As he waits to face his victims, the former youth minister can do nothing but stare at his manacled hands. His piercing blue eyes barely move as St. Louis County Circuit Judge Robert Cohen adjudicates some half-dozen criminal cases — heroin possession, burglary, probation violations. An hour passes before Brandon Milburn's name is called.

Milburn's case is left for last. From the back of the courtroom, nineteen pairs of eyes turn to prosecutor Michael Hayes as he begins his argument for the stiffest possible sentence.

The date is March 30, 2015: two months since Milburn pleaded guilty to molesting two eleven-year-old boys; fourteen months since Milburn's arrest; ten years since Milburn first set foot in St. Louis.

"Your Honor," Hayes begins, "Mr. Milburn has plead guilty to the seven counts of statutory sodomy, first degree. These seven counts represent a pattern of abuse that took place over a period of years, from the summer of 2007 till the spring of 2009. The defendant had ingratiated himself with the victims' families and with the church that they all participated in."

And Milburn's pattern of abuse began even before that.

According to Hayes, the state had received information about three other victims in Milburn's hometown of Louisville, Kentucky. Those molestations date back to 2000, when Milburn was in his early teens and the three boys in preschool. Hayes tells the judge that these earlier abuses spanned at least six years.

As Hayes speaks, Milburn's bald head droops toward his lap. His expression is blank.

"This is a pattern that has been going on for ten years," Hayes says. "We know there are other victims here in St. Louis, at least one who has been named."

There is more. Hayes cites a former staff member at First Christian Church of Florissant, or FCCF, the 2,500-member north-county megachurch where Milburn worked as an intern and volunteer on and off between 2005 to 2012. The staffer claimed Milburn showed pornography to some students and exposed himself to others.

"Your Honor, again, he used his position as a youth minster to gain access to all these different victims," continues Hayes. "In the sentencing advisory report, the defendant minimizes his activities, his offenses against the boys in this case, and actually denies there are other victims."

Hayes calls Milburn a predator, a pedophile who would reoffend if given the opportunity.

"For that reason, Your Honor, we believe a life sentence is appropriate in this case."

Hayes sits down. The two victims, now college freshmen, walk to the dais to address the judge. (Riverfront Times has changed their names, and those of their families, to protect their identities.)

"I stand before you a confused and hurt individual," says Adam Krauss, who first met Milburn through FCCF's children's ministry when he was in middle school. "Brandon Milburn was a guy I thought I could look up to and trust. He played as significant role in my spiritual life. He baptized me... He is a pathetic excuse for a man. He is a liar and a manipulator."

Next up is Harris Anderson: His family allowed Milburn to live in its house for several months in 2007. Anderson, too, met Milburn through his family's connection to FCCF.

"I kept the secret of what happened to me for seven years, seven very long years," he says, his voice shaking. "Your Honor, Brandon Milburn's effects on my life reach far past the sexual abuses of years ago. It seeps into my daily life even now. His actions broke my confidence, pride and trust."

The two boys' parents take turns begging for consecutive sentences on each of the seven counts, what would amount to a true life sentence.

Then several people speak on Milburn's behalf. One is a Los Angeles firefighter who met Milburn through Real Life Church in Southern California, and who flew to St. Louis for the sentencing. He describes how Milburn spent many nights in his own home, around his children. He insists Milburn is a changed man.

"I do not believe he is a predator," he says. "I love Brandon; my children love Brandon. If Brandon was released today, he would be welcome to come and live in my home."

Finally, it's Milburn's turn to speak.

"For over a year now, I've sat in my cell wondering what I would possibly say in this opportunity when it presented itself," he says. "I continue to be a believer and follower of the one true God, so I know the importance of confession and taking responsibility for my actions, as well as seeking forgiveness. For that I truly am thankful for this platform I've been given to finally express my heart. With your permission, I would like to turn and direct my statement to the families..."

Milburn spins 180 degrees to face the rear of the courtroom.

"No, no, no, no," whispers Anderson's younger sister. She shakes her head violently.

A middle-aged woman, a victims' advocate with the prosecuting attorney's office, leaps to her feet. "They don't want that, judge."

"Well," Judge Cohen says, "he can say what he wants, but if they don't want to hear it..."

Harris Anderson, a thinly built eighteen-year-old with glasses and a preppy haircut, slams his hands onto this thighs, jolts from his seat and strides to the courtroom door. He batters it open with both arms, barely slowing, and is followed by his parents and the Krauss family.

In seconds, Milburn is left staring at two empty benches. His shoulders slump, and he slowly turns back to Cohen. In a voice barely higher than a trembling whisper, he continues his speech.

"To the families I betrayed.... With everything I am, I'm so sorry. I would do anything to take my childish behavior back.... I know that I sinned against God and that I sinned against them. I was given a position of trust, and I abused it on them.... My actions have haunted me for years.... I truly hate what I've done. I'm sorry, God, I'm so sorry."

Between sobs, Milburn thanks the handful of supporters who spoke on his behalf. Then he delivers his final plea to Cohen.

"I'm ready to be put this all behind me and to continue reaching for my dreams of filmmaking and in music. ... Your Honor, I ask for your mercy in your decision today, for a chance to further prove who I am."

As Milburn returns to his seat, Dawn Varvil's face contorts itself in a mask of bitterness and grief. Varvil had once counted Milburn as a friend, a trusted partner in ministry and youth outreach. Like others who knew and worked with him, she was once enamored with Millburn: his powerful preaching, his boundless creativity, his single-minded devotion to children in need. Now, she can only see the lies. As Cohen announces Milburn's sentence — 25 years, to be served concurrently on each of the seven counts — tears stream down her cheeks.

But there will be no closure for Milburn's victims, and none for Varvil. And none, for that matter, for the members and leadership of First Christian Church of Florissant.

Today, more than a month after Milburn's sentencing, Varvil is at the center of a controversy that threatens to tear the 58-year-old church apart at the seams. At play are dueling narratives from Varvil and senior pastor Steve Wingfield: Wingfield maintains he knew nothing of Milburn's monstrous secret life until his 2014 arrest. Varvil insists that's not true, and that she personally told the pastor about Milburn exposing himself to five boys and sleeping in bed with a fourteen-year-old boy.

Wingfield says Varvil is a liar — and he's seeking a court order to force her to recant the claims about the 2012 meeting. Filed April 16, the lawsuit also seeks at least $25,000 in damages.

Now one of the largest churches in north St. Louis County is in crisis. And for atonement for Milburn's sins, Varvil and a growing coalition of former members, dissenters and abuse survivors want accountability from Wingfield, a man they've come to see as a calculated and self-serving manipulator. Some want nothing less than Wingfield's resignation.

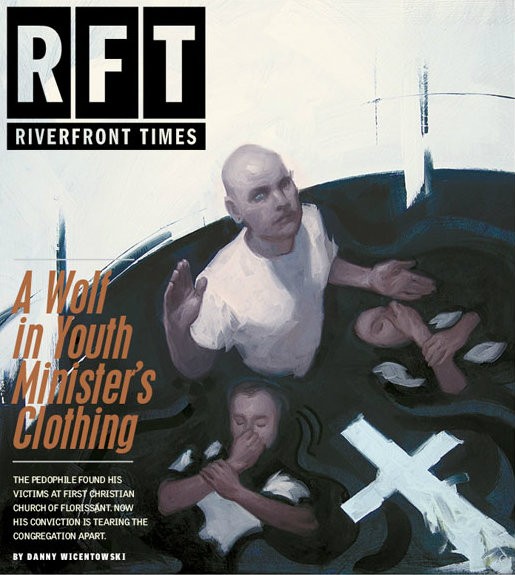

Brandon Milburn, they say, wasn't just a lone wolf in minister's clothing. He was enabled and supported by church leadership even after others made their concerns clear.

"Distancing yourself may be the safe thing to do, but it is morally wrong and a failure of Steve's and the rest of the elders' leadership. It was also against the law," a former FCCF minister named Titus Benton wrote in a letter to the board of elders in February. "There is so much that has happened that remains a secret, and that is not acceptable.

"There are people who are suffering and...look at the church as a co-conspirator instead of an agency of healing."