Liz Stajduhar recalls the exact moment she "knew-knew" her boss was running a multimillion-dollar scam.

It was May 17, 2010, inside her downtown Clayton office. Her employer, Martin T. Sigillito — a lecturer in law, American Anglican bishop and member of the elite Racquet Club of St. Louis — was absent that morning. He'd scrambled off to Israel a few days earlier, promising to return with fresh funds to resuscitate his investment program.

As his trusted secretary of nine years, Stajduhar hadn't yet abandoned all faith. That is, until attorney Mike Becker of the downtown law firm HeplerBroom dropped by around 11 a.m. He'd been representing Sigillito in an overseas matter. Like Stajduhar, he had become intimately familiar with his client's business.

Sigillito's project was channeling private loans from St. Louisans and other Americans to a real estate developer in England. Conditions were ripe for growth there, Sigillito had promised. His man in the UK was an expert who knew how to spot lucrative properties and get things done.

But on that spring day, Becker brought the secretary some news that made him sick to his stomach: The entire venture was bankrupt. Sigillito had collected tens of millions of dollars, but there were barely any assets in England to speak of. Worse still, Becker said, the loan agreements did not permit Sigillito to divert new investments to pay off older investors — the very definition of a Ponzi scheme. Yet Becker had seen evidence of Sigillito doing just that.

Stajduhar, a career secretary, didn't know what a Ponzi scheme was. But she too noticed Sigillito shifting money around this way as early as 2006. Her boss had constantly reassured her that it was normal. In fact, she and her husband had invested.

Now she knew it was all a charade.

"I cried," remembers Stajduhar, a 34-year-old mother of two who has retained the high-pitched voice of a teenager. "Up until then, I'd only had a strong suspicion."

Two days later, in an e-mail to a major investor, Sigillito virtually admitted to paying off established clients with money from new ones:

My refunding efforts have borne fruit here in the middle east. I have some very likely sources who are on the verge....I know the urgency of [your] need for cash (I am in the same position, as you know). I am doing my best to have some hard data on all of this as soon as possible.

That same day, the FBI fitted the secretary with a wire.

Soon, the clergyman who collected rare valuables, who was driven around in a fancy car and who boasted of lecturing at the University of Oxford, was served three different search warrants and questioned by the FBI.

He was also hounded by investors worried about the money they'd entrusted to him. Many were blue-collar retirees, spread out from Arizona to Florida. But some were prominent members of the Racquet Club of St. Louis, a haven of the city's upper crust.

Paul Vogel, a former board member at the club and high-profile local businessman, not only invested his own family's money, but he also actively promoted Sigillito's scheme at one time, earning a commission in the process.

Sigillito's "program" has now collapsed into a tangle of civil lawsuits. One is a federal racketeering suit in which he stands accused by more than 50 plaintiffs of stealing some $45 million from them.

The feds have launched an investigation. In a rare twist, the judges of Missouri's Eastern District have already recused themselves from hearing any criminal matter involving Sigillito. The reason: His wife, Mindy Finan, is clerk to Judge Henry Autrey.

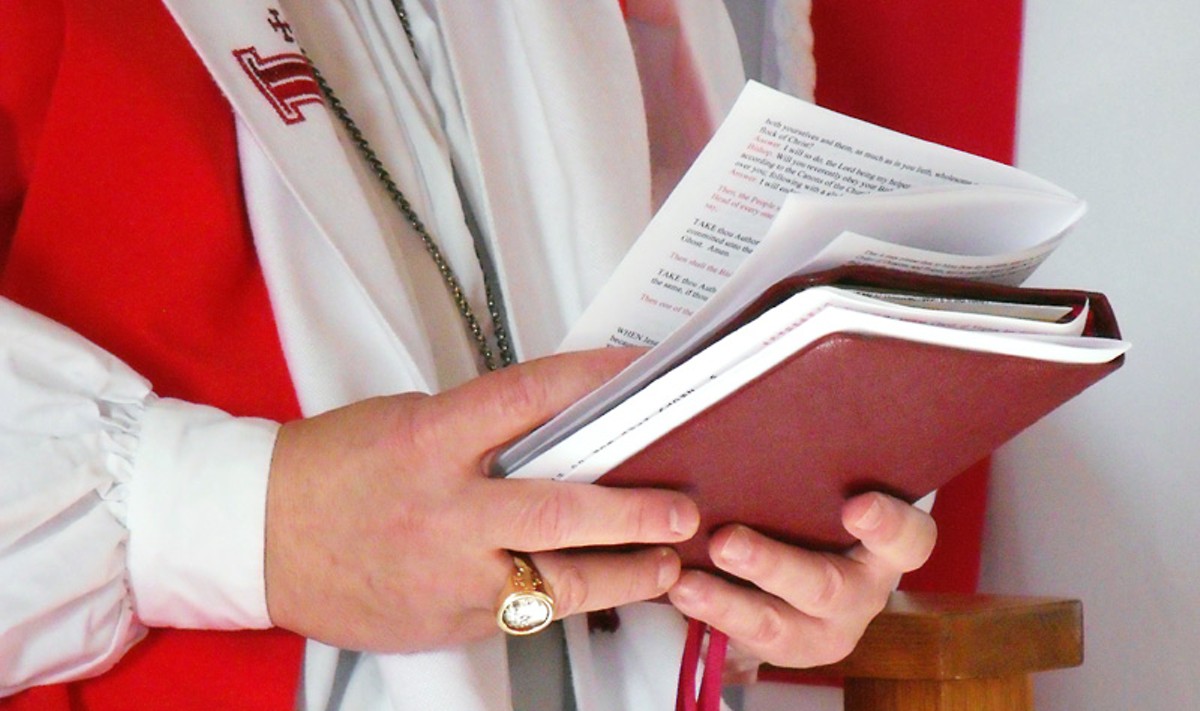

Meanwhile, Marty Sigillito still performs services for the small American Anglican Convocation on Sundays at Ambruster-Donnelly Mortuary in Richmond Heights.

"He puts himself out there as this sort of trustworthy bishop figure," says Sebastian Rucci, the Ohio lawyer behind one of the civil suits. "I wouldn't trust a thing that guy says, even if his tongue were notarized."

Until everything unraveled last spring, Marty Sigillito, 61, never behaved like a man strapped for cash.

He traveled to the UK six times a year or more. As Stajduhar recalls, he would regularly pay up to $6,000 for a roundtrip ticket in first class.

Stajduhar says that when she showed up to work at 7710 Carondelet Avenue around 8:30 each morning, Sigillito was already in the office. But he only stayed until 11 a.m.

At that time, Sigillito's driver — a man named Virgil — would pick him up in a black Lincoln Town Car and shuttle him off to lunch. He rarely returned, Stajduhar remembers.

According to documents from an Ohio-based insurance company, Sigillito owned a fifteenth-century book from Germany, insured for up to $120,000. His copper oil lamp, unearthed in the Holy Land some 2,000 years ago, was valued at nearly $30,000.

He also collected expensive antique maps, Persian rugs and British jewelry. Stajduhar says he was the kind of man who spent $5,000 on a bottle of wine, $1,500 on a pen and hundreds of dollars on lingerie (purchased for whom, she did not know).

Public records show that Sigillito was divorced twice in the 1970s and once in the 1980s. He has two sons and two daughters. He and his current wife, Mindy, now live on South Gore Avenue, a leafy suburban street in Webster Groves. Their 120-year-old home was recently assessed at $341,000.

He holds a bachelor's degree in classics from the University of Missouri-Columbia, a master's in European history from Cornell University and a law degree from Saint Louis University. He's a member of Phi Beta Kappa and a former Woodrow Wilson fellow.

He claims to lecture annually at St Edmund Hall, Oxford. But the university never employed him: He taught there as a visiting instructor for a summer program in Continuing Legal Education through the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

He was consecrated as a bishop in 2003. Stajduhar says he liked showing people his bishop's ring.

One Chesterfield couple, Barbara Otterson and her husband, Jim Gooderum, attended his services for a while. "He knew how to do everything he had to do during the service," Otterson says. "But I think he just wanted the title of bishop."

Three years ago, they arranged for Otterson's mother, who was suffering from Alzheimer's disease, to invest $300,000 with Sigillito's venture.

"We told him that was pretty much everything she had, and if anything happened to it, she'd be in trouble," Otterson recalls. "And he said, 'No, it's very safe, there's no way I can lose it.'"

She says they eventually left the church because she had a bad vibe about Sigillito. "Nothing sat right with me," she says. "The guy just rubbed me wrong."

The Racquet Club on North Kingshighway is a century-old den of dark wood paneling and mounted game animals. Here, St. Louis' lawyers, doctors and executives play squash, unwind in the steam room and chat over Scotch.

Members are tight-lipped about the club's inner workings. But Sigillito reportedly sat on the reciprocity committee, which oversaw agreements with other private clubs around the globe.

Paul Vogel, a board member, is the CFO of Millennium Brokerage Group and the CEO of Argos Partners, a consulting firm that handles estate-planning for the ultra-affluent. Sometime around 2005, he met Sigillito at the club. They shared the occasional cocktail.

Their spouses socialized, too. Vogel's wife, Lynn Ann — an attorney specializing in mediation and currently vice president of the Missouri Bar Association — got to know Sigillito's wife, Mindy Finan, at Racquet Club parties.

Soon, the Vogels were eating brunch with the Sigillitos after church on Sundays. They once visited what Sigillito referred to as his "country home" in Marthasville.

In May 2008 Vogel made his first family investment in Sigillito's English real estate program. Eight months later, Vogel flew to England to check things out firsthand.

Impressed, he described his experience in a due diligence report dated February 10, 2009.

Here's how things worked: Investors would scribble out checks to Sigillito, but these weren't loans to him, per se. The bishop was supposed to be middleman, raising funds for a fee. He would wire the cash across the Atlantic and into the hands of an Englishman named Derek J. Smith.

As Vogel explained it in his report, Smith was a former civil engineer in his sixties who'd carved out a valuable niche. England needed housing for its ballooning population. But development was banned in the greenspaces surrounding the towns to prevent ugly urban sprawl.

Smith's particular skill, Vogel wrote, was sniffing out plum parcels he knew could be rezoned for residential construction. Smith would purchase an "option," allowing him the right to buy the plot later at a set price. Once the rezoning came through, he'd snatch up the property and either bring in a savvy developer or just flip it to somebody else.

Vogel says he intended his due diligence report for family, friends and a few clients, at first. Of course, he wasn't the only Racquet Club member offering specifics on the venture.

A memo authored by R.C. Baer suggested that Smith was courting American dollars because many UK banks refused to finance real estate options, and the ones that did charged high interest. [Editor’s note: A correction ran concerning this paragraph; please see end of article.]

Your dollars will be safe with Derek Smith, the 41-year-old Baer assured his clients — and not simply because of his near-impeccable credit rating. Smith also owned twice as much as he owed. In other words, even in the worst-case scenario — Smith defaults on every loan, and all the Yankee lenders sue to recoup their losses — the Brit could, in theory, sell off all his properties and placate everybody.

For example, he could offload Hinton Grange, a charming boutique hotel for "discerning romantics" two hours west of London, near Bath. Or Little Farm Nursery, an "active income-producing" garden operation sitting on ten acres in Maidenhead. (Vogel, during his visit, toured both.)

These two assets alone — valued at a combined $23 million — raked in enough business revenue to pay the Americans their interest, should Smith make some bad option trades. Baer found this "very comforting."

The "key" to everything, he wrote, was Martin Sigillito, whose "expertise" and "constant monitoring" made this an "excellent opportunity" for "high-yield."

"Almost all of Marty's family money is invested with Derek," Baer wrote to interested parties, adding: "any money you would invest would be alongside my money, as well!"

And invest they did. Former Racquet Club president Mark Merlotti and his wife, Cindy, bought in. So did local developer and former board member Clark Amos, along with his son Preston. Tom Bertani, the club's general manager, put in funds with his wife, Donna. None returned calls from RFT. Baer likewise declined to comment for this story.

One secretary at the club, who declined to be named, lost both her brother and his wife to cancer in two years' time. Combining their life-insurance payouts with other family funds, she entrusted $900,000 to Sigillito. The hope was that it would grow and help her raise her two young orphaned nephews, who had come under her care.

"It's a hard time the family's going through right now," she says. "This is certainly not what we wanted."

Juli Niemann, a financial analyst at Smith, Moore & Company, believes St. Louisans are especially prone to "affinity fraud" — getting fleeced by a member of one's country club or church.

"We're stuck in the high school mentality," she says. "Everybody wants to be popular in the group, talking about how smart they were to invest. And, there's a lot of trust here. A shocking amount."

Phil Rosemann does not look like a man who just got hosed out of millions. In a recent interview, the Nevada resident assumes a relaxed demeanor, with pouches under his metallic blue eyes and the goatee of a man younger than his 63 years.

"This devastated me, but I can make more money," says the manufacturing consultant. "Some of these people are old. They had their life savings in this."

Rosemann made his fortune from his family company, Roto-Die, which creates mass-packaging machinery. His father launched the business out of a garage in Kirkwood decades ago, and by the time the family sold it off in the '90s, it had well over half the world market.

Rosemann was looking for something to do with the proceeds and met Sigillito through a friend. "He was an interesting guy," says Rosemann. "He speaks a lot of languages, was a world traveler, and it sounded like a big return for not a lot of risk." Ten contracts and a few years later, he was in it for $15 million.

The trouble started in late 2009, when Rosemann needed some of his investment back to finance a condominium project in Valley Park. Sigillito came up with some money but said Smith, his British associate, couldn't part with any more.

Fed up, Rosemann gave Smith an ultimatum, which came and went, then filed suit against the Brit in federal court on March 22, 2010.

On April 7, Sigillito e-mailed Rosemann's attorney, Sebastian Rucci, claiming he was desperately trying to refinance the Englishman's debt. But, Sigillito warned, his efforts were in "great jeopardy because of this litigation that now appears on the public record." Later that same day, Sigillito repeated emphatically that the suit "will do nothing but delay getting money in our friend's hands. Please....there is a great deal to lose."

In response, Rucci requested all documents relating to Rosemann's funds. Mike Becker, who was hired by Sigillito in a tangential matter but kept tabs on the English program, wrote to Rucci advising patience: "I have dealt with a lot of people in distress and although no expert of foreign investment [sic], have high confidence in my Midwestern abilities to smell a skunk."

For his part, Sigillito blamed the various delays on the tax season, the incompetence of his associates or overseas travel.

To allay Rosemann's fears that Sigillito was not taking his concerns seriously, the bishop wrote: "Please keep in mind that my family and I are deeply involved in this program, too. My mother (who is in her 80's) depends upon this program for much of her living."

Rosemann wanted to know: What if Smith was mismanaging things?

"Your fear that assets might be moved or hidden is unfounded," Sigillito wrote. "Mr. Smith is, as guarantor, already 'on the hook' as an individual, not just a corporate borrower. He would not commit fraud."

But with just a little bit of digging, Rosemann's attorney Rucci uncovered gaping discrepancies between the bishop's promises and reality on the ground.

Rucci hired UK-based lawyer Irvinder Bakshi to be his eyes and ears in England. On May 5, Bakshi drove out to Hinton Grange hotel, the "romantic getaway" near Bath.

There, she met Derek Smith, the real estate developer behind Sigillito's program who was supposed to be flush with millions in American loans.

Instead, she found a man with precious few assets. Smith owned the hotel, sure enough, but two other hotels listed as his in the due diligence memos were actually in receivership, Bakshi reports. The development company he owned — Distinctive Properties, Ltd. — had never traded. Smith himself told Bakshi he'd remortgaged his house three times to keep things going.

Smith also acknowledged that the Little Farm Nursery — which Vogel personally visited and called "active," and which Baer referred to as "income-producing" — was nothing more than a few derelict buildings. Smith confessed it hadn't made any money since about 2005.

Worse still: He didn't even own it. He only owned the option on it, for which he paid a paltry $7,500.

In a phone interview with the RFT, Bakshi calls this a simple yet profound accounting flaw, paraphrasing it this way: "Basically you're telling me, 'Lend me money against my farm,' and you don't even own the farm."

Bakshi inquired where the millions in American loans had gone. Smith had signed the agreements, hadn't he? Well, yes and no, Smith replied. He said he did sign stacks of papers, but any contracts would've been collated back in the United States. He had no copies.

"He seemed rather calm and unemotional," Bakshi says. "I would not, in his shoes, have been so calm. I would've expected him to have more knowledge than he did."

Bakshi noticed something troubling about the loan agreements. "If you sign a bunch of documents, it's highly unlikely that your signature will start at the same exact position on the page," says Bakshi. "Some of them look as though they were photocopies."

Smith would later confirm just that in an e-mail to Rucci: "I am in the ludicrous situation of having foolishly signed batches of signature last pages of agreements, with little or no knowledge of who [the] lenders were, or in fact what amounts were being borrowed."

Then, three days after this meeting, came the real shocker.

Rucci finally received a full accounting of what happened with Phil Rosemann's money on May 8. According to Sigillito's own records, Derek Smith — held out as the shrewd man behind the curtain — had only received $910,000 from all American investors combined since 2003, and only spent $186,000 on options.

Of Phil Rosemann's $15 million investment, Sigillito kept $2.6 million of it for himself, the document shows.

On May 13, Becker wrote to Vogel: "Paul, as I said to Marty earlier, the wolves are at the door but not in the house. Rosemann is not the only wolf but he is the biggest and he is moving faster and more aggressively then the others but make no mistake, they are coming too."

He continued: "You both need to keep in mind that Rosemann and Rucci believe this is a scam.... I know these are hard words but I need to make sure everyone understands."

Rucci was sure he understood perfectly. The actions of Sigillito and Vogel, he wrote, constituted "an international fraud that would shock even Charles Ponzie.... You have acted with gross self-interest." He filed a racketeering complaint on behalf of Rosemann and dozens of other investors on June 30.

In an interview with the RFT, Sigillito's local attorney, David Helfrey, denies that the program was a Ponzi scheme from inception. Asked why all the American lenders Sigillito had recruited were no longer receiving interest checks, Helfrey said only, "That's something you need to ask the person they loaned money to, Derek Smith."

Reached by phone in England, Derek Smith had little to say. "I don't know what's happening in the States," he said. "I know there's an FBI investigation, but I'm being kept at arm's length, and I can't comment."

Rucci, spearheading the civil suit on behalf of dozens of investors, believes that everyone was duped by Sigillito — even, to some extent, Derek Smith.

"Not only did Marty bamboozle the victims," Rucci says. "He bamboozled the co-defendants. That's how good he was."

Last spring Hal Millsap of Springdale, Arkansas, decided he'd had enough evasions. It was time to confront Martin Sigillito in person.

"Marty had been asking me to go out and raise some money because notes were coming due," Millsap recalls over the phone in a rural drawl, between drags of a cigarette. He'd personally put in $87,000 and convinced other Arkansans to fork over millions, receiving up to 5 percent commission.

But then Millsap grew suspicious. He refused Sigillito's request to find new lenders. "I smelled dirty diapers," says the 66-year-old insurance salesman. "That's when I decided to go up and have an eyeball-to-eyeball with him."

Millsap and a companion drove up to St. Louis. As was his wont, Sigillito took them out to lunch at the Racquet Club.

"He made a big point to call everybody by name, and they all knew him," Millsap recalls, adding that Sigillito insisted on showing them a plaque commemorating his grandfather's contribution to Charles Lindbergh's historic transatlantic flight. "I went, 'Yeah, well, OK, let's talk business.'"

And Sigillito did, reassuring them that all was well, thanks to a new commitment: A group of Palestinians was willing to pump $5 to $15 million into the program. Sigillito flourished a document to prove it.

"After two hours of talking," Millsap reports, "we climbed back in the car to drive home to Arkansas, and the first thing my friend told me was, 'That guy's blowing smoke up somebody's ass.' And I said, 'OK, that's my impression too.'"

The next day, Millsap got an unexpected call. It was Sigillito's long-time secretary, Liz Stajduhar.

"She was nervous and said something wasn't right," Millsap says. They conferred and decided the Palestinian document was phony. "Then she started calling me darn near every day. I told her to start making copies and find an attorney."

On May 17, after concluding once and for all that the program was a scam, Stajduhar finally heeded Millsap's advice. She arranged to meet with an old friend, attorney Ethan Corlija, who's perhaps best known for representing notorious kidnapper and child molester Michael Devlin in 2007.

At a meeting in Corlija's Clayton office late that evening, Stajduhar told her story.

Then the pair drove a couple blocks east to Sigillito's office.

"It was absolutely disgusting," says Corlija. Mountains of documents were stacked everywhere. There were even small piles of Sigillito's fingernail clippings here and there. "You would only believe it if you saw it. I was amazed."

The very next morning, Corlija says, he told the secretary's story to federal agents at the Bell Center coffee shop downtown. He passed along what she'd provided: a bulging file folder and digital copies of e-mails, thousands of documents in all. The agents immediately arranged a sit-down for the following day with the U.S. Attorney.

On May 19, Stajduhar and her legal counsel took an elevator to the 20th floor of the Thomas F. Eagleton Courthouse and were offered a deal: If she spilled her guts, and if everything she said was true and complete, the government would not use any of it against her.

Not necessary, Corlija told them. "I was so confident in my client's innocence, I said I didn't even want a proffered agreement in place," Corlija remembers.

What followed, he says, was a five-hour "marathon" Q&A session in which Stajduhar answered question after question accurately from memory.

"The thing about Liz," Corlija says, "is that she was a great record keeper. And she remembers everything."

It was decided right then: She would head over to FBI headquarters, get fitted for a wire and then confront Sigillito upon his return the following week.

Driving to work on the morning of May 24 with the wire in her pocket, Stajduhar prayed over and over, "God, please help me do this right." When she arrived at the Clayton building, she had to pause in the stairwell to collect herself.

Entering the office at last, she was surprised to see a dozen FBI agents already inside. They'd altered their strategy at the last minute and swooped in. Sigillito, weirdly, was seated at Stajduhar's desk, already under interrogation.

"He was so fidgety and anxious," she says. "They let him go but asked me to stay. He didn't know what was going on."

In late January Lynn Ann Vogel opened an e-mail from a stranger saying he'd lent money to Sigillito. When he stopped getting interest checks, he decided to contact her. After all, she was listed on the loan agreement as his legal counsel.

As Lynn Ann Vogel would later testify under oath, she notified her husband, Paul, who flipped through his files. He discovered that for over a year, Sigillito had been slapping her name on lenders' contracts without the couple's knowledge. Three more similar e-mails eventually trickled in.

One of those lenders filed suit against Sigillito in the 22nd Circuit Court on May 26. The plaintiff is known only to the court as Jane Doe. Although she's suing the bishop, so far her attorney, Ted Frapolli, has spent a significant chunk of time grilling the Vogels.

Frapolli deposed the couple on June 21. Paul said he confronted Sigillito about the contracts in January, demanding that he quit using Lynn Ann's name. But beyond that, the Vogels admitted, neither of them notified the lenders or reported Sigillito to the Missouri Bar Association.

Said Paul Vogel of the contracts: "I just stuck them in a file."

The day after their depositions, the Vogels sued Marty Sigillito, complaining that he attached their names to loan agreements without their knowledge or consent.

Dudley McCarter, the Vogels' attorney, says the proof of their innocence lies in the document's shoddy details.

For example, the Vogels are referred to in the documents with the British legal term "solicitors." Yet both are simply licensed Missouri lawyers. "Sigillito had all these references in there to the laws of England and the United Kingdom, which neither Paul nor Lynn Ann know anything about," McCarter says.

Furthermore, McCarter insists, his clients would never affix their names to contracts so riddled with errors. He points to one loan agreement containing odd phrases such as "remedies which July be available" and "any disputes which July arise."

What happened, McCarter believes, was this: Sigillito wished to quickly modify an agreement from the month of May to July. To avoid the tedium of switching "May" to "July" in each instance, he used a word-processing program to change them all at once. That changed phrases such as "remedies may arise" into "remedies July arise."

The amount of money being secured with such a sloppy contract? Only $35,000.

Now the e-mails are pouring in, McCarter says. In the past month, the Vogels have received dozens from passing acquaintances, as well as people they never knew existed.

"Marty used their name and reputation and took advantage of their friendship," McCarter says. "They're angry, sad, shocked, disappointed. I don't know how many words I can use to describe what they're feeling."

Helfrey, Sigillito's legal counsel, declined comment on the matter.

Paul Vogel did make some money out of Sigillito's program. He has testified that he recruited friends, family and clients to invest more than $3 million. This earned him somewhere between $125,000 and $150,000 in finder's fees, which he says he made no attempt to hide.

Yet Vogel, his wife, his father and his mother-in-law invested much more than that — a combined $590,000. Only his mother-in-law ever received any interest payments. Nobody got the principal back.

Vogel says he only authorized his former friend from the Racquet Club to circulate his due diligence report under two conditions: that Sigillito inform the clients that they needed to do their own research and that Vogel was not their attorney.

"Sigillito gave that memo out to people exactly contrary to Paul's direction," says McCarter.

Vogel was asked, when deposed, if he took any steps while in England to verify if Derek Smith actually owned the land he was claimed to.

"Other than visiting the properties," he responded, "no."

But how could he not notice that Little Farm Nursery was abandoned? McCarter suspects the executive was shown a distant corner of the ten-acre property, far from the vacant structures. Sigillito and Smith also provided papers indicating the rezoning had come through.

"A lot of people who know Paul Vogel believe in him, and they don't think he would intentionally do something like this," says Rucci.

He continues: "I would tend to agree. But you gotta ask yourself: What was he doing over in England? It's possible he was misled. But he obviously wasn't asking the right questions."

Bill Gaylor of Ohio is having trouble sleeping. The 84-year-old former manufacturing representative stopped getting his monthly interest checks last winter. Now, he fears he's lost the $250,000 — the bulk of his retirement — he handed over to Sigillito.

"'Devastating' is a pretty good word," says Gaylor, a World War II veteran. "It's got me pretty nervous."

Leonard Roman, also of Ohio, was a supervisor at a rubber plant when he broke his back on the job two years ago. He had to resign on disability. He took his life savings and invested with Sigillito. Last December, he tried to pull out some of the principal. Since then, he's gotten nowhere.

"I can hobble around a little; I use a cane," says the 57-year-old. "But if something else happens to me, I'll be in bad shape."

Stan Kuhlo of St. Charles inherited money when his parents died. He invested it with Sigillito. That, he now realizes, was a mistake. "Your parents work all their life, and you give it to somebody, and they steal it from you," he says. "That hurts. The guy really doesn't know how he affects a family."

Martin T. Sigillito is now facing three separate lawsuits. It's unclear from the documents available to the RFT where the millions transferred to Sigillito have gone.

Both the FBI and the U.S. Attorney's Office refused to comment for this story.

"What irritates me is that Marty's out there walking the streets," says Phil Rosemann, who may have been Sigillito's biggest investor. "Of course, it's hard for me to feel anything but stupid."

Correction published 5/1/12: In the original version of this story, we erroneously stated that R.C. Baer is a member of the family that co-founded the Stix, Baer and Fuller department store chain (acquired by Dillard's in 1984). Baer, who declined to comment for this story in 2010, acknowledges that there may some distant connection but says neither his family nor the department-store heirs consider themselves to be related.