Mary

Titled "Silent Killer," this three-panel painting depicts Coldwater Creek and the individuals who may have been irradiated by exposure to it.

When Mary’s painting, “Silent Killer,” hung in the Millennium Student Center at the University of Missouri- St. Louis, she talked to a number of students. Many asked her about the painting’s subject: Coldwater Creek, the nuclear threat that runs right through Mary’s backyard and may be the cause of her cancer.

Some people wondered aloud if the contaminated area is where north St. Louis County’s urban legend of “Bubblehead people” came from. But only one already knew about the creek. Mary, who asked that her full name not be used because she is private about her illness, wants her painting to change that lack of awareness.

“The people that lived here before us both died of cancer. The person to my right, they’re fine except the father did die of cancer. There’s somebody who lives catty corner to me who has cancer.” She lists two more friends who have cancer, in addition to a few of her pets — two cats who died of cancer, a dog with a foot tumor. And then, she says, doctors discovered that both she and her partner had cancer, the diagnoses made within a month of each other.

“We went to radiation together. That was romantic,” Mary says, wryly. She suffered from breast cancer; her partner was diagnosed with prostate cancer.

Mary painted 25 small paintings of moths to get through chemotherapy. And then she created “Silent Killer.” She gathered found materials from the creek, then painted over them. Her style is “cartoonish,” which Mary thinks draws people in. “They think it’s going to be funny,” Mary says. It’s not. Instead, people discover paintings that depict the horror and frustration of living somewhere that might be killing you.

Starting in 1942 and continuing for over a decade, Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals — then known as Mallinckrodt Chemical Works — dumped waste from the Manhattan Project all over north St. Louis County. At the time, few lived there.

But as development radiated out from the central city, and residents moved to the suburbs, that changed. In some cases, the waste moved too. Some of it, which had been stored north of Lambert-St. Louis International Airport, was relocated to 9200 Latty Avenue’s Hazelwood Interim Storage Site, near Coldwater Creek, in 1956. The waste was left on the ground, open to the air; years and elements spread contamination, with the creek ultimately the receptacle for some say may be a particularly high concentration.

In 2008, former residents became concerned. A few years later, a group started gathering information. “We noticed all our friends were sick and dying, but we didn’t know what the cause was,” explains Kim Thone Visintine, who now helps organize more than 13,000 people in the Facebook group “Coldwater Creek - Just the Facts Please.”

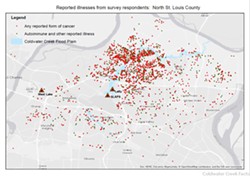

In 2013 the Missouri Department of Health & Senior Services released a report saying that cancer rates around Coldwater Creek were mostly normal. But that report was based on limited data; since then, an updated report found cancer rates that gave more cause for concern. And Visintine’s group’s public surveys — which found extremely high levels of rare cancers in former and current residents — in part provoked a reconsideration of the creek’s contamination. “The only thing we have in common is that we grew up in this community,” Visintine says.

Visintine calls the entire thing a “huge comedy of errors” — not because it’s particularly funny, but because the series of events, accidents and bad decisions that led to the current situation seem absurd. “It’s like nobody was talking,” she says. By most accounts, Mallinckrodt had no idea that residential areas would be affected (although the company has received criticism for its handling of nuclear waste).

The neighborhood was, as Visintine remembers, a “quintessential” middle-class communit — “everything you’d expect in Midwestern America.”

In her time as an accidental community activist, Visintine has seen a lot of frustration. “No one’s going to rush in and save the day. There’s no bad guy,” she explains. That makes it hard for some people to cope. “We can’t undo it.” The poison was unwittingly released decades ago, and now people are facing the consequences. Visintine herself lost her son to a brain tumor.

Visintine understands the urge to anger and protest, but doesn’t see the purpose in that. “What are you picketing?” she asks. Instead, from her perspective, the only thing left to do is educate.

Visintine recalls a friend of hers from high school. She was a bit of a drama queen. She also had a lot of migraines. Everyone at school thought her migraines stemmed from her need for attention. But a decade later, doctors found a brain tumor. She died. “We all discounted it,” Visintine says. Why would anyone have a brain tumor?

Visintine’s efforts now go towards making sure people like that now get diagnosed in time. She also works toward getting governmental restitution. There are various avenues, including the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, but Visintine says the financial restitution it offers barely covers the average deductible.

Katelyn Mae Petrin

The FUSRAP program surveys sites for radiation, then cleans up any causes for concern.

Visintine opposes a neighborhood buyout; she says she doesn’t believe it could even begin to cover the losses, financial and personal. Others are less sure. If the money were right, it wouldn’t be unwelcome. But some people — like Mary — bought their homes before knowledge of radioactive materials nearby cratered property values. The value of their homes are worth today, which is what they’d likely be compensated, will almost certainly not make them whole.

“We’re not a happy story. I wish we were,” Visintine says. “We’re just hoping raising awareness will keep someone from ending up with a terminal disease.”

The federal Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry is currently in the early stages of collecting data “to evaluate potential exposures to hazardous substances and how those exposures may have impacted public health in the past, present, and future,” a spokeswoman says. The radiation is definitely in the soil, but its exact health consequences are uncertain. Officially, the cause of elevated cancer rates in the area remains unknown.

What is known, however, is that as of 2015, 2,725 cancers were reported to Visintine’s group; more have been reported since. Additionally, the area sits on a floodplain, so contaminants don’t necessarily stay put. As the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has continued cleaning waste from the area, they have found more and more radioactive soil near homes. The cleanup is estimated to take another five to ten years, depending on funding and how many new sites are found.

“The thing about it is you’re not sure,” Mary says. A nine-year resident of Florissant and lifetime resident of north county, she fears environmental contamination could have come from several places. Maybe she was exposed while playing in a tributary in Ferguson, which she thinks might have contained radioactive runoff from the airport. Or her breast cancer could even be unrelated. It’s hard to tell.

The legacy of St. Louis’s involvement with the Manhattan Project is complex: Mary remembers hearing about at least one other nuclear waste cleanup project near her, years ago. And her husband at the time worked at Mallinckrodt. She wonders whether his Alzheimer’s could have anything to do with that job. She wishes she could test her own backyard soil, just to make sure it’s safe, but doesn’t know where to begin.

Next: A newcomer finds a way to turn tragedy to art.