Would anyone like to adopt the St. Louis County Pet Adoption Center?

It is about eight years old, filled with adorable animals, and its current owner, the county's Department of Public Health, is looking more and more like it doesn't want the hassle that comes with directing one of the largest open-admission animal shelters in the region.

Outside the low-slung building in Olivette, dog walkers crisscross the sidewalk on their way out of the shelter parking lot. The dogs strain on their leashes, noses to the ground, their legs set at eager angles as they use this brief time outside their kennels to investigate odd rags and interesting leaves.

In a typical month, the shelter takes in more than 300 animals. Staff members say the shelter often reaches double its effective capacity, but, until recently, officials and shelter board members defended the facility's operation by pointing to the only statistic that seemed to matter: the euthanasia rate.

In 2011, when the shelter opened, pounds were being phased out in favor of an animal control model that emphasized adoptions rather than the quick and fatal disposal of strays. At first, the shelter euthanized about half the animals in its care every year. But that rate was down to 22 percent by 2017. At the beginning of 2018, the rate hit single digits, a venerated benchmark in the animal welfare world that is often associated with "no kill" shelters.

It was a notable achievement — and it had political ramifications. Then-County Executive Steve Stenger had made the county's euthanasia rate a key issue in his 2014 election campaign. After he won, he moved the Animal Care & Control division under his office, adopting the shelter — and the credit for its plunging euthanasia rates — as his own.

And indeed, the euthanasia rate kept falling. Or, at least that is how it appeared.

The last two years have seen the shelter staggered by scandal. First, its once-heralded director was fired after she was accused of bullying staff and making racist comments. Her termination was followed by the release of an audit that exposed the misleading nature of the shelter's past euthanasia reporting.

Today, the shelter's celebrated, euthanasia-lowering successes have been revealed as a statistical sham. Stenger is in federal prison for separate crimes. The future of the department of Animal Care and Control is uncertain. The shelter is at a crossroads. All paths seem to pass through crisis.

Even in the shadow of scandals, multiple shelter employees who spoke to the Riverfront Times insist that hiring a competent director and stabilizing a staff that is fearful of losing jobs would make all the difference. Instead, the Department of Public Health is toying with the idea of ditching the whole mess through privatization of the shelter.

If that happens, it will not be without a fight over who is responsible for the dysfunction. In interviews with the Riverfront Times, employees, volunteers, and county officials offer clashing viewpoints of who deserves the most fault, with staff blaming county officials, volunteers blaming staff and county officials blaming both everyone and no one.

For all the finger-pointing, the question is: Where does the shelter go from here?

"We're the redheaded stepchild of the county," one shelter staff member tells RFT, summarizing the predicament. "No one wants us."

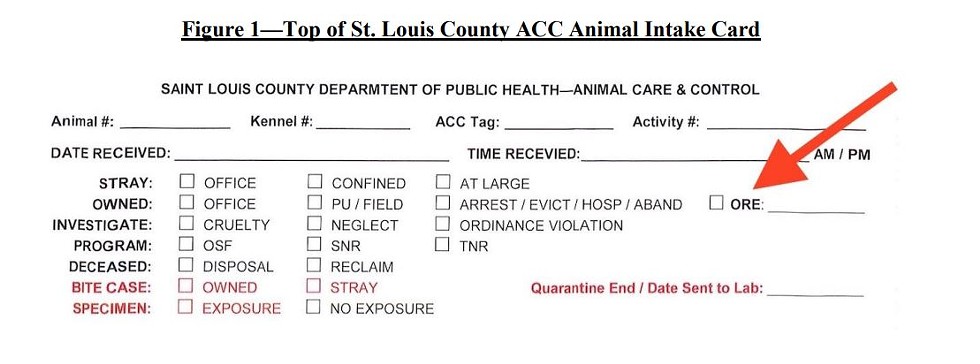

Three tiny letters — "ORE" — were the key to a statistical smokescreen that concealed the true numbers of animals killed at the St. Louis County Pet Adoption Center.

The letters appeared innocuously above one of the many boxes on the shelter's intake forms. Most people seemed to barely notice as they said their emotional goodbyes in 2018 to their suffering pets.

"I think 75 percent of the people who came in were not thinking straight," recalls one former shelter employee, who spoke to the Riverfront Times on condition of anonymity to describe his time as an intake worker.

"These were people upset about having to give up the dogs. They would sign whatever you asked them to sign."

But that one box, floating off on the right side of the page, was crucial. The staffer says a supervisor pointed the ORE box out to him during the training, specifically directing him, to "get them to initial this" during the intake process.

"I was being told about 30 different things that day," he says, "so I didn't question it."

He did get people, lots of people, to sign it.

Like other employees, though, the ORE proved impossible to ignore forever. It stood out even among the other issues, like the horrible rumors heard about the last director, Beth Vesco-Mock, who had been fired shortly before his hiring. The shelter had "chronic understaffing," he says, an obstacle made worse by a group of shelter volunteers who, in his view, "only wanted to complain."

"People were there because they loved animals, which was great," he recalls, and it was that force that united the shelter's factions, bonding them to an overriding goal: "To euthanize as few animals as possible."

As he'd later come to understand, though, that goal had twisted the shelter's intake procedures in strange ways. When he finally asked his supervisor about the ORE box, and why he was being pressured to get it signed in every intake, he wasn't prepared for the answer. He was informed that ORE meant "owner requested euthanasia."

"I wasn't thrilled about it," he says now. "Because they weren't all requesting it. I went to my supervisor, and she told me, 'Oh it's just a policy, you don't have to do it.' And I said, 'Are you sure?'"

There are conflicting accounts of how and when the shelter's ORE policy originated. At times, it seems it was applied inconsistently. A second shelter staff member, who worked in various departments since 2018, recounts that she knew of intake representatives who simply ignored the ORE requirement or allowed people to decline initialing the box.

"If someone really had a problem with signing the ORE, we were like, 'It's OK, you don't have to sign it,'" she says. "Because we can't force them to sign it."

They would be ordered, though, to try. After the firing of the shelter's director in March 2018, multiple employees tell RFT that the shelter's leadership, helmed in the interim by a Stenger policy advisor, continued to aggressively push the ORE policy. When intake representatives complained about the ORE to their supervisors, they were given a new directive.

"Our supervisors were saying, 'We have to do it. You do it or you lose your job.'"

It wasn't until July 2019 that an independent audit exposed the ORE policy for what it really was: a strange kind of fraud, one that obscured — and, in a way, laundered — the shelter euthanasia rate that was reported monthly to the county executive and shelter advisory board.

The ploy hinged on abusing the "ORE" intake category, one intended for animals whose age or medical conditions left only one option. Typically, ORE cases are rare: The audit, conducted by California-based Citygate Associates, surveyed 28 other government-run animal shelters across the country, and found that ORE cases made up just 2.8 percent of total outcomes. St. Louis County's animal shelter had five times that rate, with 14 percent of all animals passing through the front doors being marked for "owner requested euthanasia."

It was more than the shelter data that convinced auditors something was amiss. One dog, a husky mix designated for ORE at intake, "was surrendered by his owner on 1/16/19 due to a noise ordinance violation," and then euthanized after 27 days in the shelter, auditors found. Another ORE dog, a pit bull returned for being "disobedient," stayed in the shelter 55 days before being euthanized for "behavioral reasons."

In at least one case, the audit noted that a woman turning in a dog specifically asked that her dog would not be euthanized. "She checked and initialed the ORE box as directed by staff, but Citygate did not hear her being told what the ORE initials actually meant."

It was this category of animals — dogs and cats whom the shelter seemingly tried to adopt out, and then, failing that, moved to euthanize — which did not belong as ORE. That was critical: The shelter reported only its "shelter decision" euthanasias to its higher-ups. ORE cases, though, are not considered "shelter decision," and so became the shelter's statistical dumping ground.

The ORE scheme was brilliantly effective. The audit found that while the shelter reported 602 "shelter decision" euthanasias to its advisory board in 2018, its ORE euthanasias had climbed to 645 cases — in other words, the majority of the shelter's euthanasias that year.

Some staff members complained, while others put their head down, fearful of making waves.

"That was why the policy was put in place, so it didn't look like you'd done euthanasias," the former intake staffer says. "Their desire to keep animals from being euthanized, which is a good desire, was taken to very odd extremes."