The past few months have been about making up for lost time for sixteen-year-old Karla and her family. The Honduran national with a baby face and a radiant smile hasn't lived under the same roof as her parents since she was an infant, and she's only met her U.S.-born brother once, when he came to visit her years ago. That changed in June when Karla arrived to her family's St. Louis home, after being one of thousands of undocumented minors detained along the U.S.-Mexican border this year.

The year after Karla was born, her parents made the trek north to the United States looking for employment opportunities that didn't exist in their native Honduras, a country that's routinely ranked as one of the poorest in the Western Hemisphere. After brief stints in Texas and Florida, Karla's parents finally settled in St. Louis. Her mom, Ilsa, found work cleaning homes and hotels and eventually earned a visa to legally stay in the U.S. Karla's father found a job in construction despite remaining an undocumented immigrant. (Because of this, Riverfront Times has agreed to not use the family's surname in this story.)

Together Karla's parents earned enough in their adopted homeland to rent a house in north St. Louis County. They also had a second child in St. Louis, a now twelve-year-old son, who, like many American kids, is constantly glued to his Game Boy. Missing from the family was Karla. She remained with her grandparents in Honduras.

Karla's parents would wire money to Honduras on a regular basis to pay for their daughter's education, clothes and little extras like cell phones and CDs of Christian music. For fifteen years it remained this way with Karla knowing her parents primarily though phone calls, letters and Western Union transactions. (A few years ago Karla's father was deported, but the forced homecoming was a short one. He returned to the U.S. within a few weeks so he could keep his job in St. Louis.)

Recently, things have changed in Honduras. Gang violence, fueled by the drug war, has made it increasingly dangerous. The Honduran city of San Pedro Sula, which has the highest murder rate in the world, lies just an hour away from Karla's hometown of Pimienta. Karla's grandmother began worrying that, were she to remain in Honduras, Karla could add to the growing number of victims of violent crimes in the small Central American country.

"There are police, but not enough," says Karla, who notes that even law enforcement can't be totally trusted in her country. "If you're not careful, they might rob or kidnap or assault you, too."

"When the gangs want to do something, when they have an idea in their head, they do it," adds Ilsa. "The police won't stop them. They're too afraid."

Today Karla's parents see the story of Honduras and their daughter's flight to safety as part of a larger story about the United States' controversial immigration strategy and the legacy of its foreign policy in Latin America. But this past May their decision to get Karla out of Honduras was based only out of concern for her safety.

"We had thought about [bringing Karla to St. Louis] for many years," says Ilsa. "But we didn't do it before because of the danger of crossing Mexico. Now we see that the danger and risk is in Honduras, too."

Karla's departure wouldn't be easy for her grandmother, who couldn't stand the heartbreak of saying farewell to Karla. She never did. Instead, with her grandparents' blessing, Karla's parents arranged for their teenage daughter and their eleven-year-old nephew, Jonathan, to leave Honduras unannounced without so much as a final goodbye. The journey began May 22 when Karla and her cousin boarded a bus for San Pedro Sula en route to meet the coyote who would secure their passage to the Texas border.

THE TRIP NORTH He went by the nickname Pelón, Spanish for "baldy," and for the next few days this short, chubby man with a serious demeanor would control nearly every move for Karla, Jonathan and some 35 other migrants journeying to the United States. Karla's parents had saved up $3,000 to pay Pelón for their daughter's 1,500-mile trek across three countries.

In San Pedro Sula, Pelón had Karla, Jonathan and the others board a bus for the short trip to the Guatemalan-Honduran border. Once there the coyote had taxicabs waiting. Karla and the others squeezed into the cabs, with as many as ten people in one vehicle, for the short trip into Guatemala. What the border crossing lacked in comfort, it made up for in ease.

"I don't know if the taxis have an agreement with the guards, but they didn't give us any problem crossing," Karla recalls of the border agents.

A few miles into Guatemala, the taxis dropped off the migrants at a bus depot for the next leg of the journey — a six-hour ride to the Usumacinta River.

The Usumacinta is a common way to enter Mexico from Guatemala and vice versa. Tourists on their way to or from the Tikal ruins can take the trip for about $12, provided they have a passport that isn't from a Central American country. But for people from Honduras and southward on the isthmus, crossing the river is illegal without a visa. Again, Pelón would provide.

The coyote arranged for several boats to ferry the migrants across the river in the same brightly colored vessels used to transport camera-toting American and European tourists.

"When we got on land, there were several taxis waiting again, just like last time," Karla says. "And Pelón told us to get in the cars extra fast."

They did as they were told. Once Karla's cab got moving, she remembers the driver flooring it and barely acknowledging the several passengers crammed into his car. The destination was the top of a small mountain nearby. Each taxi drove to the top, let the passengers out, and drove back down the mountain.

Then Pelón told the group the plan: Because state police were under increading pressure to nab migrants, Mexico would be by far the lengthiest and riskiest part of the journey. And the Mexican-Guatemalan border was teeming with federales, especially during the day. They would wait at the top of the mountain until dark. Then the taxis would come back and get them.

As night fell, the headlights of the same taxis they'd taken earlier in the day began illuminating the dark mountaintop. This time the cab drivers leisurely drove the mountain roads to a hotel in the Mexican state of Chiapas. Pelón had booked some rooms and provided sandwiches. Karla and her cousin slept in a room with several women until morning, when a couple of microbuses came to pick up the migrants and continue the trip.

Still close to the Guatemalan border and in a hot spot for Mexican police, Pelón moved his charges from vehicle to vehicle using taxis and small buses for the roughly six-hour trip to the gulf city of Veracruz. After arriving there, Pelón handed each migrant a ticket and they boarded a coach with comfortable seats and air-conditioning typical of long-distance bus travel in Mexico. Their destination was now Matamoros, the border town that sits along the Rio Grande across from Brownsville, Texas.

After a few hours of travel, Karla recalls, the bus was stopped for an immigration check. An official came on board to look at passengers' IDs. This is the place where many migrants are caught if they attempt to take the tourist buses. But the immigration inspector looked the other way when it came to Pelón's group.

"They didn't even talk to us," Karla says. "They talked to Pelón and seemed to know him."

A similar scenario would play out at another immigration checkpoint before the group at last reached Matamoros, and Pelón — his part of the job complete — left the group at a safe house inside the cluttered, and sometimes violent, border city.

Now the migrants were in the care of a man covered in baggy clothes and tattoos who looked like the type of cholo (a colloquial term for Latino gang-bangers) that Karla and her family feared in Honduras.

"You're going to wait here until it's time to cross the border," the man informed Karla and the others. "We'll go in separate groups. Everyone can't go at once."

For the next few nights, the migrants would stay at the small and dirty safe house with its disheveled furniture and cold ground. Karla remembers the ground because it's where she and her cousin sat and slept. Outside the house, a few chickens roamed about the yard. That's where their new coyote would spend most his time — smoking marijuana and staring at the poultry.

But the safe house wasn't a prison. Before Pelón left, he gave each migrant about $40 worth of pesos to buy food at a store down the street and call their loved ones. As soon as she was able, Karla phoned her parents to let them know she was all right.

"You need to call your grandmother," Ilsa told Karla. "She's worried about you and needs to hear your voice."

The stress of Karla's departure had caused her 82-year-old grandmother to check into a hospital. Karla tears up thinking about the call she made to her grandmother, and how she reassured the woman who'd raised her that she was OK and would be with her parents soon. In truth it would take Karla many more days to make it to St. Louis, and she'd arrive by plane — courtesy of the U.S. government.

WAITING IN LIMBO The morning after Karla's call to her grandmother, the coyote informed her and Jonathan that they would be in the first group to cross the Rio Grande. Along a riverbank just outside Matamoros, the coyote told Karla, her cousin and about ten other migrants to get on an inflatable raft. Neither Karla nor her cousin know how to swim, and the two minors clung to the raft as the others slowly paddled the boat across the narrow stretch of river.

The next few minutes passed in a blur. Karla remembers landing on the Texas side of the river and following the group into the bush to hide. The border agents seemed to pop out of nowhere. Karla and the other migrants were immediately surrounded. The coyote, meanwhile, seemingly disappeared.

"I never saw him be put under arrest," Karla says. "They took us away, and I never saw him again."

At the Port Isabel Detention Center outside of Brownsville, authorities put Karla and Jonathan into quarters segregated by gender. It was the first time since leaving Honduras they were apart.

"When they took him away, I begged for them to stop, I told them I had to watch him," Karla says. "But they didn't listen to me. They took him and put me in a cell with other women."

Karla and her cousin would spend the next two weeks in the detention center, and the memories of their time there still haunt the teenager. Karla was forced to get her long brown locks cut down to her shoulders. Later, she says, she became sick, and the staff ignored her complaints of stomach pains and nausea, and refused to provide her with medication or treatment.

"They treat you like animals, no respect," says Karla in Spanish. "It was ugly, dirty. I just wanted to leave."

Finally, after two weeks, Karla's mother was able to get legal sponsorship of her daughter under a somewhat unusual arrangement stemming from a 2008 law intended to crack down on human trafficking. Under that law, minors from Central American countries who are caught crossing the border are channeled through the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services instead of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. The process typically allows for these minors to spend months in the U.S. before being deported and, as with Karla, live with their families as a cost-savings solution.

"[The government] doesn't want to detain her. She's not mandatory detention," says St. Louis immigration attorney Jim Hacking, who is not involved with Karla's case but spoke to Riverfront Times about how they generally work. "She's someone in deportation proceedings in the United States, so they release her to her mother's care as opposed to detaining her."

Jonathan's mother, who also lives in St. Louis, was able to get sponsorship of her son. With their paperwork settled for now, immigration officials took the two minors to the airport and put them on a plane bound for St. Louis.

Karla arrived June 19. Ten weeks later, Karla and her folks look every bit the prototypical family at their north-county home. Her brother plays video games in his bedroom, her father tinkers with the car parked out front, and her mother makes a pot of coffee. Hanging over Karla and her parents, however, is the court date in a few months' time that — in all likelihood — will send her back to Honduras.

"Generally, she'll probably get deported unless she can show she'll suffer particular harm in returning," notes Hacking. "And the reason can't be just that it's bad for everyone in Honduras."

UNINTENTIONAL ACTIVIST Karla is one of more than 52,000 undocumented minors to illegally cross into the United States from Mexico this year. The unprecedented flood of these juvenile immigrants has riled up many U.S. citizens who've demanded that the government tighten the border.

Yet the argument can be made that the U.S. is as much to blame for the border crisis as the undocumented immigrants who flout international law in their quest to reach the states. And that's especially true when it comes to Hondurans, says Dan Hellinger, a professor of international relations at Webster University who specializes in Latin America.

Hellinger explains that the current crisis in Honduras and other Central American countries is partly a result of the U.S. government's war on drugs and its interventionism in the region.

"The violence in Central America affecting the children has its roots in the 1980s, the [civil] wars," Hellinger says. "Some of that has to do with the networks between gangs dealing drugs in California and the trafficking through Central America. Certainly, some of the arms in the region are arms that went there in the 1980s."

The gangs that are wreaking havoc on Honduras were formed in the U.S. and strengthened during the 1980s with help from drug profits. The war on drugs caused many gang members to get deported, which led to the expanded networks in Central America.

"We know a lot of the gangs that are now perpetrating violence were originally created by those young people when they returned from the United States," says Hellinger.

Meanwhile, the Webster University professor says, the U.S. backing of right-wing groups in the region brought a large influx of weapons and government militarization, which has contributed to the violence.

All of this has directly impacted Karla and her family who felt they had to leave Honduras regardless of the consequence they'd face in the U.S. For years Karla's parents have been active with Latinos en Axion, a St. Louis group that seeks immigration rights for Hispanics.

"There aren't many of us here, not like Chicago or even Kansas City," says Leticia Seitz, who co-founded Latinos en Axion after arriving in St. Louis from Mexico. "But we are here, and if we can unite, we can have a better chance of helping to change things."

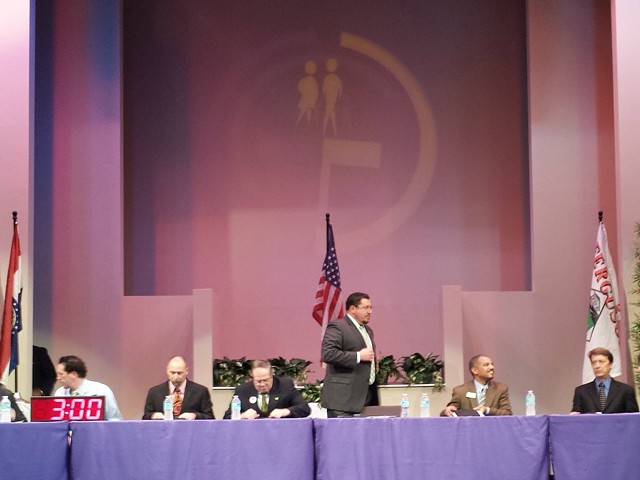

One of the ultimate goals of the group is to get amnesty for immigrants such as Karla and her father that would allow them to legally stay in the U.S. When Karla arrived here in June, Seitz and others in Latinos en Axion felt it would be good to get her story in front of a broader audience. In early August Karla joined academics and activists on a panel discussing immigration reform at the Missouri History Museum. The sixteen-year-old looked a bit out of place seated at the table with adults three and four times her age. But she confidently told her story through a translator.

Karla ended her tale with a plea. "We have to find real solutions for [other immigrant kids] and me," she told the audience.

In a small but significant way, Karla found herself fighting for her rights. After the panel concluded, someone in the crowd handed Karla a bouquet of flowers.

Last month Karla began taking catch-up classes to prepare her for high school. She's interested in becoming an engineer and is taking English lessons. She's learning quickly with the help of her American brother. But as she waits for her court date, the prospect of having to go back to Honduras looms heavy.

"I hope I can stay here with my family. I don't want to be separated from them again," Karla says. "I'm scared. I don't know what will happen if I have to go back."

Follow Ray Downs on Twitter:

E-mail him at [email protected].