In the dim gray dawn of Sunday, April 25, on the southern outskirts of Cahokia, Illinois, a pickup truck was creeping along the Prairie du Pont Creek levee and stopped. Behind the wheel, Bob Shipley of the Metro East Levee District was supposed to be checking the creek's water level. Instead, he found himself staring down at an obsolete railroad bridge that crossed the dark, treeless expanse. The body of an African American boy was dangling from one of the wooden bridge supports.

"I thought maybe it was a hoax," Shipley recalls. "I couldn't believe it at first."

It was just after 7:30 a.m. when he dialed 911. Shipley chose to stay in the truck. An hour later police officers, an ambulance and a deputy coroner from St. Clair County had all arrived. Evidence photos were taken.

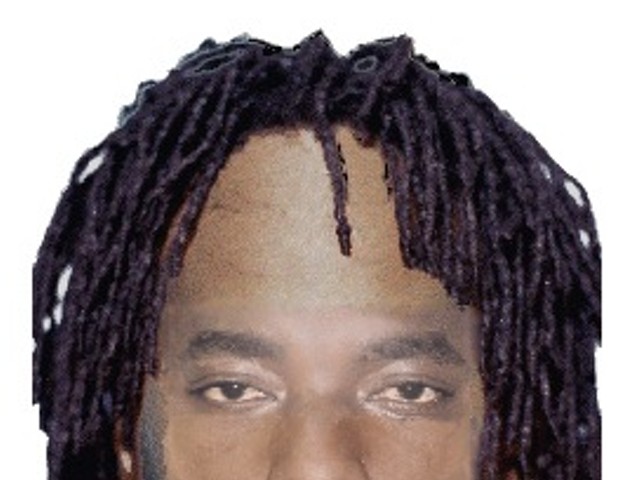

The boy was about six feet tall and slender, with collar-length twisties in his hair. He was hanging by a multicolored bed sheet, his sneakers just inches off the ground. The consensus among authorities was that it was a suicide. They cut down the body and carted it off to the morgue. The decision to order an autopsy is made by the coroner, but in this case, he saw no need to. Still, the deceased needed to be identified.

"We didn't know where to go," explains Cahokia Police Chief Rick Watson. For the rest of that day, he says, his officers interviewed residents and chased down leads to no avail. "We thought somebody would've reported their child missing. So here it is Monday morning, and we're still trying to find out who this kid is."

It wasn't until police reached out to their officer embedded in the school district that the search narrowed. Comparing yearbook pictures to police photos, officers hit on a match.

On Monday afternoon family members confirmed that the dead boy was fifteen-year-old Lester Wells Jr., an eighth-grader at Helen Huffman Elementary School. He lived less than a mile from the bridge.

Then, the rumors began to stir.

Some were uttered quietly after dark on driveways and front lawns, others brashly asserted in school lunchrooms or shot from cell phone to cell phone via text message. All of them contained the same premise: Lester Wells, a.k.a. "Stinky," never would've killed himself.

Some residents suggested he was strung up by a marauding band of Ku Klux Klan members, or that maybe the police strangled him and were trying to conceal it. Still others seemed convinced that Wells was killed in retaliation for the death of Blake Munie, a white teenager fatally shot by a black teen a few weeks earlier.

On Tuesday, April 27, Wells' mother, Crystal Teague, railed to the Belleville News-Democrat that police ruled her son's death a suicide without consulting her about his emotional state. He'd been excited to graduate and enter high school, she insisted.

Teague then told the paper that on the night her son disappeared neighbors claimed they saw the boy being yanked into a vehicle after an argument with the passengers.

The News-Democrat posted the story on their website. Within 24 hours readers' comments grew so vicious that the paper felt compelled to shut them down, a rare move for a story this fresh, says editor Jeffry Couch.

"With this one in particular, the racial comments started right away," Couch recounts. "And there were a bunch of rumors and attacks."

When RFT ran its own post on Wells' death, some commenters migrated there. "I'M HERE TO TELL U THIS," typed a self-described African American mother of two on April 30, under the name "Chris." "FUCKING CRACKERS, RACIST PIGS, BLUE EYE DEVILS KILL[ED] THAT BOY...WHAT WE NEED TO DO IS START KILLING THEIR FUCKING WHITE CHILDREN."

That same day, the Cahokia school district sent home a letter to parents that read in part: "As school leaders, we are very concerned about various conversations and rumors that have been circulating in the building and community regarding misinformation about the student's death."

Word quickly circulated of a second and then a third black youth found hanged to death. On the outer walls of Penniman Elementary School someone spray-painted a message urging violence to whites.

Chief Watson broke his silence on Tuesday, May 4, telling the media that no signs of foul play had been detected. He implored citizens not to make the tragedy worse.

His outreach efforts, though, failed to prevent that evening's village board meeting from spiraling into a tense exchange about what to do next. Several local ministers were present, reporting that the anxiety in their congregations had reached a fever pitch.

That week the FBI launched a formal evaluation of the police's casework. Reverend Johnny Scott of the NAACP's St. Clair County chapter came out in support of the police. Cahokia mayor Frank Bergman held his own press conference, promising transparency. The coroner, meanwhile, backtracked and decided to perform an autopsy and a toxicology report.

When the boy was finally buried on May 21 authorities still had not yet released their findings.

If in fact he killed himself, perhaps his reasons will remain a mystery. Yet one thing seems clear: Lester Wells Jr. may have been ready to leave Cahokia, but Cahokia, by all appearances, wasn't ready to let him go.

Cross the Poplar Street Bridge into Illinois, head south on Route 3 and swing past Sauget's raunchy nightclub strip. You won't find the famous Cahokia Mounds, which are eleven miles to the north in Collinsville. But you will find Lester Wells' hometown of Cahokia.

Today, the village of Cahokia is dwarfed by East St. Louis, but two centuries ago it was the seat of an enormous county that encompassed Illinois, Wisconsin, Michigan and half of Minnesota. In 1800, some 700 citizens lived here, many of them descendants of the first French settlers. By the end of World War II, it hadn't added many more.

Then the GIs returned home. Industry started booming during the 1950s and '60s in nearby Sauget and elsewhere, drawing folks from Arkansas and Missouri's bootheel. Subdivisions of affordable housing rose up, and by 1970 Cahokia's population peaked at more than 20,000. At the time, 99.5 percent of its residents were white, according to census records.

Mayor Bergman, who is white, remembers when school desegregation was enforced in the '70s and minority students were bussed in to town. "There were threats of violence, and schools were shut down," he recalls. "It was an explosive time."

Older whites started moving out, and younger African Americans started moving in. The numbers tell the story: In 1980, the U.S. Census counted 29 black residents in Cahokia. A couple decades later, there were nearly 6,300, more than a third of the village's population.

During that same period, the portion of residents living in poverty jumped from a tenth to a quarter. The tax base has shrunk, and Bergman says Cahokia, now with a population of nearly 16,500, is about $800,000 in debt.

"This town is hurtin'," says 57-year-old Jerry Nichols, zipping his golf cart through St. John's Garden, the subdivision where Lester Wells grew up. A portly white man with a close white beard, Nichols serves as committeeman of this neighborhood and the rest of Cahokia's 20th precinct. "It's never been this bad. Since they brought in the HUD and Section 8 housing, it's been miserable."

Several of the one-story homes on these streets, all bearing names of Catholic saints, are boarded up. Raw sewage seeps from a manhole where small children are playing nearby. Two sewers have caved in on St. Margaret road, leaving gaping holes in the pavement.

Nichols crosses Route 3 and parks his golf cart in front of his home on Garden Street. Many call this side of the highway "the white 'hood," even though some blacks live here.

Nichols is a retired steelworker. He welded together the huge cast-iron smoker that sits on his driveway. On this early May afternoon, with rain clouds approaching, he's grilling ribs. The smoke wafts into the road, and two different carloads of people stop and ask if he's selling barbecue. "Maybe I ought to!" he jokes.

Nichols says drug dealers are encroaching in the southern part of town and that the elderly people are "scared to death." He recently launched a petition drive called "Pull up your pants!" which would ban "unseemly exposure of undergarments," also known as "sagging." By the second week of May, he'd collected 171 signatures from folks of both races.

"I've only been refused by three people," he says. "Three black kids. The one young man asked me when they were going to pass an ordinance to prevent cross-burning."

Nichols remembers Lester Wells. Almost every day around 7 a.m., the retiree would look out and see the young man walking by. The boy would often sleep at his girlfriend's house then head home in the morning.

"He kept to himself, but he'd say hi," Nichols says, now sitting in his open garage. As he speaks, storm clouds outside are gliding in over the neighborhood, deep and dark as bruises. Wind whips up the tree branches.

Nichols believes Cahokia's racial discord has gotten worse from both sides. The groundless chitchat surrounding Lester Wells' death didn't help.

"The whole thing puzzled me," he says. "I hope they come out and say what happened to him. You got kids getting out of school soon. Things can happen."

From the moment Crystal Teague's eldest son, Travion, called her on April 26, she felt something was terribly wrong. "You know that sound and that tone," says the 34-year-old mother of five. Travion told her that his brother Lester was dead. She dropped the phone and raced up to Huffman Elementary.

A pair of detectives who'd been searching for her and other next of kin arrived at the school and found her there. She asked them how this could've happened. "They wouldn't tell me anything," she says. "They said I had to go to the morgue." Teague then drove over to the home of Lester's biological father, Armel Gines.

Gines, a.k.a. DJ Oatmeal, spins on WHHL (Hot 104.1 FM) and at nightclubs around town. He says he and Crystal had a "one-time thing" back in 1993 that resulted in Lester's birth. Crystal was eighteen. She decided to name the baby after the man she was with at the time, Lester Wells Sr.

It wasn't until the boy turned six, says Gines, that he learned that he was Lester's father. In the past few years, he would bump into Lester on the street and chat, but not often.

When Crystal pulled into Gines' driveway that late-April day she was already crying, fearing their son had died. "That blew my mind," Gines recalls. "Nothing like that had ever happened to me before." Hours later, he says, he received a text from her: The body found hanging from the bridge was indeed his son.

Two weeks later Crystal and her new husband, Omarr Teague, are sitting on the front porch of their home in St. John's Garden, where a makeshift memorial of stuffed animals, flowers and wooden crosses adorns her yard.

It is here where she held a crowded candlelight vigil in the days following the discovery of Lester's body. Soon after that, she says, she and Omarr packed up her kids and checked into a St. Louis hotel and stayed for more than week.

"We tried to keep their minds rotating," she says of her sons, Mallik, Chris and John-John Wells, all of whom live at the house (Travion lives with his father). Her own mind kept replaying the evidence photos of the hanging, the grim pictures detectives showed her to prove that a bed sheet could, in fact, support her son's weight.

Getting some distance from the house helped, but only a little. "Every time I close my eyes," she says, "I see my son."

Last year was a turbulent one on the home front. According to police records, officers were dispatched to the Teague household six times on domestic-disturbance calls, three made by the children. On one occasion, police arrived and Omarr reportedly smelled of alcohol and had a deep gash in his forearm. Another time he told officers that Crystal had threatened him with boiling water.

In January 2010, Crystal Teague experienced what Omarr described as a "nervous breakdown," which culminated in a suicide attempt. He had to bind her hands and feet to protect her from herself. When officers arrived, she wouldn't respond to their questions.

Omarr says they were married on February 1 of this year. Since then, no police incident reports have been filed.

Crystal says she nicknamed Lester Jr. "Stinky" because she had to constantly change his diapers when he was a baby. She remembers the young man as quiet and sweet, a patient listener who watched his brothers when asked.

Lester sometimes came to his mother with girl problems, but he never seemed deeply distraught or got into much trouble, she says. "He loved the music, and he loved the girls. That was his thing."

He did get into trouble once. In April 2009 he got behind the wheel of his mom's van and, along with some other kids, went joyriding. Teague found out, grew worried and called the police. When a patrol car caught up with the van, Lester floored it, initiating a high-speed chase through Cahokia that resulted in his arrest and two years' probation.

Outside of that, Crystal says, "He was not the type of child that made me sit up and worry about him." She did report him missing once last December, but he soon turned up. "He'd check in. He never went very far."

Lester often spent the night across Route 3 at the home of his girlfriend, Tamera Moore. Sitting on the front step of her trailer home, Moore says the two met in eighth grade at Huffman Elementary. The petite fourteen-year-old remembers how her boyfriend adored the rapper Gucci Mane and never seemed upset enough to want to hurt himself.

On the night he disappeared, both mother and girlfriend thought Lester was at the other's house.

Moore says it was painful returning to school soon after his death. "His desk was empty," she remembers, hugging her legs. "It was just too sad."

Cheryl Conner, Wells' teacher, saw how devastated his classmates were. On May 20 they released balloons as a tribute to him. "I loved this kid," Conner wrote in an e-mail. "He made me laugh. He was very respectful. He was in my heart, and I'll never forget him."

Back at the Teagues' house, Crystal says she's still adjusting. The other day she was hunting around for her phone and called out to Stinky, asking where he'd put it. "Sometimes I catch myself," she says. She looks toward the stuffed animals on her front lawn.

On May 4, nine days after Lester's body was discovered, a large and anxious crowd converged for the semimonthly village board meeting at the Cahokia Nutrition Center for Older Adults. Police officers with metal-detector wands screened all citizens filing in. Once the Pledge of Allegiance was said, the proceedings swiftly degenerated into sniping between the six-member board of trustees and Mayor Bergman.

A loose coalition of mostly African American trustees, led by Kyle Johnson and Trevon Tompkin, accused the mayor (among other things) of misusing funds and running the town as a "dictatorship." At one point the normally quiet village clerk, Bernadette Wiggins, lost her cool with Bergman, called him a liar and shouted, "Excuse me, mayor, I respect you as a mayor, but I don't respect you as an honorable man!"

For his part, Bergman — a thick-set strawberry-blond who speaks in a croaky drawl — denied the accusations. With the end of his second four-year term approaching next spring, he has yet to announce whether he'll run again, but that evening he put up a fight.

Trustees Johnson and Tompkin are currently fighting criminal charges of voter fraud from the April 2009 municipal elections, a fact to which Bergman alluded several times.

On it went for the first 45 acrimonious minutes, with all parties talking over each other on hot-button issues such as the sewers and the hiring of police officers. Each side even had its own attorney present.

Then the conversation turned to the hanging death of Lester Wells Jr.

A black man said he'd heard that any children of his race caught walking outside after 7 p.m. would be snatched up and hanged. "I'm scared for my kids, man," he said. "Am I supposed to walk around with my pistol on my side and fear for my kids' life?" Mayor Bergman replied that he did not recommend that.

Later the same man asked, "Can you treat the severity of the case for our kids the same way you would with yours?" Bergman said he would — after all, many of his own family members are black or biracial. But, added the mayor, because the FBI had intervened, his access to information was restricted and his hands were tied.

At this, an African American woman rose to leave in protest. "He's unconcerned, nonchalant," she snapped. "If it was his child, he wouldn't want his child hung. No, don't tell me to calm down for hanging somebody! Don't tell me to calm down!"

Bishop Henry Phillips from Power of Change Christian Center then spoke. "I'm a little disappointed we in the community have not heard from you," he told Bergman. "This thing is unraveling.... We need you to lead us."

Pastor Barry Simmons of New Visions World Ministries echoed the sentiment. "I'm gonna be honest with you: If that were my son, I'd want to hear from you.... I need you to go to that house, I need you to get the chief, yourself — and if you need any one of these pastors, we'll go. And you need to make it right with this community, because we can't have this. This is not right."

Simmons decried all the bickering. "It's becoming a war — I had no idea. This is not the way a community is to be ran, and I will not stand here as an educator in this community and let you or anyone bring it down."

Bergman said he'd been sick over the weekend and was unaware how widespread the fear had become. He also wondered aloud why the pastors didn't bother calling him when they heard talk of a lynching.

"I am here as your friend, Frank. We know each other," Simmons responded. "Don't bite us. Reach out and grab us. Let's handle it as men and women of honor and dignity."

Three days later, on May 7, Bergman stood before reporters from three TV news crews and two newspapers — his biggest press conference ever, he later noted. Flanked by Simmons, Pastor James Heard of the New Psalmist Church of God In Christ, and a representative of Phillips' congregation, the mayor announced that the FBI had assumed jurisdiction over the Wells investigation.

Offering his condolences to the Teague family, Bergman said authorities believed it to be a suicide. But whatever their conclusion, he assured those gathered that the truth would eventually prevail.

When Simmons took the podium, a reporter asked if he'd ever heard so many rumors about a death. "I've been in Cahokia 22 years," he replied, "and I've never been involved in any situation of this magnitude."

As the news crews packed up their cameras, another reporter asked the pastors what Lester Wells' death revealed about Cahokia.

Simmons bristled. "It's not that we're finding out what we are," he said. "Any community would react the same way. You just saw a community come together in love."

The reporter replied that he just wanted to learn as much about Cahokia as possible.

Simmons informed him: "You might never know how we tick."

Two weeks after her son's death, Crystal Teague confirmed that the bed sheet used in the hanging came from her house. Her dogs used to sleep on it. Police reports state several times that the body showed no bruises, scratches or any signs of struggle. The boy's clothes were not dirty or torn. Detectives also noted no drag marks or footprints in the area to suggest that other subjects had been present.

Still, Teague remains convinced her boy was murdered. When she asked for an autopsy, she says, authorities gave her the runaround, and that made her suspicious.

Dr. Morton Silverman, of the Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience department at the University of Chicago, says many parents go into denial after a suicide. "To accept the fact that it was a suicide means that they have to give long and hard thought to what they might've done differently or if they could've done anything at all. And that process is wrenching for people to go through. If you say, 'Well, it wasn't a suicide,' then you don't have to do that."

He notes that parents often get blamed even though it's not their fault. Some suicidal kids don't show any symptoms, he says. And even when they do, moms and dads don't necessarily know what to look for.

Silverman concedes that Lester Wells' death was not a typical scenario. However, he points out, suicide is third leading cause of death for black males fifteen to nineteen years old, and hanging is a common method for adolescents who don't have access to a gun.

Silverman is not surprised by all the back-fence gossip swirling around Lester Wells' death. "People always try to find rationales for anything that happens, whether it makes sense or not. But sadly, a high number of adolescent suicides are not explainable to the extent we could sit down and say the reasons are X, Y and Z. We don't always have information. We don't always know what triggered the final decision."

Of the more than 50 readers who commented online after RFT's initial post concerning Lester Wells, only one signed her real, full name: LaJuan Berry, a sixteen-year-old honors student at Cahokia High School.

"Kill all the whites REALLY?!?!" she wrote on Sunday, May 2. "That is some crap. Because some of my CLOSEST friends are CAUCASIAN!! And I'll be damned if they come up dead."

She felt compelled to post again several minutes later. "How would Dr. King feel if he was here to witness this extreme ignorance?? Or what about Rosa Parks, all these PROUD AFRICAN AMERICAN PEOPLE fought so we could be treated equally and yall dumb asses ACT like yall wanna be treated like niggers...HAVE SOME SELF RESPECT!!!"

Last month she was called into her principal's office for an interview. She arrived clutching a copy of Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird, which she'd been reading in her English class.

The very fact she felt obligated to weigh in as the voice of reason makes her angry, she explains. "That shouldn't be coming from a child; that should be coming from an adult," she says. "I think the adults are putting gas on the fire."

At school, some of her fellow students have linked Lester Wells to nineteen-year-old Blake Munie. On April 7, Munie was shot at close range while sitting inside his vehicle. He managed to drive two blocks before crashing into a utility pole in front of his parents' house.

Two days later, Craig Nichols, a black teen, was arrested for the crime. The buzz around town was that Wells was randomly targeted by whites looking to avenge Munie's death.

The Munies, like the Teagues, held a candlelight vigil for their son and erected memorials in their front yards, complete with white crosses.

LaJuan Berry says racial tensions have grown more visible in Cahokia. She remembers, for example, going to Wal-Mart recently and holding the door for a white couple followed by a black couple.

"The black couple said, 'This ain't the '60s; you ain't got to hold the door open for them. They can hold the door open for themselves.' And I was like, 'It's just common courtesy. It's just something you do out of respect for people.'"

On May 21, Lester Wells Jr. was given an open-casket funeral at Mount Zion Missionary Baptist Church in East St. Louis. He lay in a white suit and striped tie, surrounded by bouquets of soft blue flowers.

The church was crowded with well-wishers and family, many wearing shirts that bore Wells' photo and the letters RIP.

When Crystal Moore first approached the casket, she let out a series of loud, sudden gasps. Family members pooled around her as she sobbed, fanning her neck.

The broad-shouldered Omarr Teague was the first one of them to take the podium and speak. Sporting cornrows and a short-sleeved polo, he talked fondly of Lester, remembering how he helped him write some rap lyrics. He wants to be a role model for his stepsons.

"Even though I'm not their biological father, I still love them like they're mine," he said to applause, fighting to steady his voice. "I can't even go into his room anymore. That was my guy. No matter what nobody heard, that was my little man."

Toward the end of the service, Bishop Henry Phillips told mourners, "Cahokia needs to come together. Out of this tragedy has brought unity among the churches. This is not the time to point fingers. I want to say this to all of you that live in the community: Cahokia is going to make it."

Last week chief deputy Danny Haskenhoff of the St. Clair County Coroner's office informed RFT that the toxicology tests run on Lester Wells Jr. came back negative for the presence of drugs or alcohol.

The autopsy report, Haskenhoff said, showed Wells "died from hanging himself."