On the morning of Saturday, January 7, people pack into the Best Place Event Center on Martin Luther King Drive to grab flyers and other promotional materials and listen to a training seminar on how to better canvass the city in support of their chosen candidate for mayor, Jeffrey Boyd.

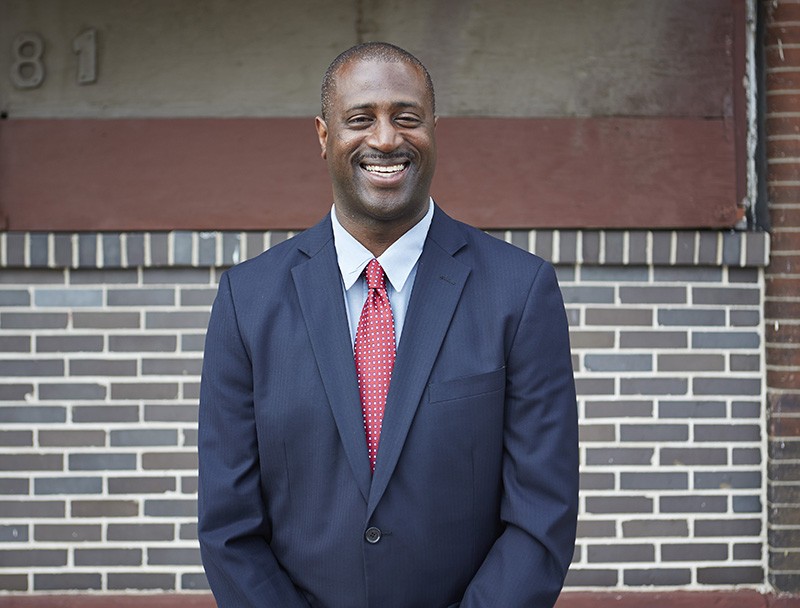

For the past fourteen years, Boyd, 53, has been the alderman representing one of the toughest neighborhoods in St. Louis, the 22nd Ward — an area that occupies a section of Martin Luther King Drive between Kienlen Avenue and Union Boulevard. He knows exactly how tough it is from first-hand experience: He and his family live there.

A graduate of Northwest High School, Boyd grew up in the ward before beginning a career in the army as a supply sergeant and logistics instructor. In his childhood, the 22nd Ward was considered a shopping mecca. But when he returned to St. Louis to start a family, the neighborhood had deteriorated into a morass of crime and abandoned property. He was bewildered by the changes, but determined to make a difference.

See also: Profiles of all five leading candidates for mayor

While ward residents appear to be on board with his mayoral run, he's definitely a long shot. Amidst the crowded field, both Lewis Reed and Tishaura Jones have already won city-wide races, while the presumed frontrunner Lyda Krewson, the alderwoman representing the affluent Central West End, has $403,000 on hand, according to the Missouri Ethics Commission. Even Boyd's fellow north-side alderman, Antonio French, has a national profile and 137,000 Twitter followers, due in large part to his activism during Ferguson.

As for Boyd, his brief moment in the spotlight beyond the borders of his ward came in the summer of 2015 after his 23-year-old nephew Rashad Farmer was shot and killed in Boyd's own district. In KMOV B-roll footage that went viral, Boyd let loose for three and a half minutes, making a desperate plea for people to put down their weapons and railing against young people killing each other in the streets and a disinterested city not doing enough to curb the devastation.

"I was pretty frustrated with the whole Ferguson experience, the police shooting experiences, and then I started thinking, 'Why me? Why did this happen to me? To my family?'" he recounts today. "So now it really hurts. 'Cause you see it happening time and again and you feel so sorry for people who've lost their family members, but now it's your turn. This ain't right. It ain't fair. I just had to speak the truth."

When he saw the clip online a week later for the first time, Boyd says he was surprised by his own outrage. But he was even more surprised at the response, as the video quickly amassed more than 2 million views.

"I got calls from people all across the country — law enforcement, FBI agents, people who just wanted to offer condolences, local people who wanted to help — it was extremely overwhelming," he says.

And though the clip garnered thousands of positive comments, there was negative feedback as well. Some progressives felt Boyd's comments unfairly blamed the youth who resort to violence rather than focusing on the poverty and lack of opportunity driving their recklessness.

But Boyd isn't here to run a popularity contest. "I'm tired of excuses. Dammit, let's all come together and do something about it. We just talk about it, we talk around it for too long. You have to first seek to understand where people are coming from before you judge them."

What Boyd lacks in name recognition, he makes up for in community outreach. He asks that voters examine his extensive record in public service. "I love service, I love helping people, it's part of my value system. I don't have to live in this neighborhood, but if all the good people leave, where's the hope for those left behind? I want people to feel hopeful about our community and that's why I work so hard to make a difference."

He points to positive changes he's brought to the ward, including the renovation of Arlington Grove School into new apartments and modern streetlamps along MLK Drive. But Boyd says there's still much work to be done. "I have a vision for this city to develop a community where everybody has an opportunity, where people can excel," he says. "Imagine St. Louis five to ten years from now, where all the vacant lots and buildings we see today all have new housing and businesses. We need leadership that's going to embrace rebranding our city. It's time for us to stop reacting to developers' plans and start making developers react to our plans. That is how a city grows."

In addition to increasing the size of the staff of the city planning department and making sure TIF incentives are being applied appropriately, Boyd also wants to upgrade police and emergency services. "We need to make sure our police department reflects the diversity of our community, that we have better community engagement and start looking for progressive strategies that will help us heal as a city. Bridge that divide that we have," he says. "We're only as great as our weakest neighborhood. And we have to put all that together, in a way that reduces crime. Everyone has value and we have to make every young person out here feel like they have value and their opinion matters and give them hope. I want to be a mayor that inspires people."

That kind of blanket inspiration may come at a cost, as Boyd has earned a reputation for being a compromiser in a political climate that seems increasingly unwilling to bend on key issues. But where some see grey area, Boyd sees opportunity. "People have accused me of being too close to Mayor Slay, saying he's a racist, and I'm like, 'That man is the mayor. I need his help and I'm going to get it.'" Not even the new reality of a Republican-dominated state government seems to throw a shadow on his plans. "Public service is party neutral. If I'm mayor, my expectation is that I build a relationship with Governor Greitens. He's a Navy Seal, a military guy — I think we share some common values and he's someone I can talk with," he says.

In the mean time, Boyd is enthusiastic to attempt a run for city mayor and show St. Louis voters what he's capable of. "My job as mayor is to convince people that the city has a vision of success that will make us better than we are today. And if we're always looking forward to being better tomorrow than we are today, then we'll be successful. We'll rise and create a better city."