History can accumulate when we're not looking: a pack of matches from a bar that closed decades ago, sheet music from the cheeky songs we sang, the seemingly "boring" paperwork that implies so much more than it actually states.

Steven Brawley thinks so, anyway.

Brawley, 45, is a history buff and a blogger — and his blogs, not surprisingly, incorporate both his love for the past and his identity as a gay man in St. Louis. He's been detailing his obsession with Jackie O at www.pinkpillbox.com for years.

And Brawley's one-year-old blog, www.stlouisgayhistory.com, is the Internet repository of his latest passion: documenting the history of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender life in St. Louis. He's gathering artifacts and mementos from the people who lived it, publishing online a history that mostly happened outside the books.

"Scrapbooks, postcards, anything. We're looking to document daily life," he says. "What was life like? Where would you go to socialize? Where did you go? Wink, wink, special knock?"

We've come a long way from the days when cross-dressers could be arrested in St. Louis, as many were under a municipal ordinance enacted in 1864 and not repealed until 1986.

Or be targeted in one of the 1960s undercover operations meant to catch men engaging in anonymous "tea room" sex.

Or find your name, address and occupation published in both the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and the (now departed) St. Louis Globe-Democrat after a sting in Shaw Park — as happened to some gay men as recently as 1984.

These days, gays and lesbians enjoy increased acceptance in mainstream culture. In Illinois, same-sex couples have the right to marry. And while that's still not true on the Missouri side of the river, the St. Louis Pride celebration — which kicks off this weekend — is widely regarded as the largest in the Midwest. Last year's event drew 80,000 attendees.

"A lot of younger folks feel privileged," Brawley says, even as "there were these struggles to allow them to live a different life."

If that's forgotten, he believes, something crucial is lost.

Brawley's blog isn't the first attempt to preserve St. Louis' queer legacy. The State Historical Society Research Center-St. Louis, at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, has maintained archives of all sorts of Missouri history, from the suffragette movement to the construction of the Gateway Arch to, yes, the culture (and persecution) of the city's gays and lesbians.

Curated by genial history nerd William "Zelli" Fischetti, the UMSL archive is a hidden gem. The boxes and folders are filled with memorabilia stretching back to the '60s. Find early informational pamphlets on a mysterious, scary disease that came to be known as AIDS. Browse lesbian magazines with car-maintenance tips so liberated women could maintain their vehicles without the help of any man. Check out pins and T-shirts from year after year of Pride events.

But while the UMSL archives of lesbian and gay history are fascinating and comprehensive, they're not terribly accessible, tucked away as they are on the bottom floor of a campus library. And because none of the materials can be checked out, it's an effort to absorb it all.

Enter Brawley. Along with Colin Murphy, senior writer at the Vital Voice, St. Louis' gay magazine, he's been working both to digitize the UMSL archives and collect more items, too. "We wanted to make as much of our stuff digitally available so people can look at it on their home computers," Murphy says.

On his blog, Brawley has been attempting to put together a comprehensive timeline of local LGBT history. Through parties known as Treasure Drives, he's been collecting whatever he can from local members of the community, documenting it and then turning it over to the UMSL archive. He's also recording oral histories for preservation.

Some history has already been lost. "When elder folks died, their families threw it out, some innocently, some not," Brawley says. "Some families destroyed it because they were ashamed."

But since Brawley started researching lesbian and gay history three years ago and launched a Web presence one year ago, the St. Louis LGBT History Project has found great success.

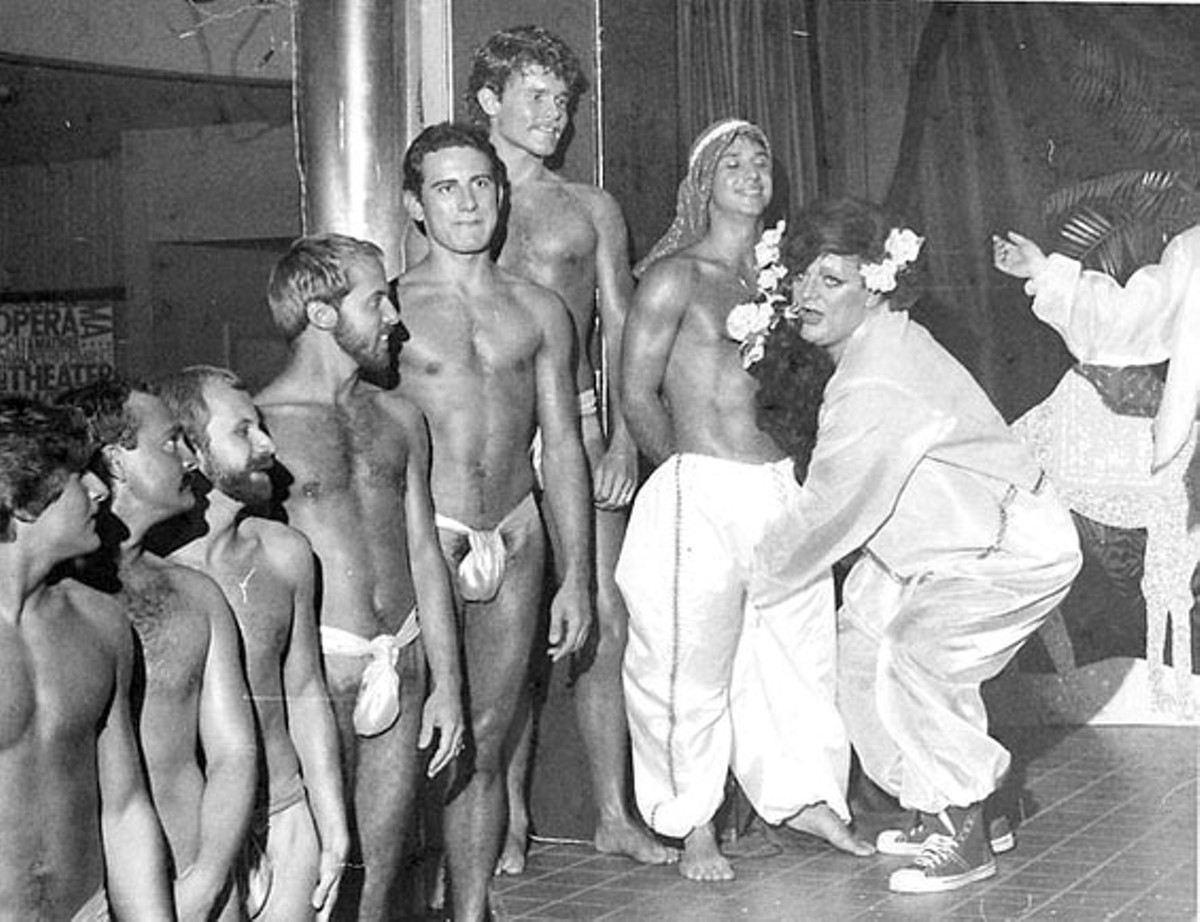

To date, two Treasure Drives have yielded photos of Halloween parties, bar ads and snapshots from drag shows from as far back as the 1930s. And Brawley's timeline now goes back to 1804, when a member of the Lewis and Clark expedition observed that among the Minataree tribe, boys who presented as girls were tolerated and accepted.

Inspired by Brawley's work, Riverfront Times sought out people who've contributed to the project and the city's sometimes hidden, but always thriving, gay culture. Movers, shakers and ruckus-makers alike had a few tales to tell.

Today, it's history. But at the time, it was, simply, life.

Margaret Johnson

At 70, Margaret Johnson has a lifetime of lesbian, feminist activism to look back on. She made history earlier this month — and the Daily RFT — for being among the very first couples in University City to take advantage of its new domestic-partnership registry.

As recently as eight years ago, though, one of Johnson's aunts encouraged her to fight the other "single" ladies for her niece's wedding bouquet — even though Johnson and her partner had been together for more than a decade.

Sitting in Meshuggah Coffeehouse in the Loop, Johnson has a quick smile and a steely silver crop. She's quick to distribute one of a stack of handbills she's brought advertising this year's Michigan Womyn's Music Festival, a feminist institution she's been a part of since 1979.

"I didn't become a lesbian till I was, like, 28," Johnson says. "We just called ourselves gays. We didn't have the word 'lesbian' yet."

A women's dance at Washington University changed her perspective.

"That was when I discovered a really different community. They were all political in a way I wasn't. They were lesbians — not gay! The incredible feeling of dancing, of being on a dance floor and looking around and realizing everyone's a lesbian, just knowing there's nobody here judging you. It's an energy you can't get anywhere else."

Johnson grew up in Des Moines, Iowa, and came to St. Louis to teach mathematics at Meramec College in 1964.

"Talk about being in the closet!" she says. Her colleagues knew she lived with a woman, but nobody understood that when they broke up, and that woman moved out, she needed the same support as a divorcing male colleague.

Gender roles were rigid, even for the faculty president.

"I never dressed the way I did at school anywhere else. Skirts, dresses, little heely things I hated," she recalls. It was a female fashion teacher in a chic pantsuit who unintentionally smashed that barrier: "In the late '60s, women just started wearing pants."

Teaching was Johnson's profession, but activism has always been her passion. Evidence of her work runs through the UMSL archives. There are articles she penned as "Flowing Margaret Johnson" in LesTalk, an early lesbian magazine that featured everything from financial advice to party advertisements. There's a folder filled with pink fliers for a "Stop the Church" protest, from April 19, 1992, which Johnson attended as part of St. Louis Queer Nation. The flier called it "a non-violent, legal action to draw public attention to the Catholic church's policies of oppression," in the areas of homosexuality, AIDS and reproductive rights.

The group's longest action, however, was against Cracker Barrel.

In 1991, Cheryl Summerville, a cook at an Atlanta, Georgia, Cracker Barrel was fired. Summerville's separation notice from the Georgia Department of Labor, part of a lengthy file in the UMSL archive, gives the reason why.

"This employee is being terminated due to violation of company policy. The employee is gay," it reads.

And so on Sundays, Johnson's group would go to the local Cracker Barrel — sometimes, there'd be as many as 50 people.

"We'd get coffee and wait till everyone was seated," Johnson says. "We'd get coffee and put a five-dollar bill on the table and say, 'This is your tip. We're not going to order anything.'" Then they'd hang out until the cops came.

After taking a beating in the press all over the country, Cracker Barrel changed its tune, overturning the company's prohibition on homosexual employees.

Speaking of tunes, Queer Nation serenaded the home of St. Louis Mayor Freeman Bosley Jr. at Christmastime in 1993.

The sight of a group of folks gathering on the lawn gave the Bosley family pause. When the carolers gathered in front of his house, she recalls, the Bosleys "turned the lights off, because they assumed it was an action." Then they heard the carols, popped the lights back on, and came out to listen.

And then they heard the group singing cheerily to the tune of "Good King Wenceslas":

We're your queer constituents

From the Queer Nation.

We pay taxes and cast votes

For your information.

Here's a thought you'd better heed

For this Yuletide season.

If next term you're unemployed

We might be the reason.

Richard Trennepohl

In his south-city home with his rickety old cat, Skinny, and a plate of elegant cookies for a guest, Richard Trennepohl, 58, looks back on the bad old days of elementary school, dressing hair for fancy west-county ladies and the bad-ass party scene that once thrived in the city.

"The apartment building I lived in had so many queers in it they called it Lavender Abbey," he says of the block of Maryland in the Central West End that he used to call home. "It was all the gay guys and a bunch of little old ladies, which was fun. Someone would pop up to see if you wanted to come for coffee."

In those days in the '70s and early '80s, he says, the neighborhood was called the "gay ghetto." Just mentioning the neighborhood might be enough to start a conversation: "I recall there was a time if you said you lived in the Central West End, people just assumed you were gay."

Both the Delmar Loop and the Shaw neighborhood's Magnolia Avenue were also considered gay parts of town. Indeed, it was for Magnolia Avenue that the Magnolia Committee, which launched the first Gay and Lesbian Pride Celebration in 1980, was named.

"It was a different crowd, different interactions probably. I was out every night — that was my thing. That was it back then — the bar."

He loved Clemetine's, NITES, Loading Zone. Back then, you couldn't just Google your way into bars like that, of course: "You found them through word of mouth, one of the bar rags — the newspapers. We've always had them."

The best bar, he says, was the old Herbie's, located at Euclid and Maryland avenues, just a few blocks from its current location. Steven Brawley has devoted an entire section to the place on his blog; it would appear that Studio 54 had nothing on the spot.

"Herbie's was really, to me, what I imagine a dance club in New York would have been like," Trennepohl says. "It had an eclectic group of people: heteros, females, high-energy music. It was upscale. I really hated the fact that it closed."

Even the cops, it seemed, respected the neighborhood's gay flavor.

One night, Trennepohl and some friends were out carousing in the West End at the Potpourri, which he claims was "notorious" for serving minors. The police came and asked for identification, so Trennepohl and his friends — all legal, mind you — decided to split for Herbie's.

A police officer informed Trennepohl that they shouldn't be carrying their drinks outside. Trennepohl insisted it was OK. But he couldn't help telling the officer, "You are so cute."

And, on impulse, he recalls, "I just reached out and kissed him." The officer's reply? "Uh, thanks."

While Trennepohl insists he has been on the sidelines politically, he's long been a member of the Metropolitan Community Church of Greater St. Louis, or MCC. A church pamphlet from 1973, preserved in the UMSL archive, describes the congregation as "open to all people but with a special ministry to the gay community."

He has also been involved with the Pride event since its 1980 beginning: "It was public, but I still remember early on people wearing big hats and sunglasses so they wouldn't be recognized in case there were news cameras there."

He speaks reverently of Lisa Wagaman, who died in 2009 and whose collected papers are in the UMSL archive.

"We lost a great pioneer in Lisa Wagaman. She was the individual that had a vanity license plate that spelled out 'DYKE.' She also was sort of a guard in Forest Park to ward off fag bashers. She was a transwoman and a big part of MCC. She was an integral part of gay St. Louis, in my eyes."

Erise Williams

Erise Williams remembers a time in the late '80s when the only prevention message that gay black men were getting about HIV and AIDS was to avoid having sex with white men, since it was supposedly a white man's disease.

"Most prevention messages were aimed at white men. It was foolish and naïve," he says.

Then came Virgil Grandberry.

Today, sitting in his office in Fairground Park, surrounded by images of Malcolm X and Spiderman, Williams reflects on Grandberry's work — and his own efforts to change such wrong-headed thinking.

Through his nonprofit, Blacks Assisting Blacks Against AIDS, better known as BABAA, Grandberry sought to get black men talking to their peers about the reality of HIV and AIDS. Grandberry thought Williams was just the man to take the prevention message out of their boardroom and into the clubs — and, in 1991, hired him to do just that.

In 1992, Grandberry himself died of AIDS. A BABAA newsletter from the time, which Williams has at his desk, contains Williams' touching elegy, which calls Grandberry "a treasure of a man." (Contemporary copies are also preserved at the UMSL archive.)

Williams tried to continue Grandberry's work. "I knew what we were doing was important," he says.

Williams' passion for the clubs was a huge help in getting the message out. His own introduction to the club scene happened when he was fifteen — but please, don't tell his mother that. (And anyway, he promises, the woman who took your money at the door would never let him leave with anyone sketchy or stay past 1 a.m.)

"I thank God for the Zebra Lounge! It's etched in my mind. When I'm 80, I'll still be thinking about the Zebra Lounge," he says. The Midtown club closed in 1989. "The beats! It was electrifying. This was black gay men comfortable in their own skin in a safe space. It was something to behold."

That safe space eventually became a key battleground in Williams' efforts to combat ignorance about HIV and AIDS.

"One of the silver linings behind the AIDS epidemic is it brought the community together. It brought the black gay community together. I met brothers who never told anybody about their status or met other positive people. In '94, we had the first support group for black gay men. It took off like wildfire."

But, as the face of AIDS has changed and new drugs have kept its victims healthier longer, that wildfire is dimming.

"We used to have the St. Louis AIDS Walk. It was primarily supported by white gays and lesbians and businesses," he says. "Involvement started to downturn because we were having African Americans and Latinos involved. People didn't see the need to give because it wasn't their people. We could not give up; we could have that force and passion."

Part of the BABAA's outreach was an annual party, the B-Boy Blues Festival, which started in 1995. It was a weekend of partying in the park and conveying the message of prevention and treatment for HIV and AIDS.

Out of this party arose another of Williams' contributions to the St. Louis LGBT community: Black Pride. A woman on the party committee saw the energy in the park parties and asked why there wasn't a black-pride event.

Soon enough, in 1999, there was.

"People get excited about Black Pride!" Williams says. "White people have said to me, 'Why do you have Black Pride?' It's not about being separate. We're not monolithic; we're diverse. There are some unique things that take place in both communities."

The two festivals have coexisted for years, and have been increasingly working to boost each other. This year, Williams turned over leadership of Black Pride; events leading up to that the festival have been going all spring.

"It's been a wonderful ride," he says.

Pam Schneider

Pam Schneider, 56, is happy to talk about her time as an LGBT media mogul in St. Louis, but if someone calls about a house she's got on the market, hang on. She's worked as a nurse, publisher and Realtor — Schneider's life, she says, has always been about taking care of things. She also spent nearly ten years publishing the Vital Voice, before turning it over to its current publisher, Darin Slyman, in 2009.

Schneider got into journalism almost by accident. In 1996, frustrated with nursing and not yet ready to leap full-time into real estate, she bought the Pride Pages, the LGBT business directory, her first foray into publishing.

"In my travels, I would see meaty papers for the alternative community, strictly LGBT papers. I'd come back here and see our little bulletin. I didn't know how to do a paper, nor was I interested in starting one."

And yet...

In 1999, Jim Thomas closed down his paper, the Lesbian and Gay News Telegraph.

"He didn't have anything to sell," she says. "I had to negotiate — he'd work with me for a year as my editor. In June 2000, we printed the first issues of Vital Voice."

Copies of the full-color broadsheet, headlined with Schneider's publisher's notes, are stored at the UMSL archive.

"When I first took on doing a newspaper, most people thought of publications for the gay community as rags — salacious, with so much skin. It looked like all you do is have sex and drink."

Indeed, even a 1986 pamphlet for Dignity St. Louis, a group for Catholic gays, featured burly fellas in bathhouse ads. Sex sells, of course, and every publication relies on advertising dollars.

But Schneider put her foot down.

"I would not do it. I turned down a whole revenue stream," she says. "Over ten years, I think it started to make a difference. The only place for distribution for magazines with skin was the bars. It would make me silently proud when you'd walk into a coffeeshop and see them reading the Vital Voice."

There was still blowback from the community.

"At the onset of me starting Vital Voice, most things in St. Louis had been by and large done by men. When I started the newspaper and called it the Vital Voice, it didn't take long until word got back to me that people were calling it the 'Vagina Voice.'"

But readership surveys, she says, indicated more men than women were picking it up: "They got over it being the 'Vagina Voice,' I suspect."

She still had to fight to get the paper distributed. Getting the paper into St. Louis Lambert International Airport in 2007 was one of her biggest coups.

She didn't always succeed.

"I wanted one of the boxes in Schnucks," she says. "They said we were too controversial. No skin, no sex ads, no dating services? What's controversial?" They never did get in.

Society has come a long way, Schneider says. In the early 2000s, gays and lesbians became so much more visible, with cultural touchstones like Ellen DeGeneres and Will & Grace coming onto the scene. Suddenly, there was a cultural cachet attached to being gay.

The Voice helped demystify the community in St. Louis by running prosaic profiles of people who'd come out, she says.

"This community spent time as the bogeyman. This put a face to it."

Kris Kleindienst

Kris Kleindienst was out and proud in high school, back in University City in 1970. Her mom was also a lesbian, she says, but never came out. Not after she divorced, and not even after a woman moved into her bedroom.

"It was a very different experience for her," Kleindienst says today.

If you're a book nerd of any orientation, it's likely you know Kleindienst, 58; she's co-owner of Left Bank Books. And it was a book, Kleindienst says, that helped radicalize her, bring her out of her shell and prepare her for a life as a lesbian feminist activist.

"In high school I waited tables in the Delmar Loop. A grad-student waitress gave me Sisterhood Is Powerful, and everything fell into place for me intellectually. I came out in this context of politics and feminism."

She started going to Gay Liberation meetings at Duff's in the Central West End in high school and quickly became aware of a burgeoning protest movement at Washington University. (While it was mostly antiwar, feminist and anti-racist activism was taking place there, too.)

Right after high school, she started working at Left Bank and got involved with a women's collective.

"We were the women's house. It was a euphemism — you never said 'lesbian,' you said 'women.' It sort of protected you out there," she says. The house was in the 4300 block of McPherson Avenue, before that part of the Central West End was gentrified.

"We decided women needed places to gather besides bars. Bars are associated with hooking up — we needed a place to talk politics," she says.

It was a big change at first for women used to the bar scene, but everyone adjusted.

"Eventually, our coffeehouse moved out of our house and into an apartment in south city," she says. But the place came to an early demise when it was firebombed.

Indeed, a 1979 clipping from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, preserved in the archive, notes an arrest following a fire at the Mor or Les bar on South Grand. The article notes it had "a reputation as a gathering place for lesbians." It also mentions that "a women's coffee house near Louisiana Avenue and Miami Street in south St. Louis had been open only about six months before it was firebombed in 1974."

"There was a lot of looking the other way," she says. "Women's spaces were firebombed in the '70s."

Around the same time, a friend from high school telephoned Kleindienst, looking for help setting up a show in St. Louis. The artist was Meg Christian, whose 1974 record, I Know You Know, is widely considered one of the first albums of "women's music."

Thus began Tomato Productions, a women-centered music production company Kleindienst and her friends ran for five or six years out of Wash. U.

"These concerts were places women came. It was transformational. They spent an evening being OK, having their love celebrated instead of dismissed," she says. "We had a lot of people tell us how much it meant to them. Culture is the best way to reach people."

Running and volleyball are also pretty good ways, as Kleindienst learned.

Kleindienst was part of the St. Louis contingent at the first-ever Gay Games in San Francisco in 1981, a gay- and lesbian-sporting festival modeled after the Olympics.

"To actively be celebrating us was unreal," she says. An article she penned a decade after first participating in Gay Games appears in the 1991 Pride Guide and clearly displays a sense of the energy that she and other athletes took back with them to St. Louis.

"You come back a real evangelist. Some people didn't understand the big deal about a bunch of gay people playing volleyball," she says. "To do something in a teamwork setting — there's an element of social health."

Rudy Nickens

If you wanted tofu in the Midwest in the mid-'70s, well, good luck with that. But if you did manage to find your way to the Sunshine Inn in 1974, you probably enjoyed Rudy Nickens' smiling face.

The Central West End vegetarian café opened in 1972. Until its 1998 closure, the place served as a community hub.

Now 56, Nickens will eat seafood and his mother's Thanksgiving turkey, though other than that, he's a veggie lover himself. But there was more to his interest in the café than food.

"I walked in and knew I wanted to be a part of it," Nickens says.

He was twenty, and he'd moved to St. Louis from his native Washington, D.C., to attend Wash. U. It was two years after the Sunshine Inn, a collective, had opened, and Nickens was quickly tapped to run the place.

"We were just a bunch of free-thinking, interested visionaries. Some call them hippies — I call them smart people," he says. In a business known for employee turnover, the Sunshine was unique: "The core staff was there for twenty years."

Campaigns and movements were launched out of the space. The city's first black mayor, Freeman Bosley Jr., held fundraisers there. Lectures on soybeans and the world food crisis fascinated Nickens and his customers. Author Frances Moore spoke about her vegetarian call to arms, Diet for a Small Planet.

"We had Buckminster Fuller — we made his last birthday cake. It was a carrot cake, and we tried to shape it like a geodesic dome," Nickens recalls. "The National Coalition of Black Lesbians and Gays had a national meeting there in 1987. It was important. It was important, and now it is history."

Nickens' memories of the community he helped build make him nostalgic. His co-owner was a straight white woman, and Nickens allows that they might never have developed the close relationship they did without the café.

"For a long time, 'vegetarian' meant 'lesbian,'" Nickens explains — a cultural shibboleth in much the same way that mention of the Central West End neighborhood was. "It was the lesbian influence on our culture. I was part of a very woman-centered organization for much of my life."

It didn't last. The financial reality of trying to run a left-of-center business ultimately did the Sunshine in, Nickens says.

He's had a string of corporate jobs, including his current one as the equal opportunity and diversity director for the Missouri Department of Transportation. "I went from an apron and Birkenstocks to a suit and tie overnight," he says.

Looking back, Nickens is saddened by the generation of gay men lost to AIDS: "Being 56 and a black gay man, I was in the demographic of people hit hardest by AIDS. I went to hundreds of funerals." Of the crowd he ran with before AIDS hit 30 years ago, he estimates, there might be five men left.

He's still an optimist.

"I'm the luckiest guy at the party," he says.