complete. But his life still has its odd twists and turns. He was stopped by a policeman recently while driving from St. Louis to California at a particularly dangerous clip. "I was driving 120 mph," he says with a laugh, "and he had been trying to catch me for 30 or 40 miles. So finally some trucks had me blocked so I couldn't get by. Then, there he was, right on my bumper. He asked for my driver's license and said, 'Ike Turner ... oh man.' He didn't give me a ticket; he just said, 'I just want to thank you -- you've given us so much.' As we got to talking, it turns out he was conceived -- his mother and daddy got him -- on a night that they came to an Ike & Tina concert. Another policeman stopped me one time when we were doing 110. Believe me, in my car, you can't tell you going that fast. So when we got pulled over, you know what he wanted? He didn't give us no ticket. He just wanted me to give him a hug!

"All in all, though, I don't regret any part of my life, because it took it all to make me what I am today. And I love me today, man."