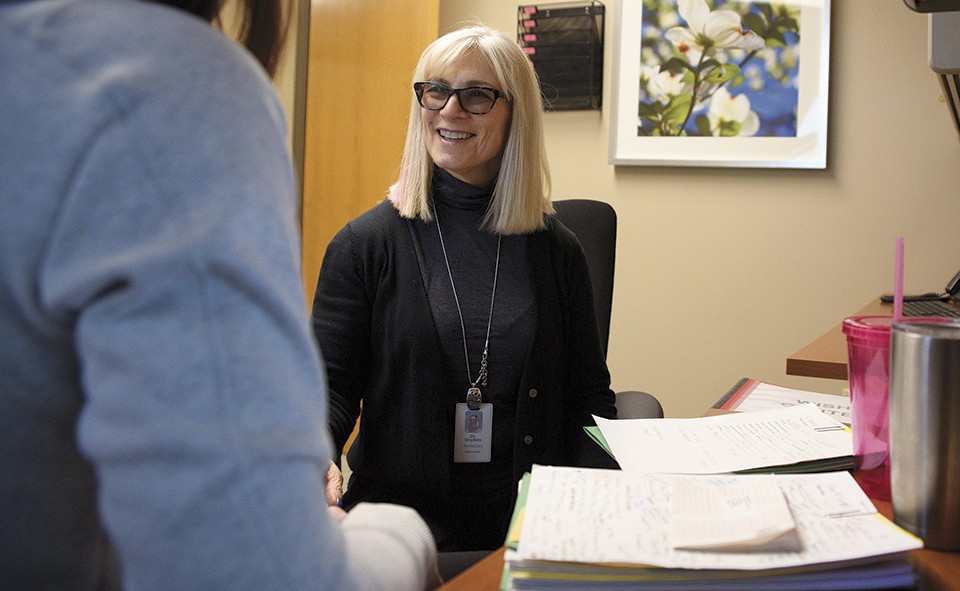

Dr. Jaye Shyken, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at SSM Health St. Mary's Hospital in Richmond Heights, leads the way. Shyken, the medical director of the hospital's Women and Infant Substance Help Center, known as the WISH Center, is a busy woman these days.

The St. Louis region is one of the hardest hit in the nation's raging opioid epidemic. Opioids comprise a class of highly addictive narcotics that include powerful painkillers like OxyContin and illegal drugs such as heroin and fentanyl, a synthetic form of morphine that is up to 100 times more powerful than heroin. Shyken's practice deals exclusively with pregnant women, new moms and newborns either addicted to opioids or enduring the symptoms of withdrawal.

Time can feel like a precious resource when you're one of the only physicians in the nation specializing in the combination of opioids and prenatal care. But on this Friday morning right before Christmas, Shyken seems happy to give the Clemens all the time they need.

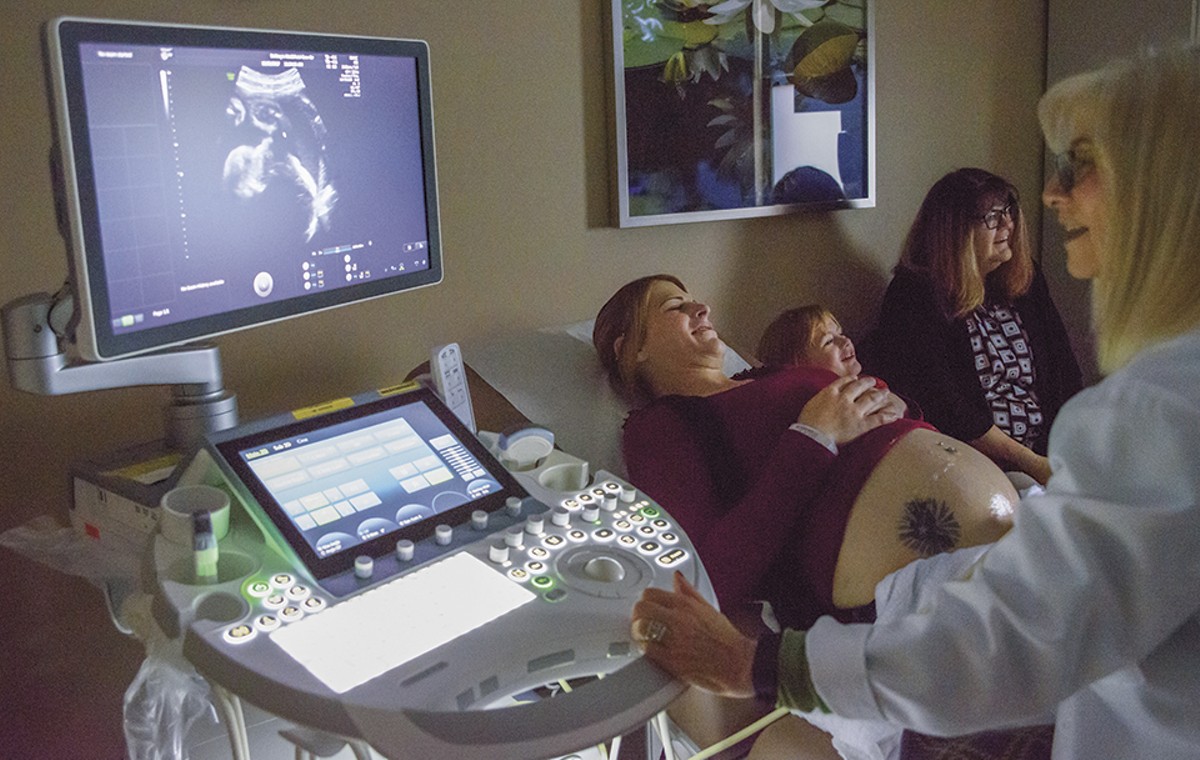

Rio, who is six months pregnant with her second child, is about to begin her latest ultrasound test. For Kylie, the next minutes will mark the first time she sees her new sister.

Rio sits on a bed, swings her legs up and stretches out. Shyken pulls up her shirt. Then the physician starts rolling what looks like a plastic wand across Rio's swollen belly.

All eyes focus on a large TV monitor mounted on the far wall. Shadowy smudges and blobs give way to the outline of an arm, a foot, the contours of a tiny skull. A heart, at first barely perceptible, flutters like the wings of a moth.

"I'm so excited, Mommy," Kylie says. "Oh, I see her."

"There you go," Shyken says, pointing to a moving blur on the TV monitor.

"Whooooa," Kylie says.

"They didn't have all this when I was having kids," Linda says.

Shyken points out the baby's bottom, heart and chest. "And right here, over the cervix, is the sort of behind," the doctor says. "The baby is sort of crossways right now."

That's not a problem; Rio isn't due 'til mid-March, and the baby should have plenty of time to right herself. Overall, Rio says, things are going well. "I don't get sick anymore," she says. "I keep things down. It's good."

She glances up at the monitor one more time.

"And the baby's face is up, so it's a little harder to see," Shyken says.

"She's always so low, it's like she's trying to find her way out," Rio says, laughing.

For Rio Clemens, the past months seem almost surreal.

Clemens has struggled for about a decade with an addiction to prescription painkillers and heroin. After serving nearly a year in a Missouri women's prison on a drug-possession charge, she returned to her hometown of Festus, about 35 miles south of St. Louis.

Once back in Festus, Clemens started using drugs again. And then, just weeks later, she learned that she and her boyfriend were going to have a baby.

Clemens did not know what to do. Neither did her regular OB-GYN.

"When I told my doctor what was going on with me, I mean, she almost looked like a deer in the headlights," Clemens recalls. "Like, 'What do I do with you?'"

Luckily, her physician knew about the WISH Center and Dr. Shyken, and sent Clemens there for the specialized help she would need. Shyken immediately placed Clemens on a drug called Subutex, which is also known generically as buprenorphine, to begin weaning her off opiates.

Shyken's goal is to get her pregnant patients on Subutex as soon as possible to reduce the risk of their newborns going through Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome, or NAS, a condition that results from exposure to drugs in the mother's system. Its symptoms include respiratory and feeding problems, jaundice and seizures.

Subutex belongs to a class of drugs known as opiate agonists. Like heroin and other morphine-derived narcotics, buprenorphine contains chemicals that cling to opioid receptors in the brain, reducing pain and triggering feelings of well-being. The drug helps keep at bay the cravings that push recovering opiate users into relapse; Clemens also began an intensive program of almost daily counseling and group programs.

The WISH Center has been a literal lifesaver, she says.

"I think a lot of people stereotype drug-addict moms who get help," she says. "They look down upon them, that their child is born addicted to something."

As the nation's opioid crisis worsens with no letup on the horizon, it has led to record numbers of babies suffering from NAS.

Every 22 minutes, on average, a child is born in the United States with NAS. An estimated 24,000 babies — a five-fold increase since 2000 — were born in the U.S. in 2013 with the syndrome, according to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Meanwhile, the number of overdose deaths continues to set new records, with almost 64,000 Americans dying from drug overdoses in 2016, though many experts think the true number is much higher. At least 250 people in St. Louis alone died that year from opioid overdoses — also a record.

In large part because of overdose deaths linked to the opioid crisis, life expectancy in the U.S. has fallen for the second year in a row, the first time it's dropped for two consecutive years in more than half a century according to figures released in December by the CDC.

The WISH Center is the only place of its kind nationwide. No other program does the work it does — providing detox services for pregnant women while helping them through pregnancy and caring for their babies afterward. As such, it serves as a template for similar programs being set up in other cities.

The WISH Center officially began as a full-time, freestanding facility fifteen months ago. Today it serves an average of 120 patients per week and employs a staff of twelve full-time workers or their equivalents, including nurse practitioners and pharmacists. It offers the equipment, trained staff and resources to provide prenatal care, substance-abuse treatment and relapse-prevention help for up to two years after birth.

The center, which is led by SLU maternal-fetal medicine physicians, also provides financial counselors to help patients apply for Medicaid, the federally funded health-insurance program for low-income families, and it connects them to social-service programs to provide job training and other aid, according to Donna Spears, SSM Health's director of maternal services.

"Because the goal is to keep mom in sobriety into the next pregnancy, hopefully for a lifetime," Spears says. "That's why we had to engage with organizations that really have more experience and resources in that area."

Shyken came up with the idea for the WISH Center more than three years ago. At the time, it was just a half-day-a-week pilot project.

"And it was pretty clear that we were way over-subscribed," she says. "We didn't do any advertising. Just taking existing people and using word of mouth."

The board at SSM Health St. Mary's soon bought into Shyken's vision and made a $1.2 million capital investment, locating the facility in a nearby medical office building in Richmond Heights. A satellite is set to open in Carbondale, Illinois, by April 1.

For St. Mary's, the decision to open the WISH Center was straightforward, says Spears. Still, she knows the type of medicine the WISH Center practices is not easy, which helps account for the dearth of competitors.

"Many folks don't exactly want to take this on," Spears says.

Of patients, she adds, "They have many other conditions related to their illicit substance abuse. And a lot of physicians don't have the training or the time needed to work through all the different social aspects and all the things that go along with training these patients."

Women with opiate addictions sometimes present with infections in their blood or skin abscesses from using dirty needles to inject drugs, Shyken says. And often her patients need antibiotics for long periods of time.

"This is not a population you can send home with an IV to get home antibiotics," Shyken says. "Not going to send an IV drug user out with an IV. So they're sort of in the hospital for six weeks."

Underlying mental-health conditions, such as depression, severe anxiety or dealing with the aftereffects of childhood abuse — conditions that might have contributed to patients abusing opiates in the first place — can also present a complication.

"We know drug use associated with anxiety and depression and hopelessness that just comes as a result of the changes in their lives because they're using drugs," Shyken says. "But some of this occurred before their drug use, and the drug use is really self-medication, and their best chance of prolonged sobriety is going to be treatment of both."

Still, a central part of the WISH Center's vision is to make its patients feel welcome and at ease, to feel like any other pregnant woman at an OB-GYN office.

"Because until we normalize this as much as possible, people won't seek treatment or they'll fear the criminal part of it," says Spears. "That's the whole reason we created this center and put it in the area we did."

That fact that WISH Center is in a medical office building, not a hospital, is intentional. "We put it in the same area as other physician offices because you need to feel like that," Spears says. "It needs to feel like you're doing any other routine OB visit that you encounter. It can't feel like a heroin treatment facility. People aren't going to go to that."

But there are important differences from other OB-GYN offices.

For instance, WISH Center offers women who are in withdrawal handheld showers in rooms with special drains. "The reason why is if that mom gets sick and vomits on herself when she's going through induction of buprenorphine, we wanted her to be able to take a shower," Spears says. "Because that's a dignity issue. We keep clothes there. So she could change and not have to leave in vomity clothes."

Pregnant women addicted to opioids often feel an intense sense of shame and stigma, which is a big reason many don't come in for treatment, Spears says.

"They're committing the worst offense against humanity in many people's minds," Spears says. "That's what people are so judgey about. Let's not judge them. Just open the door, be so glad that they sought out help and take it from there."

Chad Sabora, the co-founder of the Missouri Network for Opiate Reform and Recovery in south St. Louis, says that Shyken and the WISH Center are doing "amazing, crucial work."

The WISH Center "is a piece of the puzzle that needs to be in every state. And we need to keep families together," Sabora says.

Sabora contrasts the thinking behind the WISH Center with punitive attitudes in places like Tennessee, which in 2014 passed a law that empowered local law enforcement to lock up pregnant women who abuse drugs.

"You got a pregnant woman? Lock her up," Sabora says. "There's no prenatal care in jail. It's the most absurd, ass-backwards solution to helping a pregnant woman with an opioid disorder. Tennessee is a shining example of the mentality of a lot of this country. 'Get that woman in jail.'"

The WISH Center's emphasis on preserving the mother's dignity is why she keeps coming back after initial misgivings, Clemens says.

"They are this good and this professional," she says. "Because most people, when they think drug-addict mother on Medicaid, they're going to go to some clinic. They're going to sit there for five hours, nobody really gives a damn. It's so nice to be able to come to a place like this."

Shyken has been a huge part of what keeps her coming back.

"When I very first met her I was definitely overwhelmed and scared," she says. "But she talks to you, she explains everything to you, she walks you through everything. I mean, she just makes you feel comfortable. Like, 'You can do this and get through this.'"

Shyken did not begin her career thinking she would be working with pregnant women addicted to opioids.

After graduating from Ladue Horton Watkins High School in 1972, she majored in music at Indiana University. She then attended the University of Missouri for medical school and Washington University in St. Louis for a fellowship in high-risk obstetrics. Today she's an associate professor at the Saint Louis University School of Medicine, department of obstetrics, gynecology and women's health.

A lover of vigorous exercise, Shyken, now 63, is a dedicated cyclist and yoga practitioner and instructor. This month, she's launching a yoga class for recovering addicts modeled on 12-step recovery groups.

Shyken began working with chemically dependent women in the late 1980s, a time when the crack-cocaine epidemic was in full swing. The current opiate epidemic is something different. It has hit harder, across all aspects of society.

"It's not just middle-class kids with helicopter parents," Shyken says. "It's all of us. It's reached all aspects of our society. Nobody is safe. This is an equal-opportunity disease."

Shyken blames its reach in part on her fellow physicians.

Two decades ago, Purdue Pharma, the company responsible for OxyContin, deluged both physicians and consumers with marketing appeals that falsely described OxyContin as safe and non-addictive if prescribed properly. It was neither.

At the same time, many American physicians bought into the idea — which was heavily promoted by Purdue Pharma and other drugmakers — that pain was being under-treated. So doctors too often over-prescribed opiate painkillers to too many patients for long periods of time, inadvertently getting them hooked.

As a result, while America represents five percent of the world's population, it consumes 95 percent of the world's opiates.

"There are just a lot of opioids out there, through the over-prescribing of opiates," Shyken says. "I think that we operated under a misimpression that opioids, when used legitimately, did not result in a high risk of addiction. And we were wrong. Dead wrong."

About a decade ago, as states like Colorado and Washington began legalizing medical and recreational cannabis, Mexican drug cartels switched their resources from weed to heroin and fentanyl. The result: a glut of very powerful street drugs at historically low prices.

Throughout St. Louis, for instance, a "button" of heroin costs as little as $10, while the average waiting period to get treatment for a substance-abuse addiction can stretch several months or more. For opiate abusers and their families, a grim truth inevitably emerges: It is much easier to get high than to get help.

"You know some people come to their addiction because of peer pressure, particularly kids," Shyken says. "Some people come to an addiction because the first time they try an opioid it makes their problems go away. They feel awesome. And they probably have a genetic predisposition. That's another piece of the issue: It's hard to measure prevention. And it's hard to know what in terms of prevention really works."

Something else has happened to turn opioid use into a crisis. And that's a shift in the way American society deals with problems, Shyken theorizes.

"I think we've become a society that tolerates very little and expects instant relief in the way of a pill," she says. "So we've marketed ourselves into this situation. Whatever the situation is."

Married to a primary-care physician, Shyken is herself the mother of three grown children. Like any other mother, she worries that her offspring might get into drugs. She lectures them all the time, she says.

"And the message is, 'Not even once,'" she says. "You think I'm not curious? And knowing who I was when I was a teenager? By the grace of God."

Despite all the painful stories she's heard and seen up close, Shyken says she feels optimistic about her patients' ability to move forward with their lives.

"This is unbelievably rewarding work," she says. "Somebody comes in as an addict and they're pretty desperate and they've done some pretty awful things to support their habit, and then you put them on MAT [medication-assisted treatment] and then the real person comes through. And they're so grateful."

Interstate 55 snakes southward from St. Louis parallel to the Mississippi River. The highway rolls through the hills of Jefferson County, through towns named Imperial and Herculaneum, before bringing the traveler to Festus, with a population of slightly more than 11,000.

On a recent evening, the town is quiet, a postcard of small-town America. But Tim Lewis, the town's police chief, sees a different side — the human toll of the opioid crisis that hit his town going on six years ago.

"I've been a policeman for a long time, but I've never seen the heroin as big or as long-lasting as it's been the last few years," Lewis says. "It just took off. Overdoses of opiates. Prescription drugs. Fentanyl. They're all part of the problem."

The purity of the product has gone up while the price has gone down in Jefferson County, he says. "I've been a policeman a long time. When I first started, a button of heroin would cost you $20 or $30. And it might be ten or fifteen percent pure heroin. Now a button costs you $5, and it's 90 percent pure heroin. So the market's flooded."

This is the world Clemens returned to after her release from prison in September 2016. She'd done ten months for drug possession, but quickly started taking Percocet after her release — a mistake she blames on the decision to hang out "with the wrong people," she says.

About six weeks after she began using drugs again, she found out she was pregnant.

"And I caught myself. Because I refuse to let other people influence me anymore," Clemens says. "Because I used to be so, 'I want you to like me, I want you to hang out with me,' type of person. I don't care anymore. I don't care if I don't have one friend. Because at the end of the day I have my kids and I have my family."

She's been using drugs for a long time. Linda Clemens thought of her daughter as a star member of the high school softball team and remembers being horrified to find Rio passed out in her bedroom at nineteen, a syringe nearby on the floor.

"I was shocked because I never dreamt she'd do anything like that," Linda says.

Since then, she adds, "the whole family's been through hell. Because the first few years I tried to hide it from them. And then I just couldn't anymore. Because financially she drained me. Between buying drugs and paying for lawyers, I had to file bankruptcy a few years ago."

Even getting pregnant with Kylie didn't change things for Rio, not in a permanent way. Rio recalls that her physician at the time "didn't know much."

The doctor "knew the basics of addiction and pregnancy, but I was never monitored or prescribed medication through him," she says. "He did the minimum when it came to the addiction part of being pregnant."

In addition, Rio had to find a different doctor to get on Suboxone; her OB-GYN didn't handle it.

Her pregnancy allowed her to move ahead of the long waiting list of patients seeking prescriptions for the drug used to wean addicts off opioids. But after Kylie's birth, she ended up using again. Linda had to take custody of the little girl while she was in prison.

Rio knows she will one day have to explain her drug problems to her daughters.

"I mean, this is the one thing I get emotional about," she says, tearing up. "They say, 'Get clean for yourself.' But I did this for myself so I could take care of them because I'll be damned if they end up like me. I will be damned if these kids go through what I had to go through."

Opiates are big problem in Jefferson County, Linda says.

"I know a lot of people she went to school with who are dead, they're gone, they ODed," she says. "I actually think it's because there's not a lot for them to do down here. There's no place for them to hang out or go. In the beginning drugs are cheap. Because all there is to do down here is people get together, they drink, they have parties."

Linda says she didn't even mind the ten months that she took care of her granddaughter full time.

"I was just happy she was still alive," she says of Rio. "Because so many people that I know that she was friends with aren't."

After the ultrasound test ends, the Clemens clan follows Shyken to another examining room to talk over Rio's progress in staying sober and getting ready for the birth of her second daughter.

Shyken praises Rio for her compliance. "And there are some people who are not as easy to take care of as you are," Shyken says.

"She wouldn't have been a couple years ago," Linda says.

"I know," Shyken says, turning to Linda. "I know I'm reading your mind here, because I can do that, you know. I mean, you're probably less optimistic than Rio is."

"I never want to get my hopes up, you know," Linda says. "I have so many times."

"This is part of the dynamic. But there are family members who really sabotage you," Shyken says. "Either because they've been using or they've been hurt too many times."

"I try always to be there for her," Linda says. "I got her to come back here, because I read about it online and I didn't know where else to go. I said, 'You need to go back there. I will take you. You're going back.'"

"I was just overwhelmed," Rio says. "I honestly didn't think I could do it, and it's just scary, you know. You just have to think to yourself, 'If I could do half the things in my life, I could do this.'"

"I'm so proud of her, I can't even put it into words," Linda says. "I'm thrilled. This place is a godsend."

Rio turns to her mother. She collects her thoughts, thinking hard about what she wants to say. The words tumble out slowly, with difficulty, and her voice shakes.

"Mom's always been there for me. She's never left. She's never kicked me out. She's never told me I am not allowed in the family," Rio says. "She's never sat there and talked down on me. She just kind of accepted it."

Linda shifts her weight and looks on as her daughter sums up the past decade.

"Even though she was helpless and she couldn't do much until I wanted it, you know," Rio says. "She just kind of cradled me and tried to make sure nothing happened to me to the best she could."