In the chaotic days following the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Wendell Phillips "Phil" Berwick found himself drawn to St. Louis. A married father of four and owner of a tree service company in Jefferson County, Berwick spent 21 days praying, singing and otherwise spiritually engaging, crashing in a temporary tent in a shuttered KFC's back parking lot.

Months later, the lack of indictment for officer Darren Wilson set off another round of protests. A small act brightened those devastated communities — Paint for Peace, an informal group of artists who covered shattered storefronts on Ferguson's West Florissant Avenue with hand-painted plywood art. Berwick avidly signed on to the effort.

A sketcher and doodler since childhood, Berwick felt Paint for Peace light a fuse inside him. "Hundreds of artists came together to paint boards..." is a riff he comes back to, frequently.

Last August, one year after Brown's shooting, Berwick and his wife Theresa, whom he calls Tree, moved to Ferguson, into a handsome ranch house just across the street from Jeske Sculpture Park. And in the eight months since, Berwick has become a street artist. With his friend and employee Kevin "Kapp" Gary, he's responsible for erecting plywood boards across St. Louis featuring the bearded half-man, half-tree character he calls Merferd. The trees that accompany Merferd are his "treetoons."

The boards aren't legal. Berwick doesn't get the permission of property owners before he nails them onto the walls of buildings or erects them by the side of the highway. Nor does he follow the accepted code of street art, in which artists respect each others' handiwork –- Berwick proudly paints over graffiti depicting vulgarity or violence, using Merferd to transform work he considers ugly. With a street preacher's zeal, he's convinced he's making greater St. Louis a better, more beautiful place.

He has his fans — including, on one recent overcast morning, a city employee who admires his handiwork while stopped at a red light near the busy intersection of Gravois and Arsenal.

The man is a passenger in a city water truck. He gives the boards a long, hard look and then calls out to the pair standing on the corner.

"Who does those?"

Gary points to Berwick, a wiry, tanned 60-year-old with a thick shock of black hair. Berwick nods that, yes, the trio of boards affixed to the building are his creation.

These Merferds are more visible than the one Gary and Berwick added to the same building earlier in April — largely because Gary has just chainsawed down what Berwick calls "an unruly bush," a Rose of Sharon that cropped up along the curb line and grew to a height taller than either man.

While other pieces Berwick installs are overtly faith-based, with small slogans or single words of encouragement, this group is simpler; the outer Merferds wave towards the one in the middle, whose bushy face looks out into the street. They're positive, but subtly so.

"I see these up all over the place," the water worker says. "I like 'em, man, I like 'em."

As the truck drives off, a young man in the next car shouts out a bit of similarly worded encouragement: "Keep it up, man, keep it up!"

The home of Operation Brightside is a low-level streetfront building just a few blocks from the Missouri Botanical Garden. Brightside's little corner of the city is pleasant, quaint even, despite the hundreds of cars that pass nearby every hour along the bustling intersection of Vandeventer and Kingshighway.

Operation Brightside's mission, in a sense, is to give the city of St. Louis a bit of this vibe, on a much larger scale: Brightside's corner of the world is family-friendly, pleasant, charming. And, of course, the other part of the mission — and it's a big one — is the eradication of street art that suggests very different qualities.

Heading up the non-profit is Mary Lou Green, who brings a sober, steady, no-nonsense tone to her graffiti eradication efforts. She can describe the operations portion of the job with uncanny precision.

"In 2015, we removed graffiti from just under 4,000 vandalized properties," she says. "Since the beginning of this year, we've removed graffiti from 700 homes, businesses and public structures. One of the things that's really driving your cost up at this point is that often there might [have been] a little tag here or there; now vandals are spreading graffiti across an entire wall. It can be hundreds of feet long. And that requires a lot more resources, time and materials to remove graffiti."

About $300,000 in annual funding comes from a federal block grant; last year, the nonprofit raised an additional $26,000 from private sources. Green figures that Brightside will need about $4,000 more than that this year to support its five-man anti-graffiti crew.

Calls for paint removal can come from individuals directly reaching out to Brightside or referrals from the city's Citizens' Service Bureau. Organizing all of those moving parts is what Green does, every workday year-round.

She doesn't spend much time wondering about the motivation involved, how the graffiti crews are socially constructed. In a sense, she's not even that curious about the motivations of the most prolific graf writer of recent years, Super.

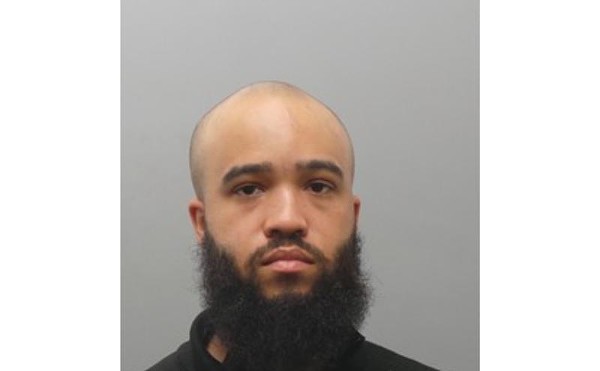

On April 5, St. Louis Police arrested David Cox, 33, and identified him as Super. The pending legal case against Cox, represented by high-profile attorney Scott Rosenblum, involves a specific handful of Super tags, ones traced to Cox's presence on-site through video or visual surveillance, according to court records.

The handiwork of Super, though, goes far beyond those handful of pieces; his tag is found everywhere in St. Louis from phone poles to highway underpasses, from alley garages to high-up warehouse windows. When Cox was arrested in a Cox Roofing Company shirt, the popular response among those who pay attention to graffiti in St. Louis was a collective "aha." That job, after all, would afford someone tools of the trade (ladders, ropes), coupled with a comfort level with high-up spaces.

Berwick's tree care service, Living Tree, offers him a degree of advantages to do street art, too: a bucket truck, ladders, climbing gear.

Green, while declining to discuss the reasons or motivations for Berwick's public art binge, does say that she's exchanged emails with him, and that she's tried to offer him some curbing guidance. (Ironically, his company once, years ago, won a tree-trimming account with Brightside.)

Even with the best of intentions, she says, guerrilla street art actions are what they are: illegal.

For her, it comes down to permission. "If a building owner has asked for a mural, Brightside will respect that," Green says. Without permission, "any graffiti vandal can be arrested for breaking the city building code."

And yet Berwick, who doesn't have that permission and is operating in broad daylight, remains free from enforcement. John Harrington, who organizes Paint Louis, which brings together street artists on the Mississippi's flood walls for an annual sanctioned event, has a theory as to the reason for that.

"My personal opinion is that Berwick is able to do what he does because he paints peaceful tree characters and he's a Christian," Harrington writes in an email. "If he was doing swastikas and pentagrams, they would hunt him down. I think as long as he stays positive they will let him keep going."

For years, there was something of an unwritten code on where graffiti, and other forms of underground street art, like wheat-paste posters, stickers and stencils, might appear. Occupied buildings were generally off-limits. Ditto certain types of buildings, including churches and schools. Hitting brick was frowned on, as removal efforts can damage tuckpointing.

These days, those notions seem hopelessly outdated. Neighborhoods in which graffiti writers live and play — like Cherokee Street and South Grand — have taken some particularly hard hits, and the city's classic red bricks have not been spared. Industrial areas, such as the factory-and-warehouse districts south of downtown, are magnets, as are zones along major thoroughfares; a drive down I-70 from downtown to Berwick's Ferguson, for example, offers an ever-changing, illegal gallery of today's active graf writers.

Among the businesses that call for graffiti removal, says Brightside's Green, many are repeat customers. She notes her nonprofit's popular mandate, with money "raised through private funds, tax-deductible donations. Individuals support us, large and small, as well as foundations," she says. "Really, it comes down to the fact that the vandals are showing a great deal of disrespect for our community. The people who want to support Brightside want to make it a better place."

In essence, how badly a city or region is touched by graffiti owes to the relative ethics of those doing the painting. Berwick, not surprisingly, has his personal code, even though it differs from many other artists.

"Once a building's roof has gone," he says, "the building's gone." To him, that means it's "open season" for painters to move in and add blasts of color and messaging.

And the city of St. Louis is still a place of plentiful broken building stock. While many, if not most, would look at cracked, crumbling brick buildings as hopeless, Berwick sees at least a chance at redemption.

"There's power in words," he says, closing his eyes. "There's power in art."

He pauses, as he'll sometimes do when reaching for an idea. He can envision a city in which graf writers are given amnesty, solely on the condition that they work out in the open, on plywood attached to burn-outs and any other building with a half-decade of abandonment.

Discussing it, he recollects his time with the Paint for Peace effort. He wants to see if the legion of current graf writers have more in their creative quiver than an ability to quickly write their handles.

Just last week, he petitioned St. Louis Comptroller Darlene Green for this type of permission.

"We have an opportunity in St Louis to create an atmosphere of hope, peace, respect, and unity through live demonstrations of the arts," he wrote. "To have an impact, this will have to be done outside artist's studios, and in various selected places in the city where thousands walk past and drive past every day."

Berwick is no hypocrite, refusing to play where he sleeps. Three Merferds also dangle from the trees in front of his home. (Not surprisingly, he's already added his own, non-commissioned piece to the collection at the sculpture park across the street, including a book that dog-walkers can sign, housed in a lockbox, atop a tree trunk.) Two massive paintings of murdered St. Louisans sit propped up against his garage door, striking portraits of the deceased painted upon his preferred medium of plywood.

By enabling these types of projects and bringing street art out into the open, Berwick believes that graf writers, who often stick and move with fast, sloppy messages, will rise to the occasion and up their work. He really believes this.

"The taggers are armed and ready to paint," Berwick says. "That is, armed with paint. This is why I'd love to see the city, rather than looking at them as antagonists and enemies, let them come into the Paint for Peace community. We want to get the city on board. Everyone who's proud of their name and shows some real talent should paint some themes, love and forgiveness. Do it during the day, so we can watch you. I want to stress that if it's a functional, livable building, then you have no business on it. But if it's a goner, let's have painters add sensitive stuff: flowers, nature, names.

"You have these taggers coming out at night," he surmises. "They're doing what they're doing at night, so they don't get caught. I look at some of the art. It's on buildings that are irreparable. The heights, man; I have admired some of the heights they're working. I'm intrigued. They don't have a bucket truck! How are they doing that? I'd love for us all to be able to view that during the day. It'd be exciting, as exciting as watching someone climb a mountain."

On this point, Harrington, the Paint Louis organizer, agrees.

"Whether [Cox] is Super or not, the city needs a scapegoat," Harrington says in an email. "Instead of reaching out to artists and doing city beautification projects by letting the artists paint community-based murals on all the abandoned buildings in the city, they vilify and write them off as criminals. Most of the artists just want notoriety, but most galleries don't look at what they do as art, and regular people can't read it or tell the difference between street/urban art or gang writing." Thanks to those conditions, the artists have no choice, he says, but to paint outside the lines.

But there are, of course, places where time is taken for large-scale works. Places where graffiti exists in an almost-curated state. Places that few see.

Some months back, a group of friends including Washington University adjunct and architectural historian Michael Allen paid a visit to the old Central High School at Garrison and Natural Bridge, closed for about a dozen years now. Unlike some buildings that offer unusual viewpoints of urban exploration, this visit was somehow sadder, knowing that these empty hallways and classrooms were, for just over a century, a vital part of the city's educational system. Today, few remnants of what was remain, despite the complex's large north-city footprint.

"I think it's got an overwhelming sense of the uncanny mundane," says Allen. "The place has been stripped of all the vestiges of students. Other schools are full of display boards, borders made with construction paper. At Central, there's nothing to indicate the life of that building. It's all about beige-painted plaster walls. Lockers, collapsed ceilings, buckled floors. It's all the same. It really just makes you aware that abandonment can be kind of boring. It boils down to something that's not visually striking.

"What gives the school such a rush," he continues, "are the views from the windows and the roof, looking out across north St. Louis, over this tree canopy leading to the Arch. And then there's the graffiti on the building. What the building lacks in other color has been brought back by these really large-scale pieces, impressive in their use of color and imagination. I saw pieces that depicted Agent Cooper. Some animal pieces, like an intricate deer. There were some things that you don't see on exterior walls. Here, they felt like delicate pieces of fine art, delicate works of art. It's like they wanted to put them into spaces that won't get immediately bombed. They're safer there, like paintings put in a storage vault. I appreciated that. It was almost like going in a museum. These beige walls, all the pieces lined up."

Wryly, he adds, "and like a lot of museums, the entrance is hard to find."

Allen may see things differently than many of us. Graffiti, for example, is something we all see in the city, but we run the results through very different prisms. Some people call the work of artists like Super "blight." Allen sees a city with significantly more paint than just a few years ago — and some of it he likes.

"When I started exploring, the world of graffiti was dominated by a handful of old-guard figures, by this point. Veks, Redd Foxx; you'd see their names in a lot of different places. Now, there's too much to even know." He references Merferd and the artist crew who reiterated the message "Free the Herb," then adds, "There are a lot more brazen acts of graffiti on occupied buildings, along Cherokee especially. Graffiti used to follow vacancy. You don't see it in the West End; in the Loop, there might be a Sharpie mark on a lamp-post. But on Cherokee, almost every building's been tagged with entire-wall-sized pieces."

With the arrest of Super, he says, the conversation's taken on a new, mainstream conversation. Before that, he says, "I can't remember the last time I picked up a newspaper and saw the arrest of a tagger. It wasn't in the press and wasn't something that the police bragged about. That says something over how big a part of the city it's become."

He adds, "It almost used to be a game to find a good Ed Boxx piece. Now you can get out and circulate and there's a lot more stuff; just not as high-quality."

What's driving the increase? Allen speculates, "There seems to be more permissiveness. Or the fact that more young people flock to the city and feel more confident in wanting to express themselves.

He adds, "I think a lot of taggers are white males that grew up in the suburbs, and ten years ago were not as likely to have lived in the city. Now, I think there are a lot more of these taggers living in the city, tagging in the city. They're here, rather than coming in from the county and doing a signature piece."

Driving out to Ferguson to meet with Berwick at his home, an amazing sight bursts off a weathered billboard near the Shreve exit of I-70: It's unquestionably Merferd, in a simple black-on-white-on-distressed wood. "Drive Nice," he implores passing motorists.

The piece was stirred by an incident in which one of Berwick's four daughters was the target of road rage near that exit. He took to the vacant billboard on a recent weekend, he says, to paint the message and stop something worse from happening.

Like some of Berwick's other stories, there's a sharp intensity in the way he tells it; at moments, his stories feel as if he believes that the city of St. Louis, the whole region, really, has been pushed to the brink by violence and decay. A portion of his work shouts of this sadness, like the major pieces sitting in his driveway: He imagines creating a painted piece of plywood for everyone murdered in the city, what he envisions could become an all-encompassing project.

Even though the first two pieces haven't been cleared for a public display, he can imagine them going up everywhere that violence strikes, graphic reminders of those who've passed.

When he describes ideas like this, you can imagine the younger Berwick, who moved to the area from Chicagoland in 1988 to enter a seminary, the evangelical Christian Outreach School of Ministries. It was "torched by some Satanists," he says, and he returned to the tree business, which his wife, in a dream, dubbed Living Tree. (The seminary, which is based in Hillsboro, later reopened.)

Berwick's eyes close, his voice trembles, he takes on the spirit of a charismatic preacher at moments like this. There's a mission in his voice.

"Over the years," he says over dinner, "my passion was in saving trees. But both of us really feel that the hour has come to save our city..."

"From itself," adds Gary.

"Without sounding ridiculous," Berwick adds, "we feel a call to do our part to save the city."

"Somebody's gotta do it," Gary interjects. "And I would like to be a small voice, even a large voice, in the city succeeding, in saving itself. The people, the neighborhoods, the buildings... we should love everything in our community. It's not being expressed."

At Montrey's Cigar Lounge, a comfortably desegregated, "salt and pepper" bar in the heart of Ferguson, Berwick and Gary discuss how they met. A work services company sent Gary to Berwick's company last year. With a decade of experience in the tree business and carpentry skills too, Gary, now 41, intended just to go to work for Berwick. Instead the two men became fast friends and true collaborators.

Though together every day for work (Gary is Berwick's sole employee), they socialize, too — including a Saturday night Bible study that they both attend weekly.

"We encourage each other as men," Gary says. "All men need encouragement from one another, for one another. A woman can't encourage you to do what you love the way another man can. It takes another guy, or group of guys, to say, 'That's a good thing you're doing. You should do that more.' It's about building each other up."

Their families joke about the amount of time they spend together; each adds onto the other's thoughts and ideas. While Berwick is the idea guy, Gary adds a sharp wisdom to things, filling in the gaps in Berwick's original plans.

And Berwick's plans ... well, they come in bursts of enthusiasm that are hard to exactly describe.

One example: At River Gypsy, a wood-recycling facility on the edge of northern downtown, Berwick's suddenly hit with the idea to capture video of a new, river-riding Merferd being cut out of plyboard. Pitching himself onto the street pavement, with the fluid movement of someone decades younger, Berwick not only gets the footage he needs, but does it while narrating the story about how his work's popped in recent weeks.

"I put one of the Merferd videos on Facebook," he says of a large graffiti touch-up at Grand and Gravois. "I bought $11 worth of Facebook promotion and we've gone viral." His "Merford and the Treetoons" page on Facebook has jumped in popularity, with more than 1,000 likes, most gathered over the past few weeks. Increasingly, Berwick captures the work he and Gary do on video, throwing himself to the pavement to line up a perfect shot on his iPhone.

And herein lies one of the mysteries of their mission and its future.

Berwick and Gary are doing their work in broad daylight, unabashedly showcasing the work on Facebook. They're altering pre-existing works, originally done by folks who don't always take kindly to cover-ups; now some of their own are getting bombed in return. They've been told, directly or through back channels, that putting up boards on abandoned, but owned, properties drifts them outside of the center lane of law.

And, yet ... when they're talking about what's next, it's a "when" not "if" discussion. And they're having this conversation on the record, with a reporter.

They believe too deeply in what they're doing to slow down. Why even bother to question the rules? They'd rather see things as they could be and question why not.

Of Gary, Berwick says, "It does have more impact because we're a black-and-white team. He's been a huge encouragement for me. There're times when he believes in Merferd more than me. He's multiplied the success of it. When we're talking about what's next, we have this thing we say: 'Really?' 'Seriously?'

"We need to keep doing it. I can't stop. We will change the city."