The music world is abuzz with Wu-Tang Clan's announcement last week that the single copy of the group's double-album, Once Upon a Time in Shaolin, will be sold, like a Rembrandt or a Rothko, at auction sometime this year.

It's a lavish production. The album comes "presented in a hand carved nickel-silver box designed by the British Moroccan artist Yahya," the group's website says. Inside the box is another intricately carved case, within which will be the actual disc. The music will feature guest performances from Cher, Redman, Carice Van Houten and more, including FC Barcelona soccer players, whatever that means. (You can hear part of Cher's contribution over at Forbes; the 51-second snippet is the only part of the album that has been released.)

The winning bidder will get to do whatever with the 31-track album -- lend it to a museum, place it in a personal collection, release it online for free, melt it for scrap, whatever -- and if RZA was telling the truth when he said the group had received a $5 million offer for it, then the album will probably fetch a similar amount, possibly more, at auction.

It might be the most brilliant way to release an album ever conceived in the digital age.

Wu-Tang Clan, of course, is legendary. The group's collective albums and solo projects are among the most acclaimed in all of hip-hop, and when the group does something, the rap world listens.

And there's no doubt: Once Upon a Time in Shaolin is a statement. It is a bold counterstrike against the streaming music economy, a move that maximizes scarcity in a world where the Internet has made music as ubiquitous as air.

"By adopting an approach to music that traces its lineage back through the Enlightenment, the Baroque and the Renaissance, we hope to reawaken age old perceptions of music as truly monumental art. In doing so, we hope to inspire and intensify urgent debates about the future of music, both economically and in how our generation experiences it," reads the Clan's statement of purpose for the album.

Just look at how the group broke news of the album last year -- through Forbes, not exactly a pop culture tastemaker, but rather the magazine that catalogs those with ungodly sums of money. This is a business move, a page taken from the lucrative fine art world, as much as it is an artistic one.

When Taylor Swift wrote in the Wall Street Journal that "music is art, and art is important and rare," she got most of it right. Music is indeed art, and art is important, but does that mean art is rare? Does a work have to be scarce to be considered art? In the visual art world, where original paintings can sell for eight figures, sure. Music has never worked that way, though. Wealth accumulates through grassroots sales. For most musicians, with the exception of say, people like Soulja Boy and Nickelback, popularity is a validation of artistic merit. And since Swift sells by volume more singles and albums than 99.999 percent of her peers, surely she doesn't mean that popular music can't also be art; that would mean that her life work she so passionately defended her right to sell isn't actually art. And if her music isn't art, then it's not valuable and not worthy of purchase.

But she has a point -- rare is valuable. Before Napster and CD burners, music was indeed rare. The record industry held a monopoly on supply, allowing them to set the price as they saw fit, and people willingly paid it. These days, though, the supply of music is unlimited. File-sharing and Youtube make music free and infinite, and consumers have practically re-classified the act of paying for music as philanthropy.

And of course, in the battle between the $10 album and the $0 album, the latter always wins.

This is why Wu-Tang's single album ploy is so brilliant. It flips the script on its head; it both controls supply and generates intense demand. When Wu-Tang's lackluster twentieth anniversary album quietly dropped last month, you could hear crickets around the rap world. When the needle for Once Upon a Time in Shaolin moves just slightly as it did last week (the announcement was really just a slight change in how the group planned to sell the album), a whole world outside of hip-hop pays attention.

All musicians today must confront the idea of scarcity. When no one wants to pay for your art, you must find other ways to make your work attractive. Musicians are told to do this these days by pouring energy into improving the live show (music supporting entertainment) or by selling merch (music supporting commerce). Once Upon a Time in Shaolin proves that artists aren't bound to the dominant narrative, and that the world will reward outside-the-box solutions to common problems.

RFT MUSIC'S GREATEST HITS

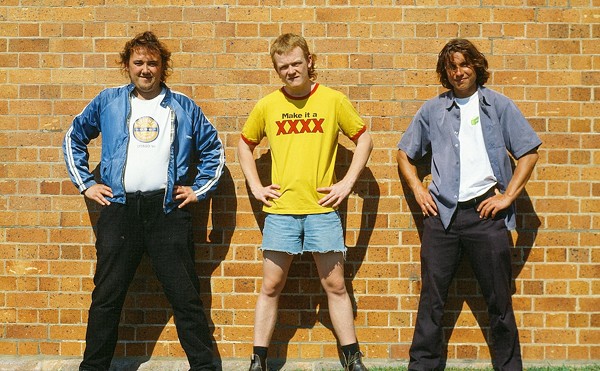

The 15 Most Ridiculous Band Promo Photos Ever "Where Did My Dick Go?" The Gathering of the Juggalos' Best Overheard Quotations I Pissed Off Megadeth This Week, My (Former) Favorite Band The Top Ten Ways to Piss Off Your Bartender at a Music Venue

Follow @rftmusic