Grieving the Cat I Never Wanted

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "41932919",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100

}

]

My cat died last weekend.

After more than two years of trying to support her failing kidneys, my wife and I realized it was time to have her put to sleep. It sucked, even more than I expected it to suck. I mean, I am a 37-year-old non-crier, and I started crying before we could even get out of the parking lot of the veterinarian’s office.

If you have ever spent much time at the vet, you have probably seen some stricken person walking out with an empty pet carrier. That was us on Saturday.

Lucy was not even really my cat. My wife picked her up fourteen years ago from a co-worker’s son in Colorado. Together, she and Lucy moved to Florida and then New York City, where I eventually joined them. I was not a cat person, but Lucy was part of the deal.

We decided in 2015 to move back to the Midwest, where my wife and I had grown up. We packed everything we could in the car and wedged Lucy’s carrier between our seats for the two-day drive from Brooklyn. When she howled, we decided to let her out so she could roam around a little. I remember the looks I got from a carload of dudes who pulled alongside us while Lucy sat on my lap.

My years with Lucy played out like a terrible romantic comedy: two badly matched characters thrown together by circumstance, destined to overcome their differences. My wife would tease me whenever she spotted Lucy curled up on my lap as I rubbed the back of her neck.

“That cat loooves you!”

“No,” I’d say. “We are enemies.”

Maybe all of this sounds like a little much, and I would agree with you. I’m not sure why I feel like writing an obituary for a cat. Except that, over the past two years, I have seen those other people hauling away those painfully light pet carriers, and those little tragedies haunted me.

I remember an older lady who sat next to us in the vet's lobby one day almost begging to be told her cat would die naturally in its sleep without pain or need for euthanasia, even as a hapless vet tech patiently explained the reality: Her pet would wither and suffer, essentially starving until it finally died.

During an interlude, the woman told my wife and I that two of her relatives had recently died and she could not bring herself to tell someone to kill her cat. “I just can’t do it,” she said.

I don’t know what she ultimately decided, but I do know that making that call is excruciating. You wish for a heart attack or a stroke or, at the very least, something definitive to let you know it is time. But the truth is that it's a judgment call. We did not want Lucy to suffer, but it is not like she could tell us how she felt. How do you know when it's time?

Two years ago, over a long Fourth of July weekend, Lucy quit eating, and we took her first to our vet, and then an emergency clinic because nowhere else was open after hours. We were told her kidneys were shutting down and she might have just weeks left. A young, red-haired vet told us he could put her down, or they could keep her there and try to stabilize her levels with medicines and fluids for a few days. The latter was the more expensive option, but that’s what we chose.

We drove around for hours during the following days to avoid the empty apartment and all its reminders of our gravely ill kitty, who might not return. Knowing how upset we were, the vets would call us in the middle of the night and tell us we could swing by and visit Lucy for a few minutes while everyone was away. We would jump in the car and go. It felt crazy in a way, to be so attached to a cat, but we just went.

Finally, after $1,800, Lucy came home with no guarantees. I remember thinking I had spent less on used cars, but we did not regret it. Lucy recovered with the help of a new regimen of powders and pills that we mixed into her food twice a day.

It really was amazing. She began doing things she had not done in months, sprinting back and forth across the living room in the middle of the night, the sound of her claws on the hardwood rattling us awake. We had to loop the cords for window blinds out of her reach to prevent her from batting them in endless battles. If we ordered pizza, we had to weigh down the box with a heavy pot lid because the smell of pizza made her crazy and she could once again leap onto the kitchen counter for a bite.

I think I came to like Lucy so much, because she was so completely herself. She controlled all of her relationships. If she wanted to be petted, she came to you — not the other way around. My wife and I began talking about "pets" as if they were units of measure for each stroke of a cat's fur. When it was time to pay up, Lucy would arrive like a tiny bill collector, find the closest available hand and headbutt it until we delivered the owed balance of pets, preferably behind her ears, under her chin or atop her back hips.

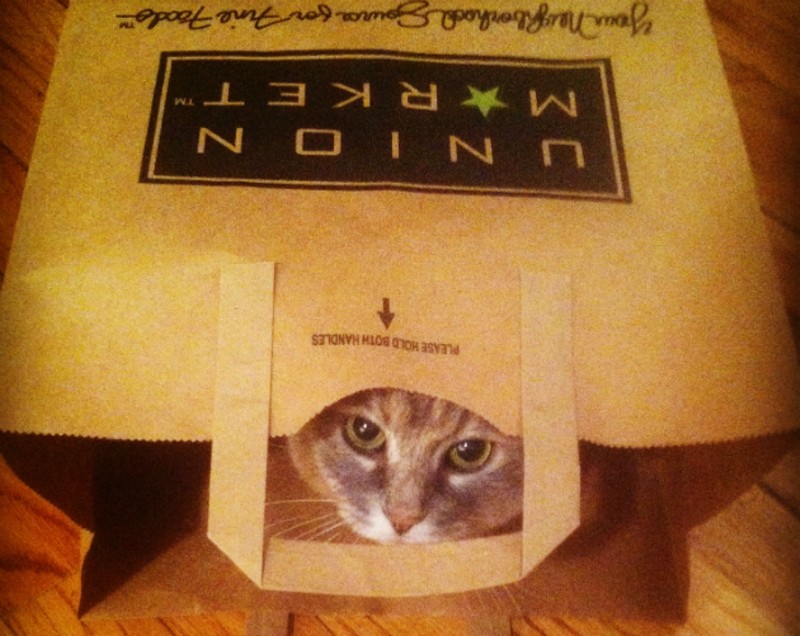

If you managed to hit just the right spot on those back haunches, she would tilt her head up and rapidly flick out her tongue as if lapping milk out of the air, which was hilarious. She had so many funny little quirks like that. When I would come home from grocery shopping, I would drop one of the empty paper bags on the floor, because Lucy would nose her way in, turn around a time or two to check the place out and then sit, peering out at us from her new home.

Some nights, we would be sitting on the couch, watching TV, when Lucy would sprint across the room, attack her scratch post like a lion ambushing a gazelle and then sprint away after a few seconds of furious pawing. On others, she would slip so quietly and naturally onto my lap that I would look down and wonder how long she had been there.

In March, my wife and I had a son. We were instantly obsessed — I assume this will continue, basically, forever — and life around our home shifted. Instead of sitting for hours with Lucy on our laps, we hovered around the baby or scrambled to do any of a thousand new baby-related tasks. We are tired people now, and Lucy had no mercy. When we would manage to lull our little boy to sleep, Lucy would bolt into the doorway of his bedroom, yowling for the attention unjustly denied her.

There are few things more terrorizing and infuriating to new parents than the sound of a cat screaming after you’ve put the baby to bed. You can almost feel the expectation of a few free hours disappearing as if someone is physically ripping them from your body. More than a few times, I would scoop Lucy up in my arms and hurry away down the hall, hiss-whispering curses in her ear.

These are the moments that made me feel guilty when Lucy’s health began to collapse again. A couple of weeks ago, her appetite began to flag and she had vomited multiple times. My wife took her to the vet, who told us her kidney function had taken a sharp dip, as opposed to the long, steady decline of the past couple of years.

One of the few options we were told we could try was giving her extra fluids through subcutaneous injections. Two years ago, vets at the emergency clinic had floated this as a possibility. But I never saw that as feasible. Lucy hated any sort of forced treatment so much that, when she was stronger, vets had to wear leather falconry gloves to handle her, as if protecting themselves from the talons of a great flying predator. The idea of us chasing her around with a needle and an IV bag of liquid seemed about as plausible as asking me to perform minor surgery.

On this recent visit, our vet juiced her up with the fluids and sent her home for us to monitor. Lucy seemed to feel a little better, but unlike previous rounds of fluids, the effects did not last long. We struggled to get her to eat, watching hopefully on good days and growing more concerned on bad ones when she left her bowl mostly full. She began to hide under our bed or paw open the coat closet and slip into the dark. On Thursday and Friday, she threw up multiple times, and my wife again called the vet to see what we could do.

Lucy usually slept on the bed next to us, but she slept on Friday night in the coat closet. We were told we could bring her in at 8:30 a.m. on Saturday, a half hour before they normally opened. Ostensibly, this was another status check, but we knew it was probably the end.

They took her in the back and sedated her for an exam. A few minutes later, the vet came out and delivered the bad news. Lucy had lost about a pound since her last visit and was getting worse. The doctor told us if we weren’t going to do the subcutaneous fluids, “it’s probably time.” We gave the OK, and they brought our cat to us in the exam room. She was pretty out of it. I could see her tongue poking out of her mouth a little. My wife and I petted her as the vet injected two syringes — first a pink liquid and then a clear one — into a port attached to her leg. She checked Lucy’s heart and then told us, “She’s gone.” The vet and her assistants left us alone with her and told us to stay as long as we liked.

It was quick and a little hard to believe. Looking down at Lucy, it felt as if we could call them back. “We’ve changed our minds,” I imagined telling them. But of course, it was too late for that. After a few minutes, we picked up our empty carrier and walked out through the lobby. It was full of people by then, and I am sure they had heard my wife crying in the room or could, at least, read our faces as we walked outside.

My in-laws had stayed with our son while we were off with our cat. They hung out while we cleared away Lucy’s things. My wife gathered up the litter box and bowls for food and water. My father-in-law helped me move an old couch into the basement, and we rearranged a few things to replace the empty spaces.

It has now been a couple of days, and it still sucks. I can hear the vet saying that bit about if we weren’t going to do the fluids, and the “if” feels a little like a dig, like maybe we should have done more. I don’t think she really meant it that way, but that’s how your mind works when you have to make those kinds of decisions. I remember the older lady telling us “I just can’t do it,” and I think of how miserable Lucy would have been if we had tried to hold her down and stick a needle in her a few times a week. Maybe I’m rationalizing, but I honestly think doing any more would have been solely for our own benefit and prolonged Lucy’s suffering.

A bunch of my wife’s friends and relatives have sent her messages of condolence. They are kind and suggest distracting herself with the baby, which is well-meaning advice and does help somewhat. But strands of Lucy’s hair are still on everything, and our son had just started to notice the small, furry presence prowling around our rooms. “I wanted a baby and my cat,” my wife says.

For me, I remind myself repeatedly that this was a cat, not one of our human relatives. But I find myself glancing at shadows at the corners of my vision. You develop a subconscious vigilance when living with pets. Lucy was liable to dart out of the dark and right into the path of your foot if you were not paying attention. I had been keeping an eye out for her all these years.

Now, walking around our quiet house, I swivel my head only to be reminded she will never be there again. I’m only seeing shadows.

We welcome tips and feedback. Email the author at [email protected] or follow on Twitter at @DoyleMurphy.