There were some very bad vibes in downtown St. Louis on the night of October 28, 2013. The Cardinals had just lost Game 5 in the World Series, and the Rams had a pathetic showing against the Seahawks at Edward Jones Stadium. The streets were jammed bumper to bumper with disgruntled fans trying to make it home, and so Brandon Pavelich and Julia Fischer — two college friends on a kinda-sorta first date — decided to walk around a bit before attempting to leave the area.

Then they heard fast footsteps, and the next thing they knew, two men had guns pointed at their heads. They demanded money and cell phones.

Pavelich paused.

"Show him we're serious and shoot him," he remembers one of the men saying.

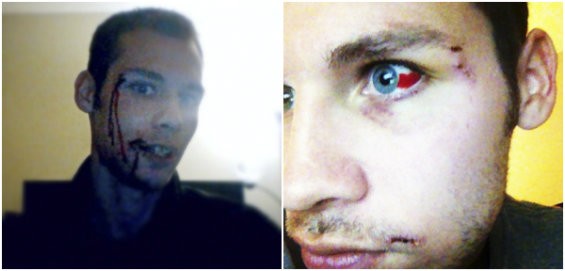

Instead, a gun smashed into Pavelich's face, opening a gash in his forehead and chin, and chipping a tooth. One of the men reached into Pavelich's pockets as he was reeling, and grabbed his iPhone and cash. They took Fischer's iPhone as well, and ran.

Luckily, Pavelich and Fischer found a St. Louis police officer nearby. They soon learned theirs was the last in a string of muggings that evening. In total, seven victims had their phones taken, though Pavelich was the only one who had to spend the night in a hospital getting stitches.

Fischer recalls that the police behaved as if they were hot on the trail of the stolen phones.

"They did say that they're tracking it," she says. She assumed that meant they were using the phones' GPS or something like the Find My iPhone app.

By the next day, four suspects were in custody, including a supposed lookout and a getaway driver. They were found in a hotel room in Caseyville, Illinois, allegedly with the stolen phones. Among the recovered property, Pavelich was able to identify the case he'd had on his phone. It seemed like a done deal.

But a year and a half later, as the trial date for three of the men got closer, Fischer called the prosecutor to find out when she needed to be in court. That's when he told her they'd dropped the charges.

"The reasoning was, there came up some legal issues that would cause insurmountable issues so that they wouldn't be able to continue with the case," says Fischer. "That's really all that they told me."

Two weeks later a story in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch helped shed some light on what happened. Titled "Controversial secret phone tracker figured in dropped St. Louis case," it explained that investigators had used a relatively new tracking device called a cell site simulator to trace one of the stolen phones. It was so accurate — more accurate than GPS — that it was able to pinpoint the exact hotel room where the accused thieves were holed up.

The technology is often referred to by a brand name: StingRay. When deployed, StingRay forces any cell phones in the area to send it a signal, the same way that a phone normally sends a signal to cell towers. Even if a cell phone is not in use, it still transmits its phone number and electronic serial number to the device.

Once a tool used by federal officials for combating terrorism, in the last decade StingRay-type devices have been approved for use by local law-enforcement agencies. Officers have been using the technology under the purview of the FBI — and only under strict orders not to disclose anything about it, even in court.

The Post-Dispatch story about Pavelich and Fischer's case hypothesized that authorities were backing away from the charges because they did not want to be forced to put a police intelligence officer on the stand and reveal how StingRay works — that government secrecy was essentially more important than a conviction. That did not sit well with Pavelich.

"I got hurt by these guys pretty bad, and they're just walking free now. It pissed me off a little bit," he says.

It may not be quite as simple as that. The St. Louis Circuit Attorney's Office has insisted repeatedly that the use of a StingRay is not why they dropped the case against the four suspected robbers.

"Contrary to the opinion of defense attorneys and to recent reports in the media, the dismissal of the cases was not related in any way to any technology used in the investigation," Lauren Trager, a public information officer for the circuit attorney, said in a statement. She declined to answer further questions about the case, as it is now considered a closed record.

Regardless of why the case was thrown out, it shows that one thing long suspected by local activists is now certain: St. Louis police are using StingRay devices or ones with similar data-capturing capabilities in their investigations.

Until recently, First Amendment watchdog groups like the ACLU said only that it was "probable" that StingRays were being used in St. Louis. But this case, along with documents obtained by Riverfront Times, are beginning to shed some light on the practice locally.

And now that StingRay is here, privacy advocates have a host of concerns: that innocent people's data may be collected without their knowledge, that merely deploying the device is equivalent to unconstitutional search and seizure, and that it may be used to spy on those simply exercising their legal right to free speech.

Local attorneys, journalists and citizens have joined those in other American cities (at least 51 state and local jurisdictions by the ACLU's count) who are struggling to understand StingRay, and are finding a wall of law-enforcement silence on the other side of their questions.

"It's ridiculous," says Hanni Fakhoury, senior staff attorney for the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a civil-liberties advocacy nonprofit. "It's secrecy for the sake of secrecy. It's not actually a public-safety issue now."

[View as a single page.]