COURTESY OF SEJLA GRAHOVIC

From left, Sejla Grahovic, her mother Minka, father Hasan and brother Serif.

Before I was a teenager, I lived through terrifying times. I witnessed war. I witnessed torture. Wounded people died before my eyes because they got no help.

My name is Sejla Grahovic. I was born in Bosnia, in a small town called Velika Kladuša, on November 19, 1984. I immigrated with my family to America in 1998 to escape a war. The horrors of the war forced us to leave everything we knew and loved.

From 1992 to 1996, Bosnia was involved in a war with neighboring countries, which had once all been the same country, Yugoslavia. In 1994, we left our home to live in a refugee camp. Our food, mainly canned goods, came from the United Nations. We slept on the bare floor. Soon we picked grass to sleep on to make it more comfortable. We bathed and washed our clothing in the river and used the cornfield for our bathroom. Then the door opened for us to enter the United States, and that’s how I became a refugee at thirteen.

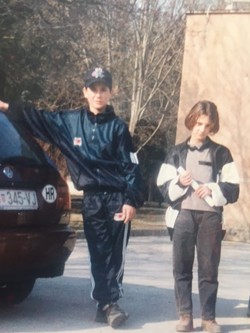

COURTESY OF SEJLA GRAHOVIC

The author and her brother in Europe, waiting for permission to come to the U.S.

Starting a new life in a country that we knew nothing about terrified us in a different way. There was no war here, no people with guns around us, no screams, and no wounded or dead bodies — but we were nonetheless deeply scared. We had no idea how we would connect with people and make a life here. Not being able to speak or understand the language was a huge problem. There were times when we thought we would go back to where we came from, no matter how hard it would be, because we didn't belong here. But we worked hard and converted our old style of living into a new one.

Today I'm an American citizen. I will forever be grateful to this country for the opportunities it has given me. I remember the kindness people showed us when we got here. We had a roof over our head, food on the table, medical help, clothing, bedding, furniture, and so much more. But I also remember the hatred some people felt toward me because I could not speak English properly.

My first school was Fanning Middle School. The school building didn’t look much different from the one I was used to, but on my first day I had no idea what to do or where to go. I had a schedule, but I couldn't read it. In my first class, the teacher pronounced my name so wrong, I felt embarrassed — I couldn’t even explain who I was and where I came from. Students were calling me names; some threw little balled up pieces of paper at me. That day I came home from school and told my parents that I was not going back to that school again. All I wanted was to go back to my country, to a place where I would fit in better.

My parents stayed positive and kept telling me that day by day it would get better. But it wasn't easy for them, either. Only two months after our arrival in St. Louis my mom started working, but she didn’t drive. Some friends explained how to use the public bus. The next morning mom took the bus and made it to work fine, but getting off work, she took the first bus to arrive without knowing which direction it was going. She rode for about fifteen minutes and started crying because nothing was familiar. After some time almost everyone had gotten off the bus but my mom was still sitting with watery eyes and a frightened face. The bus driver soon realized that the language was the problem and drove around for 40 minutes until mom recognized one familiar street. “I’m OK now, I found home, thank you,” she said, using her hands to try to explain. She walked for half a mile after that but at least she knew that she was near home.

St. Louis was one of the cities chosen to take refugees due to the availability of housing and low-paying jobs we were willing to do. Cleaning, taking trash out, dusting, lifting, carrying heavy objects, working overtime, having more than one job, we did it all. One Bosnian would get hired by a company and would bring in another and then another. Mouth by mouth, word spread and positions would fill fast. The ones who didn’t speak the language followed the ones that did — having another person who spoke their language in the same company was a blessing.

My father was hired in a company called Triad Manufacturing and worked for minimum wage. My mother got hired in a hotel downtown as a cleaning lady and also worked for minimum wage. They worked every day, but they couldn’t be promoted to supervisor because they didn’t speak English. Year by year, though, they worked their way up. Today south Saint Louis has a huge community with a variety of different professionals, all of whom came from Bosnia. From doctors to to lawyers to restaurant owners and travel agents — hard work does pay off at the end.

However, it seems this country, whose entire population is made of immigrants from all over the world, has forgotten her own history. People say hateful things like, "Don't let them in, they are taking our jobs, our money, and our country." Where is this hate coming from?

Just so we are clear on certain things: The U.S. government does not pay for a refugee flight to come to this country. Refugees pay for their own airfare. It's not a free ride. My family and I got a travel loan and had to start repaying it six months after our arrival.

Some people tell us that we need to go back to our country. Why? We cause no harm to others, and we have made this country our home. Our children were born here. There is a reason we were called refugees. Our country fell into war; there were no jobs or freedom. We were looking for a way out. A refuge.

Some of us have been here longer than we were in our birth country. Yet we Muslims are now afraid that we will be forced to leave this country where we built a new life. I have always been open about my religion, because it was never an issue. But with the new president and his heartless statements on Islam and immigration, I wonder: Will people use it against me? Will my friends think of me differently? How far will he push, and how far will people follow?

While I am a U.S. citizen, my parents and some of my friends are not. And all of a sudden people who have green cards and visa holders are frightened. They have been living in this country for years, they have jobs and families here, and they are now afraid to leave the country out of fear of not being able to return. I’m afraid that they will have to leave this country and leave behind everything they worked so hard for. Ever since the ban this became the main subject of conversation in my community. Some of my friends are even thinking they'll stop paying their loans in case they end up being deported.

Two weeks ago, when there was a protest at the airport, some of my relatives called me. People were there to tell others that not all Muslims are bad people. I'm proud of the people in St. Louis and across the country for standing up and practicing their right to "freedom of speech" and making their voices heard. Just watching it for five minutes was enough. I want to say a big "thank you" to those who cared enough to say that they are thinking of me and my family and that they still welcome me into their country.

Yet in the media people were commenting horrible things about immigrants and how they don’t belong in this country and that they should leave. It felt like a slap in the face.

Years ago when my parents decided to leave our birth country, I was afraid, not knowing where life would take me. I had to say goodbye to my relatives, including my grandma, who I had lived with for the first thirteen years of my life. We shared the last piece of bread at times. She watched me, she changed me, she fed me. Just before I boarded the bus as I was leaving to start my new life journey in the United States, my grandma said to me, "Honey, I lived life. Now it's your turn. This is it; we are not going to see each other anymore. I hope this new journey gives you a much happier life.”

I wiped her tears off, as she did mine. That hug was short but strong, and it was my last feeling of my grandma. We never saw each other again, just as she had said. That was hard. Now many years later I'm in the same position. My parents are frightened that they will have to leave this country. Do I or my kids say goodbye to them, or do we follow them to some other country, to start over again somewhere new? How do I tell my kids that they might have to leave their birthplace because of the rules the president made?

How far this will go we don't know. I do know that if my parents go, we go with the thought that if one door closes, another will open. For we did the same nineteen years ago when we immigrated to this country.

Sejla Grahovic lives in St. Louis. Her 2014 memoir, While You Played, I Ran is available on Amazon.