No one could find Brian Dorsey the day after his cousin Sarah Bonnie and her husband Ben Bonnie were found murdered. The couple had been shot to death in their home in New Bloomfield, Missouri, where Dorsey had been the night before. Some thought Dorsey, who had struggled with mental illness and substance abuse for more than half his life by that point, had killed himself.

He tried twice before, and his parents, who failed to find Dorsey at his apartment during the chaos of that day, believed maybe he had been successful this time. Larry and Patty Dorsey, now both deceased, knew Dorsey was at the Bonnies’ on December 23, 2006, the night of the murder, according to court documents. Whether their son had anything to do with the killing of Sarah and Ben Bonnie was yet to be confirmed.

It wasn’t until 11 p.m. on Christmas Day that Dorsey called his mother. He said he was preparing to kill himself. Dorsey has long maintained he has no memory of the Bonnies’ death. But after another conversation with his mother, they both agreed he would turn himself in.

Two days after the killings, Dorsey told police he was “the right guy” for police to talk to concerning the Bonnies’ deaths. Whether Dorsey committed the murders has never been questioned in court. But Dorsey has never denied it.

“Even though he doesn’t remember it, he has never challenged it,” says Megan Crane, co-director of the MacArthur Justice Center. Crane is Dorsey’s local counsel in addition to attorneys with the Pittsburgh-based Capital Habeas Unit.

“It’s really important to him to take full accountability,” Crane says.

Still, more than 17 years after the killings, his attorneys argue Dorsey’s conviction was invalid — and that the state should not carry out his scheduled execution on April 9.

Dorsey has petitioned the Missouri Supreme Court alleging he was pressured to plead guilty to two counts of first-degree murder by attorneys who wanted to expedite the trial. His lawyers today argue that it was impossible for him to satisfy the requirements of first-degree murder because he was suffering from drug-induced psychosis. Due to the shortcomings of his trial counsel, their pleading is the first time any court has been presented with compelling evidence from independent experts that Dorsey experienced such psychosis on the night of the murder.

Dorsey, 51, has lost appeal after appeal in the years since he was sentenced to death. The reality is Dorsey will likely lose again. The Missouri Supreme Court rarely grants relief in petitions such as Dorsey’s. Even slimmer is the chance Governor Mike Parson would grant him clemency.

Dorsey’s is the first execution date requested by Attorney General Andrew Bailey after a slew of executions requested by his predecessor, Eric Schmitt, who is now a U.S. senator.

During Schmitt’s time in office, Missouri became one of few states to ramp up its use of capital punishment as others either restricted the practice or death sentences became rarer in courts.

Dorsey would be the seventh Missourian to be executed in the past two years, should his execution proceed. The other six also offered good reasons for relief (and one, Kevin Johnson, even convinced U.S. Supreme Court Justices Ketanji Brown Jackson and Sonia Sotomayor to file a blistering dissent seeking to stop his execution).

But despite a growing movement among Missouri Republicans to stop the death penalty, none of those executions were stopped, and it’s unlikely Dorsey’s will be either.

Some of the people who loved the Bonnies have no problem with that.

Jacob Bonnie was 30 when his little brother, Ben Bonnie, 28, was killed.

“He was my best friend,” Jacob Bonnie says.

Court records paint a horrifying narrative of the night of the Bonnies’ murder. Sometime after the Bonnies went to bed, prosecutors say, Dorsey took a single-shot shotgun out of their garage and fired a fatal blow at his cousin's jaw from about a foot away. He then emptied the chamber, reloaded the gun, pressed it against Ben Bonnie’s ear, fired, and allegedly had sex with Sarah Bonnie’s body. and allegedly had sex with Sarah Bonnie’s body. (Notably, Dorsey was not charged with or convicted of sexual assault.)

“To me, somebody like that doesn’t deserve to wake up the next day,” Jacob Bonnie says.

At the center of Dorsey’s last-ditch effort for life is the question of whether his previous attorneys represented him effectively. Since Dorsey's conviction, the Missouri State Public Defender’s office has abandoned what’s now widely considered the unethical practice of contracting attorneys for flat fees in death penalty cases.

Dorsey’s initial two attorneys were paid $12,000 each — whether his case went to trial or not. Capital cases in the early 2000s averaged 3,557 hours of work, a 2010 report prepared for the Judicial Conference of the United States found. Dorsey’s attorneys would have been paid just $3.37 per hour had they put in the expected amount of work.

Only they didn’t. At least, that’s what Dorsey’s attorneys hope the Supreme Court will conclude.

The flat-fee arrangement was a conflict of interest that disincentivized Dorsey’s attorneys to provide effective representation and led them to “pressure” Dorsey to plead guilty to first-degree murder with the death penalty still on the table, his new attorneys argue in a brief filed with the Missouri Supreme Court.

His trial attorneys never asked him the most “basic” questions about himself or that night that ABA guidelines require for effective counsel. Had they done so, Dorsey’s current attorneys argue, they would have known he was incapable of first-degree murder. Yet Dorsey pled guilty to first-degree murder in exchange for nothing from prosecutors.

“That defense stood to benefit financially if Mr. Dorsey pleaded guilty rather than use attorney hours and resources on a guilty phase proceeding is indisputable,” the petition states. “This reality undoubtedly led to counsel’s failure to effectively act as an advocate for Mr. Dorsey in any way.”

This argument isn’t a new one. In a review of Dorsey’s post-conviction petition, the state Supreme Court found that Dorsey did not prove the flat-fee arrangement led to any conflict of interest.

The same argument came up in the case of Michael Tisius. Perhaps by no coincidence, Dorsey and Tisius had the same two attorneys.

Chris Slusher and Scott McBride were each paid a flat fee of $10,000 to represent Tisius for what should have been five years of work leading up to his capital sentencing hearing, according to the American Bar Association, or ABA. The director of the state Public Defender’s office urged Parson to grant Tisius clemency for this reason.

As did ABA President Deborah Enix-Ross. The ABA has no broad stance on the death penalty but will oppose certain convictions. The association also encourages against executions of defendants who were 21 or younger at the time of their offense.

Tisius, who was 19 at the time he shot and killed two jailers, was executed for the murders last June.

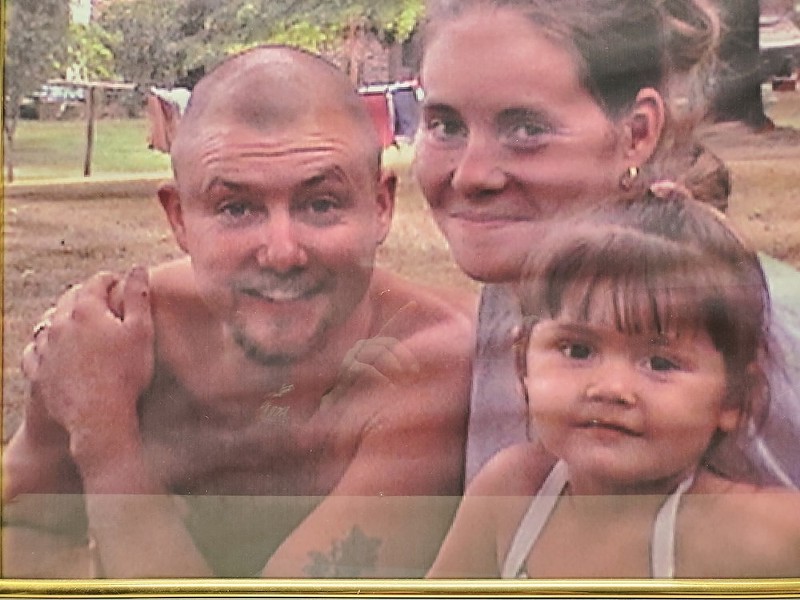

On Christmas Eve 2006, the Bonnie family waited for Sarah and Ben Bonnie to show up at their parent’s house for an 11 a.m. get-together. They were late, which wasn’t a surprise because Ben Bonnie was late “all the freaking time,” Jacob Bonnie recalls.

Phone calls went unanswered, so Jacob Bonnie’s wife and father decided to drive to his brother’s house. By the time they arrived there were cop cars everywhere. Now Jacob Bonnie’s wife and father were the ones not answering their phones.

Jacob Bonnie knew something was up before they even returned back home. He and his mother were taken to separate parts of the house and given the news — he by his wife downstairs, his mother by his father upstairs.

Every day since has been hard, Jacob Bonnie says. He talks about his two sons and how they would’ve loved their uncle; how Ben Bonnie, “a family man,” spent with family on camping trips and motorcycle rides.

“It was really hard for my parents mostly,” Jacob Bonnie says during a phone interview. “To have a child die before you do, it’s just out of sequence. Every holiday, we have those two empty chairs.”

RFT attempted to reach members of Sarah Bonnie’s immediate family through public phone records. According to her obituary, she was survived by her parents, two sisters and a brother. One sister used an expletive to tell a reporter to go away and said to never contact her family again.

It was Sarah Bonnie’s parents who found her first. Her father had jimmied the lock on one of the master bedroom doors to see his daughter and son-in-law dead on their bed, according to court records.

The master bedroom was in disarray. An investigator alleged he smelled bleach (and though other investigators testified they never smelled it, prosecutors later alleged it had been poured on parts of Sarah Bonnie’s body). Results from a sexual assault kit eliminated two of the three men she’d been around that night as the source of sperm cells found inside her. The kit did not rule out Dorsey.

Sarah Bonnie wore only a t-shirt when her body was discovered. The gunshots to her and her husband’s skulls killed them instantly. Dorsey had taken Sarah Bonnie’s car, as well as electronics, jewelry and cell phones from the house to sell.

Dorsey later testified he had been awake and smoking crack cocaine for two to three days, and had no money to buy more when he ran out. Drug dealers came to his apartment on the day of the murders demanding money. Dorsey called at least threefamily members for help, including Sarah Bonnie. The reason Dorsey was at their home that night was because the Bonnies had taken him in that night.

“It was just horrible, the things I heard from the detectives and stuff,” Jacob Bonnie says. “To backstab someone who brought you in to help you out… the betrayal.”

At one point in a conversation with a reporter, Jacob Bonnie describes Dorsey as a monster. He says the punishment fits the crime in this case and it’s nice to see the ball finally start to roll on the execution. “For a while you almost wonder if they forgot,” he says.

“I believe in the death penalty and I think he deserves it,” Jacob Bonnie later adds. “But on the other hand, if it didn’t go my way, I could live with it.

“To me, the less I think about him, the less impact he has on my family.”

Had Dorsey’s attorneys launched any inquiry into his life, they would have found a long history of substance abuse and mental illness that reached a pinnacle the night of the murders, his petition states.

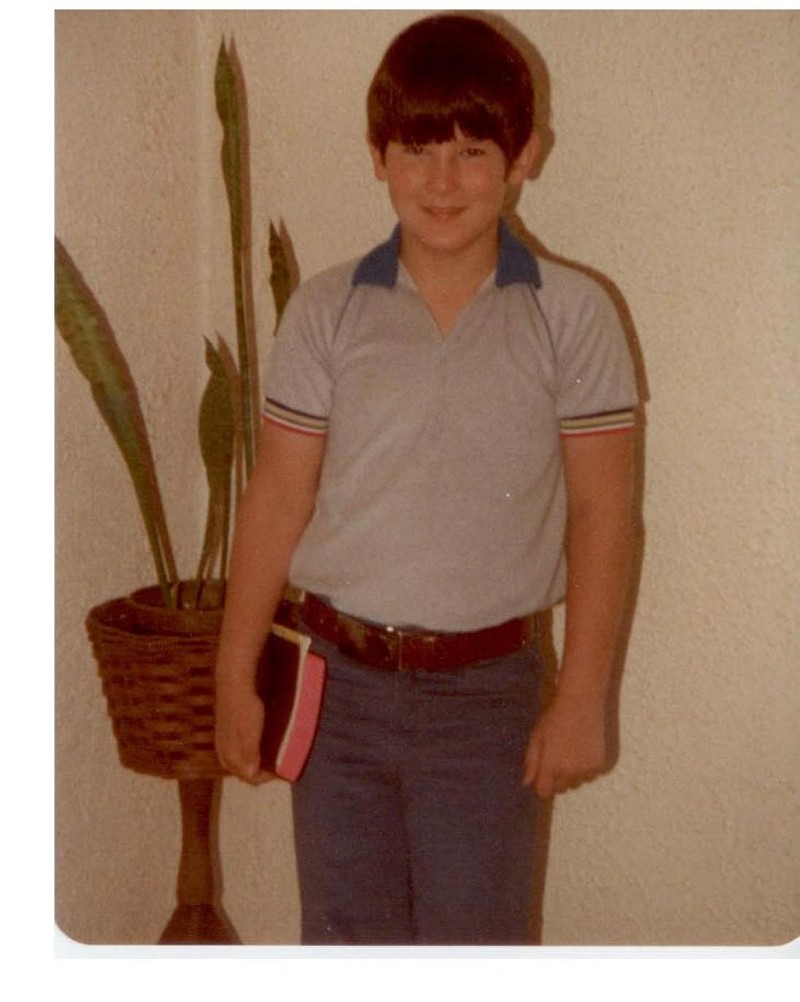

Dorsey started binge drinking in high school after growing up in a home that revolved around his father’s alcoholism, according to an assessment of Dorsey’s substance abuse by Dr. Edward French. He “self medicated” what would later be diagnosed as major depressive disorder with booze and cocaine. By age 19, Dorsey had formed a daily drinking habit that did not stop until he turned himself into police for the Bonnies’ murder 15 years later.

Dorsey tried multiple times to rehabilitate himself, including a number of inpatient and outpatient mental health and substance abuse treatment programs. It didn’t work. Neither did his two attempts to end it all entirely. He attempted suicide in 1992, after which he was psychiatrically hospitalized. The same happened again in 2004 when he failed to take his life a second time.

On the night of the Bonnies’ murders, Dorsey was held captive in his apartment by two drug dealers who forced him to call his family members and beg for money to pay back his drug debts. This was “catastrophic” to Dorsey, who had tried to hide his drug use from his family.

The shame of those phone calls, in part, led to one last binge. On the night of the Bonnies’ murders, Dorsey had not slept for 72 hours, had been drinking copious amounts of both beer and vodka, and was experiencing an “extreme level of intoxication.” Unable to purchase drugs, he was going through withdrawal from crack cocaine. Usually Dorsey isolated himself whenever he was coming down from drugs. He “routinely suffered” auditory and visual hallucinations during previous bouts of withdrawal and the night of the murders was no exception, according to the petition, which says the hallucinations made him a “poster child” for psychosis..

According to the report on Dorsey’s substance abuse, Dorsey’s binging of cocaine led to episodes of extreme paranoia and at times bizarre behavior, including “talking nonsensically in riddles.”

“The fact that he experienced paranoia and hallucinations during his heavy use of cocaine suggests that he was experiencing a cocaine-induced psychosis on the night of the events leading up to his conviction,” French, the report’s author, wrote.

Dorsey has no memory of the crime. Multiple independent experts confirmed a lack of memory is supported by science of what his brain would have gone through at the time.

It’s not uncommon for death row inmates to claim they were not in the right mind at the time of their offenses. What’s significant about Dorsey’s case, however, is that the drug-induced psychosis he experienced that night was never brought up during his trial.

“Brian received essentially no defense,” Crane, one of Dorsey’s current attorneys, says.

If it had, according to Crane, it would have made it extremely difficult for the prosecution to secure a first-degree murder conviction.

To prove first-degree murder, prosecutors must prove murders were carried out with deliberation, meaning there was “cool reflection for any length of time no matter how brief,” according to state statute. But Dorsey was “neurologically incapable of deliberation” because of the psychosis, his lawyers argue.

“Brian is innocent of capital murder,” Crane says. “He was incapable of the mental state or the intent for first-degree murder.”

The petition Crane filed with the state Supreme Court asks it to either overturn his death sentence or appoint a special master to conduct an evidentiary hearing.

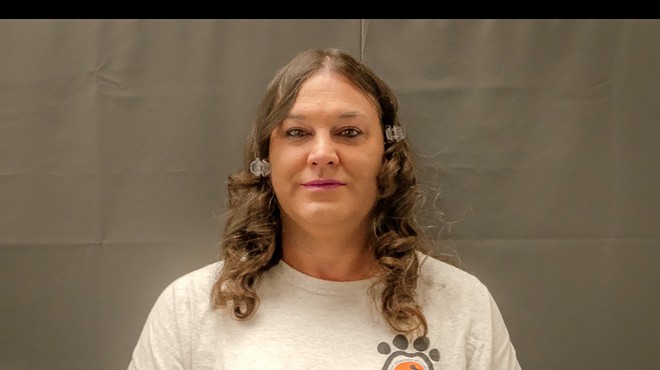

Brian Dorsey is not the same man he was 17 years ago, Crane says. He’s a trusted, respected inmate at Potosi Correctional Center where he remains sober and has a uniquely clean disciplinary record.

“I think deep and pervasive shame and remorse has been the defining aspects of his life ever since,” Crane says. “It’s shaped who he has grown into today.”

Dorsey has never had a single disciplinary action — an unheard of accomplishment in a maximum security prison, according to Crane, where inmates can get written up for things as small as leaving too many salt and pepper packets in their cells.

Prison jobs turn over on a regular basis so incarcerees don’t become too familiar with staff, but Dorsey has been the prison barber for Potosi Correctional Center for over a decade. It’s one of the most trusted positions; he cuts the hair of correctional staff, including current and former wardens.

“He is so respected and trusted by the prison staff, despite the fact that he’s on death row,” Crane says.

Despite the murders, Dorsey remains close with several of his immediate family members. They keep in touch through letters and bi-weekly phone calls, Crane says. But with the exception of his parents, who are now deceased, Dorsey has not allowed family to visit. His father talked to him every week and brought him food.

Keeping other family members away is Dorsey’s attempt to minimize the harm his death could cause to an extent he could control.

“He thinks he’s protecting his family to not let them see him,” Crane says, “He thinks he’s caused them enough harm and wants to create some distance.”

Dorsey has traded letters with his cousin Jenni Gerhauser throughout his incarceration, however. Gerhauser was also a cousin of Sarah Bonnie.

In a clemency video produced by Dorsey’s attorneys, Gerhauser described Dorsey as a “safe space” for his loved ones — and the brother she wanted but never had.

“When you’re with Brian you’re better,” Gerhauser told an interviewer. “You feel better, you feel protected, you feel loved. To have that taken away is really hard. It’s even more difficult when you can’t touch it, can’t get to it.”

Gerhauser has also written to Governor Parson in a plea for Dorsey’s life.

“I love him and do not want to see him killed,” she wrote.

“I wish someone, a decision maker, could see Brian for who he is when not on drugs; he is that person today.”

At least two jurors from Dorsey’s trial have also written letters advocating for Dorsey’s clemency. Crane says that number may grow.

Missouri officials routinely cite the peace of mind that executions give to victims’ families. Some do gain a sense of closure and justice. Some don’t. What’s inevitable is a newfound loss suffered by the loved ones of death row inmates who didn’t want to see their friend or family member die, no matter how horrendous the actions that led to their convictions.

Dorsey, despite his consuming remorse, has found purpose. He sees his barber work as a way to give back, to provide some amount of positivity and light in someone’s day. That, and a desire to protect the family he left behind, drives his fight to live.

“I would say he is fighting [death] as much for his family as he is for himself,” Crane says.

Editor's note: This story was updated a few hours after publication to include correct information about the location of the Capital Habeas Unit. They are in Pittsburgh. We also clarified a few details around the suspicion of bleach being used on the crime scene and around the allegations of sexual assault after Sarah Bonnie's death.

Subscribe to Riverfront Times newsletters.

Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter | Or sign up for our RSS Feed