What happened next — how much he stole, whether he truly pistol-whipped someone, whether he got caught — depends on which staffer you ask. Eat-Rite lore is like that. Details get added or elided over time. But it's a decent yarn, and a decent yarn can pull you through the night shift.

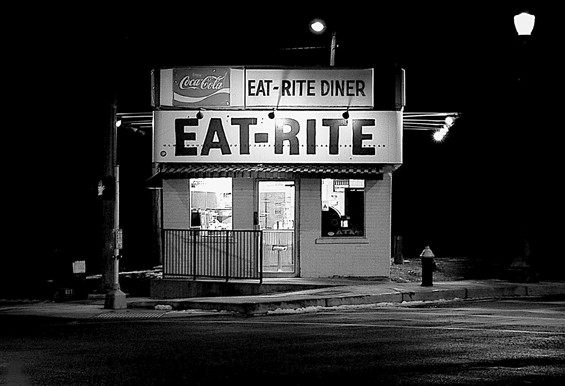

Last week, Riverfront Times sat through three consecutive night shifts at the Eat-Rite Diner at Chouteau Avenue and Seventh Street. It's fair to wonder why. The menu hasn't changed much in 45 years. The building is just a 516-square-foot dive a few blocks south of Busch Stadium. Only thirteen customers can eat at the counter at a time. It grosses maybe a few hundred bucks on an average night.

Yet Eat-Rite is unique in our city's nocturnal ecosystem. It's the sole kitchen within a three-mile radius of the Arch that stays open all night and lets you dine in — making it a sort of bottleneck, a place through which the peckish must pass to get their after-hours pancakes or omelets.

- See also: St. Louis' Most Hangover-Friendly Diners

It attracts St. Louisans of all moods: the drunks and demons, clowns and curmudgeons, philosophers and philanthropists. At Eat-Rite, you chow down next to folks who didn't attend your high school and don't care about your career. Black, white, 99 percent or 1 percent — sometimes the only trait you share is a craving for the slinger, that hot wreckage of breakfast foods that the owners, the Powers family, claim they developed three decades ago.

In that sense, Eat-Rite is nothing like Nighthawks, Hopper's romantic rendering of a late-night diner. It's not a spare, glassed-in cavern in which you brood at arms length from your neighbor. It's a bunker, your neighbor's arm is draped around your neck, and he's eating your fries.

The daytime crowds are tamer. Cops and postal workers order carryout. Local celebrities Chuck Berry, Jack Buck, Jim White, Francis G. Slay, Claire McCaskill, Mike Shannon and David Freese have all hunkered down at the Formica counter.

But if you endure three overnight shifts, like we did, you'll watch a whole city cycle through. You'll see St. Louisans on their worst behavior, and their best. You'll see the ways in which Eat-Rite's staff are models of civic patience, and you'll witness the acts of kindness they perform on the sly.

We could use more citizens like them.

St. Louis has had a rough year. Just like the Eat-Rite bandit's warning shot in the '80s, the policeman's shot that killed Michael Brown in Ferguson last August seized everyone's attention. The fallout reminded us that residents here don't enjoy protection, power and money in equal measure — and that we don't agree on who's to blame for that, let alone how to fix it.

Eat-Rite itself had a rough 2014. Twice its exterior was smacked by vehicles. The first time was so bad the owners had to shutter for a month to replace a wall. Inside the eatery, the atmosphere tightened as unrest gripped the city.

But the staff kept pouring cups of coffee. Regulars kept coming back to sip them. Everyone soldiered on.

The diner, we predict, is going to make it. Just like the city that surrounds it.

City records are vague, but the brick walls of 622 Chouteau Avenue were likely laid in the 1930s. The nearby Maronite church of St. Raymond's was a hub for Lebanese immigrants back then, and two of them, Elias and Elizabeth Mahanna, began grilling burgers at the shack in 1935. They called it White Kitchen.

As a concept, the diner soon took off across America. With the postwar economy churning, blue-collar families found themselves with extra cash to splurge on eating out.

In St. Louis, L.B. Powers' family rode that wave. His uncle ran the Courtesy Diner at Olive and 18th streets. Employed there at age sixteen, L.B. fell in love with a customer — a receptionist named Dorcas, whom he quickly married. (Years later, Universal Pictures would film a romance in that same eatery — although White Palace, starring James Spader and Susan Sarandon, was based on a novel, not their courtship.)

Before long, the couple had five kids and had amassed six diners dotting south city and county. They started calling the chain Eat-Rite after 1963.

By that time, America's middle class was fleeing the city for the suburbs, so diners followed them. Restaurateurs labored to gussy up their eateries by adding booths and waitresses, by hiding their kitchens, and by cordoning off sections for teens, as Andrew Hurley reported in his cultural history Diners, Bowling Alleys, and Trailer Parks.

But the shack at 622 Chouteau stayed old-school: just a kitchen, counter and stools. Bucking the suburban trend, the Powers bought it in 1970. Dorcas cringed at the slummy locale.

"It was a terrible disgrace," she recalls. "People were squatting in these shacks with no electricity or water."

Yet the couple stuck it out, and their gamble paid off in the 1980s, when Ralston-Purina started cleaning up the area. The Powerses eventually sold off their other Eat-Rites to employees and friends, but they held onto 622 Chouteau.

To this day, the decor inside is quaint yet unsentimental. There's a cigarette machine, plus a Can-Can pinball game from 1961. But no memorabilia adorns the walls. Just a "NO SMOKING" sign, a pocket Cardinals schedule, and two hand-written notices: "CASH ONLY" and the unfortunately worded, "We cannot service you while on your cell phone."

Next: The men who work the night shift