Larry Moreau and his family were cruising the Lake of the Ozarks on a sunny Saturday last May when they noticed a Missouri Highway Patrol boat race past them. Moreau, an engineer from nearby Jefferson City, recalls looking down at the speedometer on his boat and seeing that it read 32 mph. The patrol boat, containing a trooper and another man standing next to each other, was traveling much faster than that.

A few moments later the patrol boat came into view again. This time it was stopped in the middle of the lake's main channel. In front of the boat, a few hundred feet away, was something else.

"My wife said, 'There's somebody in the water.' It scared me something fierce, and I came to a complete stop," says Moreau.

A man's head was bobbing up and down in the wake. A few feet away from him floated a life jacket, and though the Moreaus couldn't see the swimmer's arms, he seemed to grab at the flotation device once or twice only to let it go. Moreau witnessed the trooper, now alone onboard the highway-patrol boat, "messing with his controls." Finally, the officer navigated the vessel back toward the man in the water. At one point the officer was close enough to touch the man, but as this happened, Moreau says, the trooper, Anthony Piercy, moved to the opposite side of the boat.

From their vantage point a few hundred feet away, the Moreaus started quizzing each other about what might be happening. It was dangerous to swim in the lake's main channel on such a busy day, but the trooper and the man looked oddly at ease — like friends enjoying an afternoon dip.

"[The trooper] didn't bend over or do anything" to grab the man, Moreau says, nor did the officer seem to panic or send emergency cues. "My son said, 'Dad, is this a training exercise?' My wife was like, 'No way. They wouldn't do that in the middle of the lake.'"

Another 30 seconds passed, and again the waves began carrying the boat away from the man. A party barge full of people soon arrived, and its occupants also took in the scene. The Moreaus, now convinced nothing was wrong, headed back to their marina.

As they pulled into their boat slip a few minutes later, another trooper was frantically jumping onto a patrol boat docked nearby. "Hey, one of your guys lost his passenger out there!" Moreau joked. The officer fired back: "That's not a passenger. That's a suspect, and he's gone."

That's when Moreau and his family realized what they saw. "My God, that person was handcuffed," he recalls saying.

Two hours later, at about 7:30 p.m., the Moreaus were still at the marina when the party barge returned. Its passengers confirmed their fears. The handcuffed man, who the Moreaus would later learn was twenty-year-old Brandon Ellingson, had continued to tread water for three more minutes. Eventually the trooper tried reaching out to Brandon with a pole. When that didn't work, he finally took off his firearm and holster, kicked off his shoes and dove in.

"Then they both went under, and the trooper came up alone," one of the party-barge passengers would later testify to highway-patrol officials. "The last words I heard from the victim were, 'Oh my God.'"

While listening to the passengers recount their story, Moreau noticed two young men in his peripheral vision. They approached and asked what everyone was discussing.

"I guess this kid drowned on a water-patrol boat," Moreau's wife, Paulette, told them. One of the two young men, Brandon's best friend, Brody Baumann, went pale and vomited.

Baumann isn't the only one who has become sick over the handcuffed drowning of Brandon Ellingson. Nine months later his death continues to torment the young man's family, friends and even complete strangers, such as Larry Moreau, all of whom want answers from a highway patrol that they believe has been less than forthcoming about the events of that day.

"The first mistake was killing him," says Brandon's father, Craig Ellingson, when discussing the Missouri Highway Patrol. "The second was trying to cover it up."

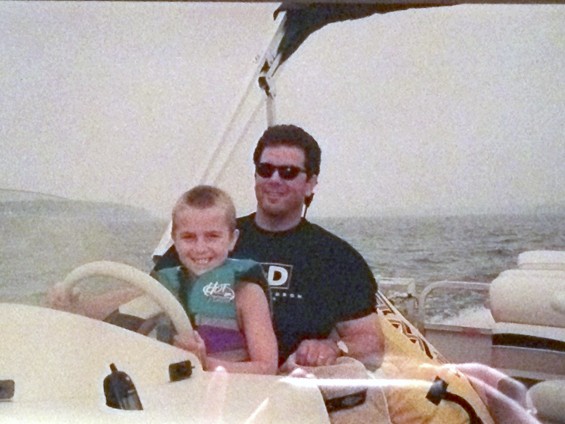

Brandon Ellingson grew up spending his summers at the Lake of the Ozarks. His parents, Craig and Sherry, bought a place near the lake's twelve-mile marker in 2002, and they regularly ferried Brandon and his younger sister, Jennifer, from their home in Iowa to their vacation property in mid-Missouri. On May 29 of last year, Brandon made that same journey with a group of seven childhood buddies.

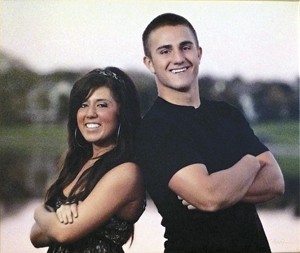

They were to spend the weekend reliving the good old days, and up until Brandon's run-in with trooper Anthony Piercy, the trip had gone as planned. Brandon, who was about to enter his junior year at Arizona State University, was the same Brandon his friends had come to know and love — the straight-A student, the buff athlete, the one who made everyone feel as though they belonged.

On Saturday the friends took the Ellingson family boat, a 28-foot Sea Ray playfully named Sotally Tober, to a restaurant and bar on the lake called Coconuts Caribbean Beach Bar & Grill. There the young men spent the sunny afternoon downing beers and buffalo wings and playing sand volleyball.

Around 5 p.m. the boys pushed away from Coconuts' dock on their way back to the Ellingsons' vacation home. Brandon "seemed fine," his friend Baumann remembers. "He told us, 'Clean up and sit down, and then we can take off.' Just normal Brandon." But before the boys had gotten out of the no-wake zone, officer Piercy pulled them over after allegedly witnessing a Bud Light can fall from the boat.

The Ellingsons' boat would be the third watercraft Piercy pulled over that afternoon in front of the popular Coconuts — much to the vexation of the restaurant's owner who had earlier called the highway patrol to complain of an officer "sitting there all day" and "harassing" people.

Once onboard the Ellingson boat, Piercy assured the boys that he just wanted to make sure everything was in order. A few minutes later, he brought Brandon onto his vessel and pushed about ten feet away to conduct a field sobriety test. Although the boys couldn't hear the words exchanged, they imagined their friend would fall into the stutter he'd had since childhood, which got especially pronounced when he was scared or excited.

One of the boys in the group, Myles Goertz, had a "know your rights" card in his pocket and tried to toss it to Brandon in the trooper's boat.

"That's when Piercy got pissed," Baumann says.

That's also when he got in a hurry, Piercy later told one of his superiors, Sergeant Randy Henry. Piercy handcuffed Brandon and wedged him into the wrong type of life jacket, even though the boat was also equipped with flotation devices for shackled suspects. He told the boys that he was going to take him to the patrol station across the lake for ticketing. Nick Buchanan, a childhood friend of Brandon's, estimates that the arrest lasted about five minutes. "He told us to meet him there, pay the fine and we could take him home," he says.

As he took off, Brandon turned back to his friends. He winked. "It was reassuring at the moment," Buchanan says. "It made us feel like everything was going to be OK."

But when two hours passed and Brandon's friends still hadn't heard from him, they began to worry. Back at the Ellingson family vacation home, the boys started calling around to local jails.

"They were like, 'We don't have a Brandon Ellingson booked,'" Buchanan remembers.

Then came the disturbing talk about a drowning that Baumann and Brandon's other friend, Louis Gutierrez, heard about at the marina where they'd gone to look for him. The friends were distraught when at 8:41 p.m. a state trooper arrived at the Ellingson house with different news. He pulled Brandon's cousin, Blake, into his car and said that "Brandon had gotten belligerent and he'd have to spend the night in jail," Buchanan remembers. "It was strange because Brandon wasn't that type of guy, but we were just so relieved that he was safe."

The relief didn't last long. Shortly before 10 p.m., Craig Ellingson, at home in Iowa, got a call from highway patrol. They told him that the boat capsized and Brandon drowned. Craig immediately called his son's friends. "Guys, what is going on? Where is Brandon?" he asked. "They're saying he drowned."

"We told him, 'No, Craig, that's not what happened. We're going to get him in the morning. We have the money to bail him out,'" Buchanan remembers.

A half hour later — at 10:28 p.m. — Buchanan's phone rang. "Is this Nick Buchanan?" The caller identified himself as some officer from somewhere. Buchanan forgot it all after the caller's next words. "I'm sorry to tell you this, but your buddy fell off the boat today and he drowned."

"I didn't say anything. Just hung up on him," Buchanan says. His face fell into his hands. The guys upstairs came rushing down, thinking what they were hearing was laughter, that Brandon had been found. But when they saw Buchanan's heaving shoulders, they knew.

After finally learning the truth about Brandon — some five hours after his drowning — the friends packed up their belongings and headed back to Iowa that night. Buchanan remembers looking in the rear-view mirror at the faces of his friends, shocked and silent.

Just two days earlier they'd traveled those same highways en route to the lake. Then, the ride was filled with laughter and music. Brandon loved a song called "Jubel" by the French house musician Klingande, and he played it on repeat, trying to convince his friends to love it, too.

The song has few lyrics. It's mostly a refrain of two words: "Save me."

The coroner's toxicology report showed Brandon's blood-alcohol content was more than three times the legal limit — 0.268 percent — and also detected the presence of .13 micrograms of cocaine in his body. Based on that, the Morgan County coroner, M.B. Jones, would go on to list the official cause of death as asphyxia due to drowning. "Contributing to the death is alcohol and cocaine use," noted the coroner.

In September, Jones assembled a jury for a coroner's inquest to determine whether the death was accidental or not. The Missouri Highway Patrol and officer Piercy declined interview requests for this article. But the patrol did present its investigation of Brandon's drowning during the inquest. Among its findings was that Brandon had purchased six beers and two shots during the hours they spent at Coconuts.

In a tearful testimony before the jury, Piercy said his boat was going about 10 mph when Brandon suddenly stood and "jumped or fell" overboard. Piercy said he grabbed the suspect's foot but it slipped through his hand, at which point he stopped, jumped in the water and grabbed Brandon, whose life jacket had already come off. Piercy admitted using the wrong type of jacket, saying he did so because he wasn't properly trained. Piercy said he exhausted himself trying to tread water, lost his grip and Brandon slipped under.

The driver of the party barge also testified at the inquest, saying he believed Piercy had done everything possible to try to save the man in the water. The jury deliberated for eight minutes before ruling Brandon's death accidental. Three days after the inquest Morgan County's special prosecutor, Amanda Grellner, announced that she also would press no criminal charges against Piercy.

But as Brandon's family and supporters have discovered, parts of Piercy's story changed between the time of the drowning and the coroner's inquest. Brandon's arrest was never caught on video, despite a camera aboard the patrol boat. In a recorded phone call to Sergeant Henry soon after Brandon's drowning, Piercy said he noticed earlier that day that the camera was missing its memory card. But at the inquest, Piercy testified he didn't notice this until after Brandon drowned.

Piercy also told Henry in that phone call that his own flotation device didn't inflate. Henry responded that the life belt doesn't inflate automatically but only when its ripcord is pulled. Piercy told the jury he tried unsuccessfully to grab the cord. Moreover, Piercy told his supervisor that Brandon was seated in the boat and not, as Larry Moreau and his family remember, standing next to the trooper.

Craig and Sherry Ellingson further argue that GPS data proves that the patrol boat was traveling much faster than 10 mph (as Piercy maintained at the inquest) when Brandon went overboard. They assert that some of the jurors — and the coroner himself — are friends with Piercy. And they note that the toxicology report the coroner presented at the inquest is the second version. The first one, performed by the highway patrol, indicated that Brandon had a somewhat lower BAC of 0.24 percent and made no mention of cocaine in his system. The second report with cocaine was only introduced to "drag Brandon's name through the mud," claims Craig Ellingson.

"I think we as a society want to believe that we can trust these types of things, that if we get into this situation it'll be fair. But this was completely set up to get the outcome they wanted," adds Sherry Ellingson. "It makes me wonder how often this happens."

Yet despite the outcry from Brandon's family, friends and others — the Kansas City Star called the process "infuriating" and "selective in the information released at the inquest" — Piercy was back patrolling the waters of the Lake of the Ozarks six days after Brandon's death.

Five years ago, Piercy would never have been on the water in the first place. In 2010 the Missouri Legislature passed a bill to merge highway and water patrol forces. The legislation was to save $3 million annually. In reality the merger has cost Missourians an additional $900,000 per year and, arguably, made the state's waterways less safe.

State-mandated hearings after Brandon's drowning uncovered that outgoing water-patrol officials left the highway patrol with four key training recommendations for its officers who'd now be patrolling state waterways. The highway patrol implemented only one of those recommendations, and among those it ignored was the swimming requirements the Missouri Water Patrol had used for decades. As a Star investigation revealed, Piercy — a heavyset 43-year-old who'd only worked land duties in his previous eighteen years with the patrol — received just two days of field training before starting his aquatic duties.

Henry's own testimony in those state hearings didn't speak well for his officer. Brandon's death involved "poor judgment" and "reckless" and "negligent operation," noted Henry, who chose to testify in street clothes as an individual and not in his uniform as a representative of the highway patrol.

Seated in his kitchen in Clive, Iowa, on a bleak December morning, Craig Ellingson speculates on Brandon's final minutes.

"I figure what happened is that Piercy slowed down to take wake. Brandon flew forward, hit his head and fell off the boat." As he says this, Craig puts his hand to his forehead, as if touching the face of his son.

Larry Moreau never considered himself one to question law enforcement. Prior to Brandon's drowning, he had always respected the highway patrol. He was friendly with the troopers stationed nearby at the marina, and last year he even worked an engineering project at the highway patrol's Jefferson City headquarters.

"I worked with them for months, with almost daily contact," Moreau says. "They're all professional people, and that's what has baffled me about the whole thing."

After discovering that Brandon was handcuffed, Piercy's actions took on a new light for the Moreau family. "The whole not doing anything started to look very peculiar, especially with a person without a life jacket and with handcuffs, it'd be imperative to do something quickly," Moreau says.

In the days after the drowning, Moreau and his wife emailed patrol officials to let them know they were witnesses, and although officials interviewed Larry and Paulette, their testimony wasn't allowed into the coroner's inquest. According to the highway patrol, the Moreaus' testimony didn't add any new information to the case. But the couple believes the patrol wanted to discount their side of the story from the start.

"They asked us to be brief," says Moreau of his initial interview with patrol officials. "They had little interest in details. They acted like they didn't need to know." After turning off the recorder, one of the troopers expressed to Moreau that in his opinion, "the kid put himself in that position by getting arrested."

Moreau couldn't believe it. "My response was, 'The officer didn't make any move to save that kid.' You can't say that just because someone made a mistake that thousands of people do, they deserve to die. That's ridiculous."

When Moreau later learned that neither his nor his wife's interview made it into the coroner's inquest, he launched his own investigation using the GPS data transmitted from Piercy's patrol boat. Poring over the minutiae of satellite signals, the engineer came to two brow-raising revelations. The first was that Brandon — who Piercy testified was drunk to a nearly incoherent state — treaded water while handcuffed in the choppy lake for four and a half minutes.

The second was the strange route that Piercy took in the middle of those minutes. According to the GPS data, Piercy's boat slowed abruptly from speeds above 40 mph to 6 mph — presumably when Brandon fell out of the boat. The boat then turned 90 degrees. Then it shifted back to the same direction it had been traveling previously and continued on several hundred feet away from a handcuffed Brandon in the water. The boat then finally stopped. That's when Moreau believes he came upon Piercy fiddling at the controls.

"If someone falls out of your boat, you'd think the response would be to slow down and turn 180 degrees to the right or left," posits Moreau. Instead, it seemed that Piercy drove away from Brandon at a crucial moment when he might have saved him. To help the public and the investigators understand the GPS data, Moreau made an illustrated video on his iPad.

And while he admits that he's not a GPS expert, the technology corroborates most of what he saw on the water last May. As he told investigators: "'Look, guys, I saw the beginning, and I know the end. But your version doesn't explain the middle. What happened in the middle?"

It's a question that Moreau and his wife have asked themselves countless times.

"I've got close family members who say we're crazy, just let it go," says Moreau. "But this kid got shortchanged. He lost his life. There's just something about seeing something like this and knowing the truth's not being told. That'd haunt me to the grave if I didn't speak out."

In December the Ellingsons filed a federal lawsuit accusing Piercy of violating Brandon's constitutional rights by failing to outfit him with a proper lifejacket and allowing him to drown. The suit also charges ten high-ranking members of highway patrol and the coroner with conspiring to cover up information during the investigation. A second lawsuit filed in state court accuses the highway patrol's custodian of records of withholding information.

The lawsuits are "not something we're looking forward to," Craig Ellingson says. "I just want them to see how dirty it is down there. The public is not safe."

In recent months, several big names have also joined the Ellingsons' cause. Iowa governor Terry Branstad and U.S. Senator Charles Grassley, a Republican from Iowa, have pushed the Department of Justice to open a federal investigation. And in response U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder promised to personally review the case.

There are signs, too, that much of the general public is as upset as Brandon's family and friends. Of the ten most popular editorials published last year in the Des Moines Register, three were about Brandon. More than 130,000 people have signed a Change.org petition Brandon's mom launched that asks for a "full investigation" into her son's "tragic death." And a Facebook page titled "Justice for Brandon Ellingson" has nearly 10,000 fans.

Social-media commentary ratcheted up again in November when the highway patrol released transcripts of its officers' phone conversations in the aftermath of the drowning. Piercy can be heard referring to Brandon as a "little bastard" and suggesting he purposefully jumped off the boat. In another conversation with a dispatcher, a patrol commander joked that he wouldn't risk sending divers to recover the body that night because Brandon would be "no more dead in the morning" and requested that the dispatcher withhold information from her report about Piercy's mistakes.

"To Missouri law enforcement, this was apparently a laughing matter. Outrageous," wrote one Twitter user. "This broke my heart but true colors of this tragedy are slowly emerging," came another tweet carrying the hashtag #JusticeforBrandonEllingson.

Meanwhile, Larry Moreau continues his quest to deliver that justice. In November he and Paulette invited Morgan County's Grellner to lunch, and he says she told them she would take another look at the case. Just last month highway patrol officials re-interviewed the Moreaus, though it didn't go much better than the first round.

"I felt like I was trying to talk my way out of criminal charges," says Moreau. "They insinuated that I was being paid by the Ellingsons to do this. I kept telling them, 'I didn't see what happened here. I just know the version you guys are telling doesn't add up.'"

Still, Moreau hopes those interviews — and similar ones he's given to the media and anyone willing to listen these past nine months — won't be in vain.

"There's so many more people that know the truth," Moreau says, sighing. "The people who should have this information now have it, and can act accordingly. It's a huge weight off your shoulders."

Postscript: Earlier this month Piercy's superior, Sergeant Randy Henry, left a note on the Facebook page "Justice for Brandon Ellingson" hinting that new details could emerge in the future. "My main focus is, and has been from day one, to let this young man rest in peace, to clear his name, and to let the Ellingson family know exactly what happened before, during, and after that horrendous day," wrote Henry. "There are people in my inner circle who have the same feelings that we all have, and who I believe will step up when it's time to."

Contact the author at [email protected].