The screech of an emergency alert buzzer summons students to the video broadcast. "The bodies of the dead are returning to life," the ticker announces, just before clips of world leaders, scientists and news anchors frantically explain that hundreds of millions of people may die after being exposed to a virus thanks to a laboratory mishap in San Francisco.

Soundbites come fast, as scenes of doctors rushing through packed medical facilities and military groups leading patients into detention zones splash across the students' iPad screens.

"Anyone showing signs of a contagious illness will receive special treatment here, at the airport's purpose-built quarantine center."

"The mandatory quarantines have sparked civil unrest."

"Containment is not very likely."

"Those who aren't killed by the virus will probably die in the fighting, so maybe this is it. This is how it ends. Pretty soon, there won't be anyone left."

The broadcast suddenly cuts to a newsroom, empty except for a desk where a man with bloody bandages around his head holds a script and prepares to read to the camera. Next to him, a woman in a patient gown is unconscious, her arms restricted by thick chains and her face covered by some sort of respiratory mask. Her lifeless body slumps over the desk.

"Hello, this is Dr. John Marino broadcasting on the emergency system," the man reads. "If you are a survivor, there's a safe zone established. It will be available Monday at 9 a.m. in Kernaghan 3136, Maryville campus." The video screen behind him shows b-roll of the military shooting chaotically at a horde of zombies surging into a fenced-in area.

Marino repeats the safe-zone instructions, adding, "Do all you can to survive." Then the broadcast abruptly cuts out, replaced with black-and-white snow.

And with that, eighteen Maryville University students are welcomed into HUM 297H: Are You The Walking Dead? — or, as it's better known on campus, "the Zombie Class."

The Outbreak

Despite being five years old, the Zombie Class has remained a big mystery on the Maryville campus — a secretive club whose inner workings are known only to students, class alumni and professors.

Sure, undergrads can find information about how the class might align with their interests or which core requirements it satisfies. "This course will use the thought experiment of the premise that the popular 'zombie apocalypse' has taken place," the syllabus promises. "Within that construct, students will examine their ideas about survival, ethics, quality of life, communication, core beliefs, and social mores. Parallels and discussions will be drawn to other times of crashed society constructs in history as a way of exploring human responses. When the zombie apocalypse happens, who are the walking dead?"

But the day-to-day occurrences? The projects that make some students scream, cry and nearly give up? The physical and mental tests of perseverance? What happens in zombieland stays in zombieland.

Until now, that is. With the Zombie Class in its final semester, professors Kyra Krakos and John Marino agreed to let in a journalist.

Krakos and Marino debuted the class in 2014 at Maryville, a private university in suburban Town and Country with about 2,700 undergrads. It seemed like a perfect time and place to focus on The Walking Dead, one of the biggest comic book and television titles in history.

In both mediums (launched in 2003 and 2010, respectively), the plot begins like this: Sheriff Rick Grimes is shot while on the job and ends up in a coma, waking in his hospital bed a month later to find that his facility — and city — are completely abandoned except for the ravenous undead. He begins a years-long journey that has him making hard decisions about humanity, community, government and survival.

And there's blood. Lots of blood.

It was against this backdrop that Krakos and Marino began exploring how to entice students to learn by employing an interdisciplinary gamification system wrapped up in pop-culture goodness. Educators have long tried to shake up teaching, with a variety of successful (and not-so-successful) methods to help students think critically and lean into their blossoming abilities and interests. Krakos and Marino combined that innovation with group competition and a direct hook to the sociological aspects of The Walking Dead. Adaptability. Information gathering. Identity. Traditions. Class. Rights. History. Ethics. Leadership. Justice. Survival. All of it, they decided, could be examined in a post-apocalyptic world that they and their students would build together.

They had students deconstruct novels and short stories about war, horror and exclusion, including The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas by Ursula K. Le Guin, Freedom Summer by Bruce Watson and Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read. They also assigned viewings of The Walking Dead. They examined Shane's dark turn, Carol's newfound strength, the Governor's horrific rise. They contemplated the lengths they might go to find food or protect their family members. They considered what to do with people who wouldn't play by a new society's rules.

Krakos and Marino make for an odd couple, academically speaking. Krakos is an assistant professor of biology — a scientist who studies evolution in plants, with a focus on pollination and conservation. She's a fast talker who gushes when she gets excited about a subject or sees that people are digging what she's saying. Marino, who specializes in the Arthurian grail legend in literature, is her temperamental opposite. The associate professor of English is more reserved, with a tendency to reflect on multiple subjects when asking questions or patiently explaining the genesis of an idea.

But both are sci-fi and fantasy aficionados, with bookshelves full of alien invasions and horror stories that center around one question: "What does it mean to be human?" Together, Krakos and Marino studied the worldbuilding within those classics and pulled together elements that would challenge students to think from every angle.

Their first Walking Dead class was a university seminar, a course for first-year students to acclimate to Maryville while intensely exploring an interesting topic in a small-group setting. They deliberately provided a light syllabus so as not to give away what students would encounter in the classroom: quarantine signs, crime tape and plastic body parts. On day one, guards in HAZMAT suits scanned students for "contaminants" before sorting them according to some unspoken code. It was the first indication that the class would be unsettling on more than one occasion.

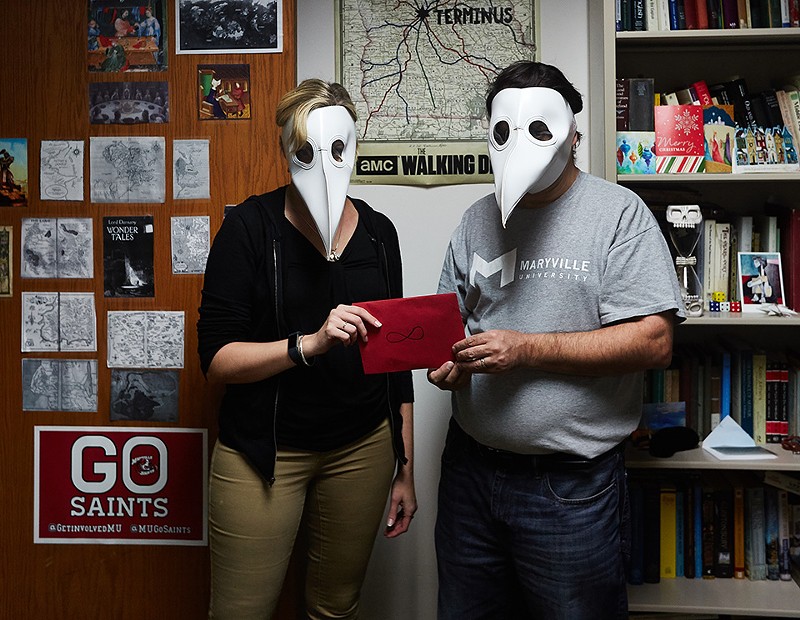

A red envelope graced with an infinity symbol contained each week's theme. "The zombie apocalypse is happening, so grab your group, pack a car and get out of town," the assignment might say.

And then, just as everyone began to settle in, the professors produced the red dice that would alter students' paths for the rest of the semester. Every week, chance threw a new wrench into survival plans.

*dice roll*

"Wait, you don't have a can opener for those green beans. Now what?"

*dice roll*

"Wait, there's no gas in your car. Can you explore the area and find some?"

*dice roll*

"Wait, one of your group members has been bitten. Will you try to heal his wounds or shoot him immediately?"

There were grumbles as students had to form new alliances and solve unexpected hitches on a regular basis. Assignments often went well beyond writing essays. One week, the students were challenged to consume only non-perishables and water for seven days, triggering particularly loud complaints. The professors assured students that the food challenge was safe and that bodies can quickly adapt to new feeding situations (introduced to the idea by a professor in grad school, Krakos had herself completed it). For the Maryville students — particularly athletes — who were used to eating several freshly prepared meals each day, surviving on canned green beans, peanut butter and condiments was a shock to the system, but it helped them think through their bodies' adjustments as well as the mental tests that a lack of adequate nutrients can create.

Gradually, the students understood that they were starting from scratch. Through their ever-changing teams — which often saw students "suffering" from ailments or even "dying" from zombie bites — they could move through a post-apocalyptic world and rebuild a new society, deciding to draw on what they know or trying a new direction. But to do so meaningfully, they had to consider who comes out on top, who gets left behind and how that connects to the United States today. It was an educational role-playing game on steroids.

"Just gamifying the class like that really gets them invested and involved in what's going on," Marino says. "We're putting them into a scenario that's fictional and trying to draw connections to the real world."

The element of surprise was key to fully absorbing all of the lessons, so at the end of the first semester the class was offered, the students swore an oath. They would never talk to anyone outside of the class about what they did. It was secret. Powerful.

As expected, that first class in 2014 drew students who already were into The Walking Dead or who assumed (wrongly) that a class about zombies would be one they could coast through. But in subsequent years, the mystery surrounding what Krakos and Marino had created became almost as enticing as the subject matter itself.

"As a student in the class, I had no clue what was going on," says Deanna Deterding, a senior environmental-science major who enrolled as a first-year student. "Every week was a surprise, so it was kind of intimidating and a little bit scary, because you're like, 'What are they going to do next?' All of the other seminars sounded interesting, but this one sounded really cool. I'd never taken a class like that — a zombie class."

Later, Deterding enjoyed reliving some of the stress of the experience as its teaching assistant. "I'm supposed to help the students, but in this class it's a little different because I can't give away what's going to happen next," she says. "So if students asked me about what would happen in the next week, I had to be like, 'Sorry, I'm under oath. I can't say anything.'"

Pleased with the initial class, Krakos and Marino applied for a Scholarship of Teaching and Learning grant to continue the class and study it as gamification. "Our 'gamified' setting is effective because we teach our students real-world science and challenge them to critically think in a role-played gamified setting to apply the principles of that science and communicate their choices by way of the reflective writing of the humanities — our truly cross-disciplinary methodology," Krakos and Marino wrote in their grant request. Awarded the money, they went on to offer the class as a seminar for four more years. It's now part of the Bascom Honors Program at Maryville, and this semester they are offering it for what they say will likely be the last time.

Even after five years, though, Krakos and Marino still have plenty of surprises in store for their students, including bringing back zombie alums to assist. "Once a zombie, always a zombie," Marino says with a grin.

The Herd

The students of HUM 297H gather in front of Reid Hall wearing mild looks of worry as they plop their backpacks onto red metal benches near a large swath of grass. It's Halloween — a gray, drizzly morning on campus — and they aren't sure what's in store.

The students are about halfway through the class, and they've already dealt with famine, disease and conflicting personalities both through reading and through unconventional real-life challenges. But today is even more unusual; today they have been told to meet outside. All Krakos and Marino suggested in recent days was to wear clothing that's easy to move around in. The students have obliged, arriving in hoodies, athletic pants and sneakers, but they can't help but wonder about ... well ... everything.

Krakos and Marino inspect a few mysterious bundles and chat quietly with each other before sending the students to the far end of the grass near Gander Hall. Krakos holds up a flag-football belt, one rubbery ear affixed to each of the two blue and green fabric strips flapping in the wind. "This is what you're trying to have survive," she says.

"Oh my God, nooooooo!" one girl shouts, understanding the game almost immediately.

Each person on a three- or four-member team — the same survival groups that the students have been in since a shake-up a few weeks ago — will wear belts with two ears as they hustle through a mass of zombie volunteers within a confined area. If the slow-moving zombies snatch an ear, it counts as a bite; the ears that make it to the other side will be added up as team points.

Over three rounds, the field becomes smaller, with the zombie population increasing to reflect the density of St. Louis, then New York City and finally Dubai. The question for the teams is whether they can make it through these "cities" with all members (and their ears) surviving, or whether they'll have to get creative and sacrifice friends for the good of the group — as characters have done on The Walking Dead.

"So where are my dead people?" Krakos asks. Students who had "died" during previous rolls of the mystery dice raise their hands. "Your ears don't count, but you do have to run through with them and they can count against you," Krakos tells them. "I know, I know. 'It's so unfair.'

"And where's the survivor with 'pneumonia'? Yeah, pneumonia left you with damaged lungs, so you can't run; you can only walk," Krakos continues as students grumble. "All of you, you can't hit the zombies. You can't hurt the zombies. You can't smack the zombies. You've just got to get through. Your entire grade is based on how many ears get to the other side."

Students look apprehensively at the small field, questioning whether they can dodge not only the volunteer zombies but also a few trees, a child-sized Disney tent and a wheeled plastic cart.

But the herd of zombies — made up of Zombie Class alumni as well as a psychology class -— is already starting to shuffle onto the grass. On Krakos' cue, they begin to groan hungrily.

Group one heads to the starting line and chats as Marino grins from the other end of the field. After Krakos gives the signal, the team of four jumps into the game area and tries to bolt around the hungry zombies. Ashley quickly loses both of her ears and "dies" as her teammates press ahead, somewhat stymied by the number of zombies within the narrow gauntlet.

Mady makes it through without being "bitten," while Reid and Madison each survive with one ear.

"I just tried to slip through as fast as I can and tried to push people with my shoulder so they couldn't grab my ears," Mady explains. "I guess it worked — I didn't lose any."

"I was just trying to go where people weren't," Reid adds.

The four other teams try their luck with varying degrees of success, with many teams running straight through or feigning to the side before zipping past the zombies the other way. With each attempt, the students think more carefully about strategy. One team forms an outward-facing circle and moves as a single unit. Another tries to ram the plastic cart through the zombie herd so that at least a few students have a chance at reaching safety.

After the professors condense the field to the smallest boundaries — about a twenty-foot square — a group even grabs the polyester tent, pulls it over their heads and tries to use it as a shield while running, only to collapse together when the zombies swarm.

"Every year, some group tries the tent thing, and it's always a cluster-disaster," Krakos whispers as students try to rebuild the smashed tent. "It always seems like a good idea to them, but you've got to think it through."

"We tried making a circle, we tried piggybacking," remembers Alison Riddle, a junior who took the class as a first-year and stopped by to watch the day's action. "The team that won my year had a kid in an electric wheelchair. Everybody hopped on and he put it on at full speed, and the zombies were worried about their toes, so they just got out of the way."

She adds, "I miss this a lot."

People are pushed. Boundaries are crossed. Risks are taken. Tents are broken. The final ear tally will have to wait until Krakos and Marino compare notes, but one thing is certain by day's end.

These students are survivors.

The Bite

Krakos and Marino put their students through the wringer over the course of the semester. Challenges to group dynamics. A seemingly impossible escape room. An in-class funeral.

But the week before Thanksgiving break, the students have a surprise of their own for Krakos and Marino. They've been studying leaders at times of war, examining their big speeches, thinking about their hard choices and comparing their actions to the slaughter, selfishness and even inspiration on The Walking Dead. And in HUM 297H's post-apocalyptic world, it's now time for the five teams to put forth their own plans for government and laws. It's time to rebuild society.

The professors have seen it all before. But this year, it's different.

As Krakos and Marino approach Kernaghan 3136, they find two male guards waiting for them outside the familiar "quarantine zone" door. They're dressed in head-to-toe black, wearing sunglasses and holding lacrosse sticks. Their expressions stony, the guards usher the professors into the dark classroom.

There, the rest of the students — clad in black like the guards — are standing in a circle. The guards point Krakos and Marino to two desks on opposite sides within the circle, a place setting and an envelope waiting for each of them.

(Krakos later explains just how thrilling the moment was: "We were giggling with excitement because, oh my gosh, it's everything we want from them, you know?")

The guards move to block the sightline between Krakos and Marino, and a student in the circle sternly orders, "No talking!" Another student takes notes on all activities as if he were a court reporter, deliberately avoiding eye contact with the professors.

The presentation begins. The five communities declare unification: They are now one settlement named Blagden, which means "dark valley." Based on aptitude tests, all members will participate in task groups that take care of Blagden's needs: security, agriculture, scavengers/weaponry, building and repair, scouting and health care. A council comprised of one representative from each task group will serve as the judiciary, preventing any single interest from rising above the others. Tuesday mass is required by law. Weekly medical checkups are mandatory. Blagden is peaceful, so the settlement will not go to war unless attacked first.

One more thing: Blagden is "situationally cannibalistic." The work of finding and preparing that food falls to the "agriculture" group.

People who stumble across Blagden will be captured and presented with two choices: join or be eaten. "Those who decide to join us will then be initiated into the society by eating human meat which will be presented in the form of people jerky. Those who refuse our society will be stored in a cell for later use," the presenters declare.

There's a long backstory about Blagden's first settlers cutting out and sacrificing their tongues as a vow of silence to a goat god named Adron in exchange for his protection and guidance. Today, the tongues of Blagden's prisoners are offered to Adron during Tuesday mass.

Marino is beaming.

"Will you join us for dinner?" the students ask. Krakos and Marino open their envelopes to find a bloody note with the same question.

On their plates: jerky. Symbolic human jerky.

"Well," Krakos says, looking again at Marino. "All hail Adron."

"I'm hungry!" Marino exclaims. Both pop their jerky into their mouths, signifying their acceptance of Blagden's rules.

Stoic during the entire presentation, the class now cracks up and turns on the lights, excited to tell their professors about how they planned everything and what they learned: where they found fake blood, how they learned that religion could keep people in line, how many times they used messaging and Reddit to communicate ideas, why they thought Marino would be more into Blagden's laws than Krakos.

"It's horrific and dark, and they're adding religion into the mix," Krakos explains later. "I looked at John, and he's got this big smile on his face because it's very Lord of the Rings."

Beyond that, though, the presentation shows how the class is living up to the professors' aims.

"We were so pleased because they were demonstrating all three of the goals of our class: communication, community, critical thinking. It's really hard to form a government. It's really hard to write a constitution," Krakos says. "This is exactly the kind of initiative and engagement we want. We are so proud of them."

But just as quickly as Blagden is formed, it has to end. This week, the final week of the semester, every student will open a red envelope and learn that they've been bitten by a zombie. They'll write personal statements — their own obituaries — and complete one last scavenger hunt that has layered meanings.

And then they will die.

The Oath

The eighteen students of the 2018 fall semester's HUM 297H are the last at Maryville to explore hands-on the implications of a zombie apocalypse, at least for now. With The Walking Dead in its ninth season, zombies are starting to lose their "it" status, and Krakos and Marino are ready to wind down their elaborate scholarly exercise.

That makes these students the last at Maryville to carry a manual can opener at all times, just in case. The last to dread the red envelope of death and disease. The last to be scanned for contaminants.

And during their final exam, they'll become the last to take the ceremonial oath of silence, vowing not to reveal the class' assignments, expectations or twists to anyone. "The first rule of zombie class: Don't talk about zombie class," class alumni insist. The eighteen students here are the last of the small, secret club. Sure, some tales will be passed around now that there are no more points to award. But not everything. Not the good stuff. Despite what's shared in this story, there are still class mysteries that even a reporter can't crack.

As for Krakos and Marino, they're hungry to create something new. They may explore world-building in another class with a different pop culture property as the hook, but for now they have no definite plans beyond presenting their zombie findings to other educators and getting back to their core biology and literature courses. And who knows? Entertainment is cyclical. Zombies might eventually make a comeback.

But today, it's time to drive the knife through the five-year-old zombie class's brain.

"Next fall is when it will really be hard. It's like a grief process," Krakos says. "I'm going to miss working that closely with John. He's two doors down from me and we'll always collaborate on things, but that intense partnership is such a treat. I didn't expect that we were going to world-build like that.

"We're going to miss our zombies. We really get close to these kids. But I also know that the worst thing you can do is stay too long at the fair with a concept," Krakos continues. "I've been a zombie professor for five years, and I love that title. I've really, really loved being a zombie professor."