Saint Louis University is having a bit of a statue problem.

The statue, a proposed monument to the Occupy SLU movement of students and protesters who camped out on the school's midtown campus for six days in October, has raised the self-righteous hackles of some of the Jesuit university's alumni. Some donors have threatened to cut off support. One alumna told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch she closed her wallet because SLU president Fred Pestello chose to negotiate with the protesters, a sign that the St. Louis institution is becoming a "liberal environment."

Indeed, with all the hubbub over Pestello's handling of Occupy SLU and subsequent donor condemnation, you'd be forgiven for thinking the recent news coming out of SLU is, well, new. You would be wrong. A look back at the 1969 occupation of SLU's Ritter Hall reveals that negotiating with protesters has long been part of the university's heritage.

See also: Here's the Agreement that Ended the Occupation of Saint Louis University

It was April 28, 1969, when a group of black SLU students from the Association of Black Collegians took over an office within Ritter Hall, which sits on North Grand Boulevard just east of the main midtown campus.

The occupation was a product of what University News described at the time as "outright inequalities of the white structure and its more subtle discourtesies." The student newspaper devoted its May 2 edition to analyzing the occupation, and the language is strikingly familiar to the stated goals of the Occupy SLU protesters more than four decades later.

Here's how the front-page University News article from May 2, 1969, titled "They Said it Couldn't Happen" led off:

Monday, April 28, came and what "could not happen at St. Louis University" did. Black students, disappointed over the University's failure to make extensive commitment to it's own internal black community, took action to dramatize their position. Plagued by both outright inequalities of the white structure and its more subtle discourtesies, and irritated by a recent increases incidents of harassment, the blacks apparently found themselves moved to a position where they either did not view resolution of their problems possible by following the lines of existing channels, or else had reached a point of unwillingness to tolerate injustices and discrimination while problems were solved at the leisure of the formal system. Confronted with a system which they viewed to unresponsive to their requests and problems, they stepped cautiously, but clearly, outside of it.

The story (embedded in full after the jump) goes on to describe how the group of black students arrived at the office and asked the secretaries there to "please, take a coffee break." When the secretaries balked, the black students made the same request to an assistant dean, who then agreed to let them take over the office.

Twelve hours later, the occupation ended. Critical to the resolution were the six hours of negotiation held between black students and university officials, including then-SLU president Reverend Paul Reinert. By the end of the negotiations, the students and school officials agreed on a list of demands. School officials signed a letter promising that "Every effort will be made to correct the undesirable situation listed by the Black Collegians."

The demands themselves included an official investigation into harassment of black students, hiring more black supervisors in the maintenance department, hiring more black security officers, integrating black culture into the academic curriculum and creating an office of Black Student Affairs.

In a press statement released the next day, Reinert defended his leadership to those who wondered why he didn't invoke SLU's established policy of removing protesters from school property, with force if necessary.

"To call in our security police to remove the students would not only have severed relations with our black students, but also would have ended a meeting that, in the long run, can only prove highly beneficial for the University," Reinert said.

"Consequently," he continued, "I believe that everyone gained from yesterday's meeting. No damage done; no one was injured; there was no significant disruption of campus activity. Rather, the meeting and the statement that evolved from it represent a re-dedication to our values and our goals."

See also: Protesters Occupy Saint Louis University, Promise Further Civil Disobedience After Shaw Shooting

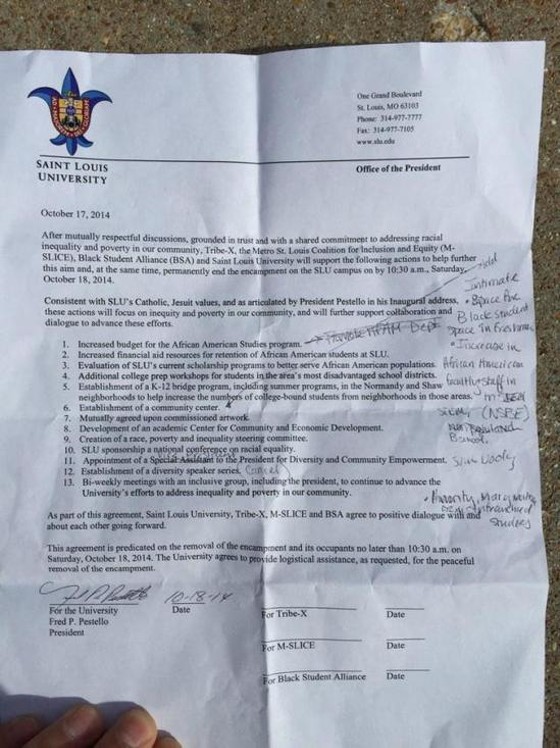

The 1969 demands share more than a few similarities with the Clock Tower Accords, the name given to the thirteen-point agreement between SLU officials and three protest groups which ended Occupy SLU

Signed by Pestello on October 18, the document included demands for greater funding for African American studies, the creation of a SLU-sponsored conference on racial equality and, of course, a "mutually agreed upon commissioned artwork" that would capture "the spirit and importance of the demonstration and encampment at Saint Louis University on October 13-18, 2014." Currently, the university campus boasts more than 60 outdoor sculptures, and the one that depicts African Americans -- a shackled slave woman -- is kept in a space only used for private events.

According to an official January update on the Clock Tower Accords, the new statue is expected to be completed in about twelve months.

So, while the controversy over the statue continues to roil the SLU community, it's probably worthwhile to look at the history of a university whose students are, to this day, clearly proud of its civil-rights legacy.

And although Pestello is still feeling the heat from donors and alumni, he could take some comfort from the eventual career arc of former SLU president Reinert, who went on to serve as president until 1974, then chancellor until 1990. Reinert's legacy was immortalized on the St. Louis Walk of Fame shortly after his death, at age 90, in 2001.

Continue to read the full University News coverage of the 1969 occupation of Ritter Hall.