This weekend marks the 100th anniversary of one of the most brutal and shameful episodes of mass violence in American history. Dubbed the East St. Louis "race riot," the events of July 2 and 3, 1917, tore East St. Louis apart and shocked the nation. The violence was largely one-sided, with mobs of armed whites burning hundreds of black homes and beating, lynching and shooting black residents. Most historians estimate that more than 100 people died.

This week's RFT cover story delves into the legacy of the violence — which some descendants characterize not as a riot, but as a war for survival.

Like any war, the events of those days in 1917 were heavily documented at the time, and many primary accounts are now available online. While the RFT cover story includes short excerpts from eyewitnesses and later investigations, there's no replacement for the original, full-length material.If you want to dig into what things looked like to those on the ground, Carlos Hurd is a good place to start. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch reporter authored a gripping, 3,000-word account published on the front page of the paper's July 3 edition.

Found on Newspapers.com

Hurd pulled no punches in describing the horror he saw on the street. This is how he opened the piece:

"For an hour and a half last evening I saw the massacre of helpless negroes at Broadway and Fourth Street, in downtown East St. Louis, where black skin was a death warrant."

In the story's conclusion, which can be read here, Hurd directly addressed the reports of an armed black militia firing on two plainclothes police detectives on July 1. Both officers were killed, though one had not yet succumbed to his wounds at the time of Hurd's July 3 piece. The officers' deaths — which eyewitnesses would later claim was accidental — were blamed for sparking a chain reaction of mob violence and indiscriminate murder over the next 48 hours.

Here's how Hurd ended his account:

"In recording this, I do not forget that a policeman — by all accounts a fine and capable policeman — was, killed by negroes the night before. I have not forgotten it in writing about the acts of the men in the street. Whether this crime excuses or palliates a massacre, which probably included none of the offenders, is something I will leave to apologists for last evening's occurrences, if there are any such, to explain."

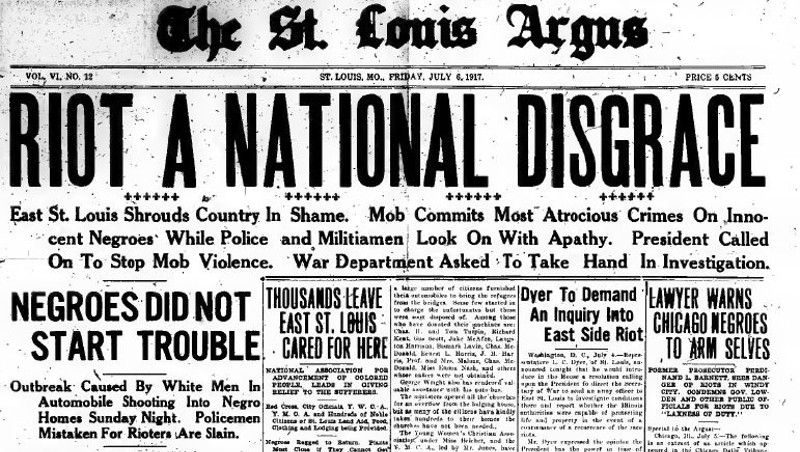

Days later, the St. Louis Argus, a black weekly, would publish its own investigation into the shooting of the police officers. Based on interviews with black residents, the paper concluded that the officers were not intentionally ambushed, but rather mistaken for a carload of white drive-by shooters who had previously attacked the neighborhood. The Argus' July 6, 1917, story can be read here.

The true scope of the horrors, however, did not reach the public until outsiders came to pick through the pieces. W.E.B. DuBois, an early civil rights leader and co-founder of the NAACP, traveled to East. St. Louis with suffragist/activist Martha Gruening. There they interviewed survivors and collected photographs documenting the destruction. Those pictures were a rare commodity, as police officers had been seen destroying journalists' cameras during the riots.

DuBois and Gruening's work was published in the September 1917 issue of the NACCP magazine The Crisis, and it offers a peerless and sweeping perspective on the weeks leading up to the explosion of violence. Notably, the piece includes a full-page reproduction of a May 23 letter sent by Edward F.

Mason, a union leader who inveighed against the influx of "undesirable negroes" and suggested that "drastic action must be taken if we intend to work and live peaceably in this community."

The Crisis 1917 by Danny Wicentowski on Scribd

The Crisis' expose also featured the lengthy first-hand accounts of victims and survivors, as well as photographs of their injuries — including an elderly woman with horrific burn scars on both arms and a 20-year-old whose arm had been shot off by soldiers and police officers. Additional first-hand accounts from survivors were collected by anti-lynching journalist Ida B. Wells.

The Crisis' story ended with a jarring, simple question: "And what of the Federal Government?"

Although President Woodrow Wilson initially opposed launching a federal investigation, Congress felt otherwise, in light of the fact that the massacre had disrupted wartime industry for more than a week and left hundreds of buildings destroyed. The congressional inquiry's final report was delivered July 6, 1918, and it can be read in full here, though you'll have to make sure you're on page 8,826 and scroll to the the middle of the right-hand column.

The report blasted East St. Louis' corrupt civil government, its incompetent police force and complicit militia members. Presenting a broad of range of competing explanations for the causes of the violence, the report concluded that while labor issues played a role, the underlying driver of the massacre was racial:

"The officers of the mills and factories placed the blame at the door of organized labor; but the overwhelming weight of testimony, to which is added the convictions of the committee, ascribes the mob spirit and its murderous manifestations to the bitter race feeling that had grown up between the whites and the blacks."

As for contemporary accounts, 2008's Never Been a Time: The 1917 Race Riot That Sparked the Civil Rights Movement is essential reading. Author Harper Barnes is a former Post-Dispatch editor and a respected journalist. Barnes managed to fit an enormous amount of history into a compelling, hyper-detailed narrative that flows from the Great Migration to the present-day struggles of East St. Louis.

On the academic side, Pennsylvania State University professor Charles Lumpkins' book, American Pogrom: The East St. Louis Race Riot and Black Politics, intentionally sets out reframe the designation of a "race riot." Lumpkins focuses on the political causes behind the massacre, particularly efforts by the city's corrupt white political class to break the influence of the growing black community.

Finally, while no survivors of the summer of 1917 are left alive today, the words of some were preserved in the 1998 documentary "Bloody Island: The Race Riots of 1917." Directed and written by East St. Louis native Thomas Gibson, the film is free to watch on YouTube.

The area continues to reckon with the deadly events. This Sunday, July 2, a "Day of Reconciliation" ceremony will begin at 11 am at Truelight Baptist Church (1535 Tudor Avenue, East St. Louis). Additional events to commemorate the hundredth anniversary are planned for this weekend and throughout the rest of July, and a full schedule can be found at www.estl1917ccci.org.

Follow Danny Wicentowski on Twitter at @D_Towski. E-mail the author at [email protected]