The United Nations isn't the only place where Jewish-Muslim tensions have escalated this week. On the campus of Washington University, a small imbroglio over an advertisement placed in the student newspaper has generated quite a buzz.

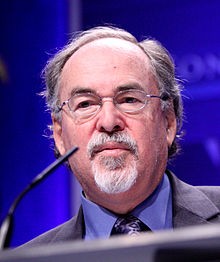

The dust-up began Monday, when the print edition of Wash. U.'s Student Life included a full-page ad placed by the David Horowitz Freedom Center, a right-wing Zionist organization based in California that has placed similar types of ads in college newspapers across the country.

The ad in question was emblazoned with the headline: "The Palestinians' Case Against Israel Is Based on a Genocidal Lie." Students across religious and ethnic lines took offense, calling it false and malicious. After holding a meeting last night, some are lashing out at the editors of the student newspaper.

"This racist, slanderous speech has no place on our campus," Sarah Rangwala, a 21-year-old senior, tells Daily RFT. "The ad made generalized statements about Arabs that had no factual basis whatsoever."

Among its various statements, the paid advertisement declared that Palestine has never existed as a state, and that Palestinians are to blame for the Palestine-Israel conflict. (See it on page 13 here.)

Rangwala, who is Muslim, helped organized last night's meeting, which was held inside the university student center. About 30 people attended, including representatives from the Association of Black Students and J Street, a national Jewish student organization that promotes peace in Israel and Palestine. Most of the attendees were angered by the ad. But a handful of students acknowledged its First Amendment justifications.

Rangwala and her associates say they plan to collect signatures and deliver a petition to the university administration and Student Life, in hopes that a policy is created so that similar ads do not appear in the future.

Michelle Merlin, 21, the editor of Student Life, defends her paper's policy. "This is something we never would have run in editorial pages," she says. "This was an ad. I'm not going to start sending political messages through ads." She notes that her paper has run pro- and anti-abortions ads in the past, and that the university has hosted many controversial speakers on campus before, including Horowitz, in 2005.

Horowitz is no stranger to controversy. The conservative author has made frequent visits to college audiences, delivering speeches slamming Islamist fundamentalism. In 2007, he christened a movement called "Islamo-Fascism Awareness Week." His agitating proclamations have incited the rancor not only of Muslims, but of blacks, feminists and college professors as well. In 2006, Saint Louis University canceled a previously scheduled Horowitz appearance.

The question at Wash. U., though, is not so much the truth (or lack thereof) behind Horowitz's views, but whether or not the editors of Student Life made the right decision to run the ad. And both parties seem to agree -- the question is not so much a legal one as much as an ethical one.

By labeling the full-page display as an advertisement -- and taking the extra step of running a disclaimer on a separate page acknowledging that the ad was likely to cause controversy -- the editors made clear efforts to ward off any libel controversy. The landmark U.S. Supreme Court case in 1960, New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, determined that a news publication cannot be sued for running a libelous ad, so long as it wasn't run with reckless disregard for the truth. The Horowitz ad didn't defame any individual person by name, so the editors seem to be on solid legal footing.

But just because you have a right to do something doesn't make it right to do so, say the angry students.

In an Op-Ed submission to Student Life, representatives of two of Wash. U.'s Jewish student groups denounced the ad. The newspaper's editors, they wrote, "chose to import a radical opinion on the conflict from outside our community. This demonstrates that StudLife attempted to create a controversy where none had previously existed. It is our position that, from a journalistic perspective, it should be the task of a newspaper to report on controversy rather than manufacture it."

Merlin stands her ground. "This isn't an opinion that hasn't been expressed before," she says. She did, however, choose to run the disclaimer because she wanted people to know that the editorial staff didn't necessarily agree with it.