DANNY WICENTOWSKI

Gwendolyn Cogshell holds a sign urging school officials to "Invest in our children" during a teacher's union press conference opposing school closings on December 15.

The largest mass closing of St. Louis city public schools in more than a decade has arrived — and although public outcry in December led the St. Louis Public School Board to reduce its initial target from eleven to eight schools, the board members who reconvened to vote on January 12 did so under a cloud of a familiar disappointment.

The school board meeting closed on a vote to shut down four elementary schools: Clay, Dunbar, Farragut and Ford. The district will also close Fanning Middle School, Cleveland Naval Jr. ROTC and Northwest high schools. Carnahan will be converted into a middle school.

The closures are controversial, though not as sweeping as the eleven-school proposal, revealed in December, that sparked immediate backlash: Parents showed up to protest at the district office, while hundreds left statements at a public hearing to plead for solutions that would keep the institutions open. The chorus was joined by the St. Louis Board of Aldermen, which passed a unanimous (though non-binding) resolution opposing the plan to upend more than 2,000 district students and 200 staff.

But now, one month later, the sound and fury appear to have signified almost nothing.

Indeed, after the school board announced a "pause" in response to the backlash, board members said they hoped the extra time would bring new resources and political energy to the city's longstanding education crisis: While St. Louis' school system was built for a 1960s-era enrollment of more than 100,000 students, it now musters an enrollment of fewer than 20,000 students spread over 68 buildings. Some schools are unable to fill even half their classrooms.

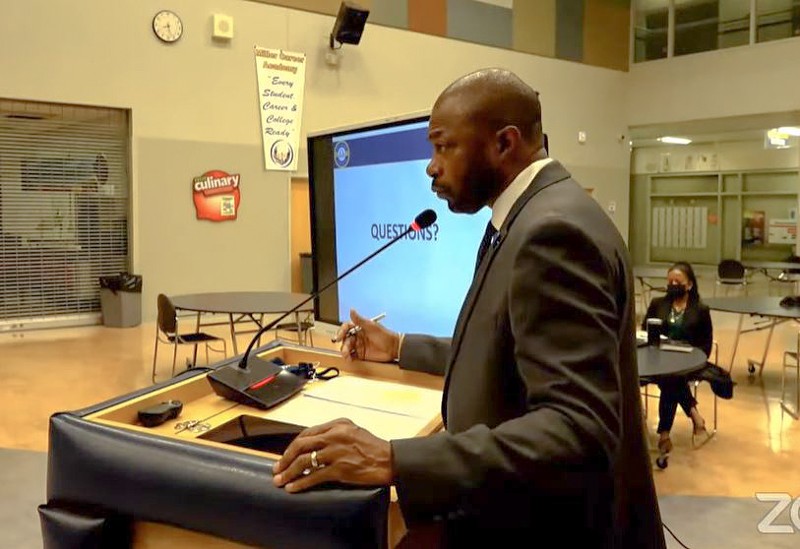

Simply put, St. Louis has too many schools, too few students, and the imbalance is draining resources from the district. A month’s delay hasn’t changed that. During the January 12 school board meeting, Superintendent Kelvin Adams revealed that he'd spent the extra time meeting with representatives of nonprofits, alumni organizations and elected officials who argue St. Louis still needs its school buildings because the population is on the rebound. It is a perspective he does not share.

"I am not believing that we're going to get 10,000 kids coming here next week," Adams told the board, adding that other ideas raised as alternatives to closures would "require a great deal of time."

That’s a resource St. Louis’ teachers and students don’t have, Adams said. Tangible help from city leaders is also in short supply: Despite the high-volume opposition to the closings, Adams and other board members lamented the lack of interest by elected leaders during the delay. Among the four candidates currently campaigning for St. Louis mayor, only one, Cara Spencer, sat down with the school board to discuss the closures.

Still, Adams said the delay had given him time to reevaluate two elementary schools included in his original proposal, Hickey and Monroe, which he said show potential for growth among preschool students and should not be closed. Adams also said various groups, including Harris-Stowe State University, have pledged support to save the historic Sumner High School, which traces its roots to 1875 as the first African American high school founded west of the Mississippi River.

Similar support was not available for the other schools marked for closure. During last week's school board meeting, Adams presented the board with four options, including his original proposal. One option, “Option 3,” would close just four schools on the condition that the city’s Board of Aldermen pass a moratorium on any new schools (including charter schools) until there is a “city-wide plan for schools” under the city’s next mayor.

To make this option work, Adams continued, the city-wide plan would have to be in development by October, and it would have to include reforms to the city’s controversial use of tax incentives to fund private developments, as those incentives drain revenue that would otherwise go to the school district.

It was this set of requirements which raised the most debate during the meeting. On one hand, Option 3 would be a relief to alumni and parents of students at six elementary schools. But it also meant trusting St. Louis’ political leaders to accomplish city-wide policy goals.

For some of the school board members, this was apparently too much to ask. Several critiqued the empty promises of the city's powerbrokers and the overwhelming silence that followed last month’s splashy statements, tweets, and non-binding resolutions.

“I will not support Option 3 with the idea that our elected officials are going to, all of a sudden, come up with a plan,” board member Regina Fowler said. She noted that the Board of Aldermen would have no “meat” in a non-binding moratorium that could actually prevent new schools from opening in St. Louis, and that tax incentive reform “is a long-term solution, which I agree with, but it doesn’t affect the decision we make today.”

Similarly, board member Susan Jones said she was dismayed at the lack of attention to the school crisis on the part of elected officials, particularly in an election season. “My fear,” she explained, “is that we'll choose an option with the idea that they [city officials] are going to do something.”

On the other side of that fear is St. Louis’ dwindling population and what happens when both SLPS and charter schools court the remaining school-aged children. Board members agreed that the city should pursue a moratorium on charter schools, which are publicly funded but run independently from school districts.

But while he supports a moratorium, Adams acknowledged that such a restriction would require action by the state’s conservative-dominated legislature, which has spent years trying to pass laws to expand charter schools in Missouri. Indeed, a bill currently pending in the Missouri Senate, sponsored by Republican St. Charles lawmaker Bill Eigel, would make it illegal for St. Louis to refuse to lease or sell city property — including closed SLPS buildings — to charter schools.

In his remarks to the board last week, Adams urged the members to consider the stakes of their vote. He reminded them that 62 schools had closed in St. Louis since 2003, including fifteen charter schools, and the city was still “saturated” with education options. If the board didn’t act, he warned, they wouldn’t have to wait another decade before taking up school closures again: They’d be “back at this table” every two years.

In the meantime, Adams concluded, “this community and the resources are being squandered away, and I don’t think they need to be squandered to support the students we have.”

After more than two hours of debate, the board voted 4-3 to close eight schools and to delay the final decision to close Sumner until March. The narrow vote reflected the anguish around closing a school, which Adams previously said can feel "like a death" for students and the surrounding neighborhood as they are forced to watch the formerly beloved building degrade into vacancy.

But the vote signaled something else, too: St. Louis’ education system won’t keep waiting for someone to save it, and its elected school board has run out of confidence in city leaders.

In the end, that means eight schools have just run out of time.

Follow Danny Wicentowski on Twitter at @D_Towski. E-mail the author at [email protected]